Grazyna Kulczyk’s collection on show at Boadilla del Monte, Madrid

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The Polish millionaire, savvy investor and art lover Grazyna Kulczyk – tiny, birdlike, perched on high heels, with her blond hair in a neat bob – was in Spain on Valentine’s day, solicitously taking guests around the first exhibition of her collection to be held outside her native Poland. The setting was the Santander Art Gallery, where the bank, through its foundation, has an arts programme that spans Hieronymus Bosch and Goya and collections of contemporary art.

Previous shows in the space have featured the Italian Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, American Rubell and British Cranford collections, which were also shown in Santander’s HQ, a spaceship-like building in its Financial City outside Madrid. This year the spotlight is falling on Kulczyk, Poland’s richest woman, its leading collector and also a proficient businesswoman and investor who has long seen the benefits of linking art with commerce.

Curated by Timothy Parsons, the exhibition, Everybody is Nobody for Somebody, draws on her holdings of Polish art from 1945 to 1989, and juxtaposes them with works she has bought by western artists – among them Richard Buckminster Fuller, Olafur Eliasson, Donald Judd, Gabriel Orozco and Jenny Holzer.

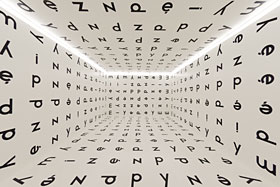

The surprise is how relevant the Polish artists’ work appears, despite their political isolation during the communist period. One room confronts Judd and Flavin with the avant-garde Stanislaw Drózdz, whose 1977 “Between” is a room lined with letters. A large section devoted to female artists features Alina Szapocznikow, whose 1970s works evoke both Louise Bourgeois and Berlinde de Bruyckere; other works in this section are by Agnes Martin, Valie Export and Rosemarie Trockel.

Recent acquisitions in the show include a Joan Mitchell from 1965 and Teresa Tyszkiewicz’s boldly coloured abstract “Composition” from 1959. Also on show are works that are significant in Poland’s tragic history in the 20th century: Andrzej Wróblewski’s “Mother with a Killed Child” (1949) and Wladyslaw Strzeminski’s 1948-49 “Composition”. Like many artists, Strzeminski was accused of “formalism” during the Stalinist period and died in poverty after being sacked from the academy in Lódz.

We meet the following day in Kulczyk’s hotel, where, clad in jeans and a cashmere sweater, she tells me how she came to build up what is now acknowledged as Poland’s most important collection of contemporary work.

A self-proclaimed perfectionist, she methodically outlines to me her involvement with art, starting with her law degree in her home town of Poznan in the 1970s. “Poznan was very vibrant culturally at the time,” she says. “In a paradoxical way, the unfree society was inspiring for artists – they had to work in a hidden way that the authorities completely failed to understand.”

There was an explosion in graphic design, and Kulczyk’s first purchases were posters; she was also “earning extra money”, she says, by travelling to various government-established “culture houses” to lecture about young Polish artists. And while a free art market did not really exist, there were a few private galleries: “But most people went directly to the artists,” Kulczyk says. “The environment was so closed at that time, no one even thought that communism would fall, so the perspective was purely Polish art and artists.”

Is collecting art as profitable as it is painted?

A new book challenges the notion that art is an investment-grade asset

After her marriage to industrialist Jan Kulczyk, now Poland’s richest man, she worked in his businesses, post-communism: car dealerships, telecoms and energy. She started collecting “the art that was offered by the market at that time, the art one was supposed to have,” citing Tadeusz Kantor or the revered 19th-century painter Jacek Malczewski.

“After the political system changed, I realised that artists had to make a living and, as we had car showrooms for Audi and Volkswagen, I put work by Polish artists in them. I even offered works along with the cars sometimes, and then sent the artists the money,” says Kulczyk. She also started buying art for her own company, a Skoda dealership: “People appreciated seeing the art, and recognised that it played an important role in the working environment.”

But her most prominent venture was the purchase of Stary Browar, a former brewery, in 2003. The sale was not without controversy: Poznan’s mayor, Ryszard Grobelny, was initially accused of incurring a loss to the city of 7m zlotys (about $2.3m) by selling too cheaply. Kulczyk has now made available to the city the four-hectare park surrounding the brewery.

“When I bought Stary Browar, it was totally dilapidated,” she says. “At first I offered it to artists, performers, dancers, to do what they wanted, for free. But this ‘romantic’ initiative couldn’t last; the building wasn’t usable in winter, so I realised I had to reorganise it along business lines.” This is how her 50:50 scheme was born: the building was regenerated with shops and restaurants put in alongside free-entry non-profit art galleries and performing arts spaces. The idea is that the commercial side funds the artistic side: in 2008 it won a European Shopping Centre award.

By the early years of this century, Kulczyk had moved on to buying international artists: her first purchases were two Warhol silkscreens in 2002, as well as a Tapiès in 2003; initially she also bought photography. While there is no curator of the collection as such, New York-based art historian Paulina Kolczynska, whom she met in 2007, serves as consultant.

Kulczyk will not talk about her 2005 divorce, but in the settlement she reportedly received all of her husband’s domestic businesses, and has fructified this – she was listed in the Polish magazine Wprost as being worth 2.4bn zlotys (about $790m) last year. Her investments are mainly in real estate, including in the UK, and new technologies.

A big disappointment, however, was her ambitious plan to build an art museum in the park surrounding the brewery. “I went to Osaka to meet Tadao Ando; I saw some other of his buildings in Japan – for instance Naoshima,” she says. “It was like a dream. Tadao came to Poznan, he wanted to design a building completely underground, going down 12 or 13 metres, with a Turrell room . . . but when I presented the project to the local authorities, they said they had no money for it: I would have paid for the building and the collection, but I wanted them to pay for the upkeep, to make it sustainable in the future.”

The result is that the museum will not happen; Kulczyk has now bought another brewery, this time in Switzerland, close to St Moritz. “I plan to show Polish artists there,” she says.

She is also on the acquisition committee at Tate for Russian and eastern European art, but one senses that Polish artists are particularly close to her heart. “I see myself as an ambassador for contemporary Polish art,” she says. I ask her if she thinks of the collection as an investment. “Of course!” she replies. “It’s an investment, but it is not for sale; it’s for the Polish people.”

‘Everybody is Nobody for Somebody’, Boadilla del Monte, Madrid, to June 15

Comments