Lunch with the FT: Dana White

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The day after my lunch with Dana White, the two of us meet again. This time it is not around a table in a Mayfair restaurant but around a cage in which two half-naked men are beating the hell out of each other.

It is the Ultimate Fighting Championship fight night at the O2 Arena in London and White, who has made cage fighting into one of the fastest- growing sports in the world, has invited me to watch it with him. He’s also asked a curious assortment of celebrities, including Damien Hirst, Guy Ritchie, and Niall Horan from One Direction, who is excitedly tweeting: “Jesus Christ that was unbelievable! …Some serious brawls!”

I’m finding the spectacle perplexing. UFC, aka mixed martial arts (MMA), is made up of so many different sports – including kick-boxing, jiu jitsu, wrestling, karate, sambo – it’s hard to work out what’s going on. But the 15,000 young City types who have paid an average of £200 a ticket appear unbothered by the niceties of this human chess game. Instead, they roar with delight at every sickening thwack of thinly gloved fist on flesh, booing every time the blows abate. The only person in the packed arena who appears unmoved is the rapper Dizzee Rascal, who looks bored rigid.

This baying for blood is far more disturbing than the blood itself, which is in relatively short supply. Yet more disturbing than either is my own behaviour. At first I simply wish the pummelling would stop but, after a couple of hours, I’m out of my seat, arms punching the air and I’m bellowing at an underdog who has just staggered to his feet: “Hit him!”

….

The previous day I arrive first for lunch at C London, the Mayfair sister restaurant of Harry’s Bar in Venice. After a longish wait, during which a stream of men in elegant tailoring are shown to their tables, the revolving door spits out a man of substantial bulk with a shaved head. The maître d’ clasps him to his own substantial breast and points him towards me.

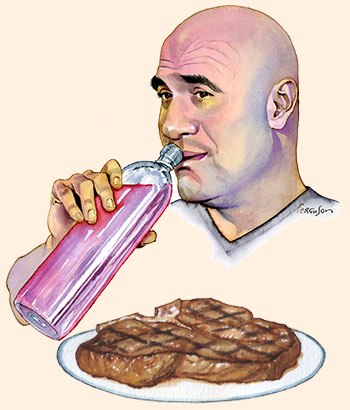

Dana White swaggers over, wearing jeans and a tight black V-neck that draws attention to the heft of the muscles underneath and makes one wonder if he really needs the human hulk of a bodyguard, who trails behind him and sits at the next table. The UFC president extends one hand to shake mine; with the other he is clutching a half-empty bottle of pink liquid that he keeps swigging from. It is bad manners to bring your own drink to a smart restaurant but the maître d’ asks unctuously what is in the bottle and is told it is half-water and half-vitamin water. “I’m a weirdo,” White declares, as if charmed by his own eccentricity.

Before he has even sat down, the two men start a lively discussion about meat. My guest says he wants his usual, a rib-eye steak; the maître d’ sings the praises of a veal chop and White says he’ll have that as well, on the side. He orders two starters and then settles into his seat.

I begin with a few preliminaries: What does he like about London? “Harvey Nichols is a blast.” He also likes the restaurants. “This place is insane.” Such talk does not detain us long, as what I really want to know about is one of the least probable transformations in sporting history.

In 2001, White, then a college dropout of barely 30 who had been earning a living as a boxing trainer, bellboy and bouncer, got in touch with his wealthy school friend Lorenzo Fertitta, heir to a Las Vegas casino empire. He suggested Lorenzo and his brother Frank spend $2m on a nearly bankrupt, thoroughly disreputable UFC and install him as president; far from telling him to get lost, the two readily agreed.

Thirteen years later, the sport is edging towards the mainstream in the US and is now going global. Young, affluent, blood-loving men in Canada, Brazil, Europe, Australia, UAE and China can’t, it seems, get enough of it.

I say that it is odd, at a time when we are obsessed with safety, political correctness and emotional intelligence, that such an unashamedly violent sport should be so popular. White leans forward in his chair.

“I don’t care what colour you are, I don’t care what country you’re from. We’re all human beings, fighting’s in our DNA. We get it. And we like it.” His tone is even, his smooth face impassive. But there is a tension in the 44-year-old’s Boston accent that makes me edgy. This could go wrong at any minute.

I protest that fighting isn’t in my DNA (an idea I am to be partly disabused of the following day) and that I neither like it nor get it. He shakes his head and gives a smile made more threatening by its sweetness. “England has been kicking ass since the beginning of time. Fighting is in your DNA.”

But surely kicking ass is a low side of human nature that we ought not to encourage? Again he smiles at me, as if I’m a slow child.

“The most famous athletes throughout the history of time are fighters. Now, I don’t know any of your soccer players or any cricket guys but I bet you’ve heard of Muhammad Ali.”

So we start a slightly pointless exchange in which I ask if he’s heard of David Beckham, Ian Botham or Kevin Pietersen (yes, no, no) and he asks if I’ve heard of Bruce Lee and Manny Pacquiao (yes, no). This is diverting but it does not establish whether it is morally OK to enjoy watching two men beating each other to a pulp.

“When you get two athletes and they’ve been training their whole life to see who’s the best in the world, you should absolutely enjoy that. I love every style of fighting – and, yes, if a fight broke out here, I’d watch that too.”

He casts a slightly wistful look into the peaceful Mayfair street outside.

….

The starters arrive and I rather regret my choice of octopus and celery salad, arranged in a lumpy pastel puddle. White tackles his first starter, meticulously separating the beetroot from the asparagus and goat’s cheese (“I’m not a beets man”).

As he does so, I try to get him to give me a tutorial on the economics of cage fighting. The top three fighters, he says, have made fortunes of $30m dollars or more, though how much the junior ones make, he won’t say. (I later discover they get a mere $6,000 for being beaten up; double that if it is they who has done the beating.)

“We don’t let the media know a lot of the numbers. It pisses them off,” White declares, finishing one starter and moving on to the next. He tells me that the biggest source of revenue for UFC is pay-per-view TV – the most popular fights are watched by 1m people paying $50 each – but refuses to say anything more.

Using the oldest trick in the journalist’s book, I drop into the conversation a figure of $1bn, which was what the New York Times estimated the business was worth a couple of years ago. Is that number still correct?

White chews on a slab of mozzarella taken from his second starter and says nothing at all. Then he whispers, “$3.5bn. Some would say more.”

I ask how he reached that number and he replies, mysteriously, “We have numbers. You know what I mean?”

Yet in the US his critics claim growth has stalled, with fewer fans tuning in to watch fights. Two of the biggest champions – Georges St-Pierre and Anderson Silva – are not currently fighting, the latter having broken his leg in a fight that can be seen in gory slow motion on YouTube, his shin bone bent in half like a piece of rubber.

“I’ve been listening to people tell me that we we’re going to fail for 13 years. The media is full of shit. The company grows bigger every year.”

Both those stars are coming back, he insists, and reels off a list of other fighters. And it’s not just men, women now fight too. “Have you heard of Ronda Rousey?” he asks.

On his phone he shows me a clip of the bantamweight champion. She is all bikini and muscles and highlighted hair topped with the scariest pout I’ve ever seen on a woman. She’s been particularly big on the smash hit reality TV show The Ultimate Fighter, a sort of Pop Idol with punching.

“She’s a rock star, man,” he says. “The women are different than the men – way more emotional. They’re a lot more catty. I’ve been trying to figure out women my whole life and now I’m trying to figure them out on a different level.”

Two vast plates of meat have arrived for him, against which my fillet of bream looks laughably wimpish. As he starts on the veal chop, I work out that only 16 hours have passed since his last meat feast. The previous night he had posted pictures on Twitter of the vast curry he was eating, causing many of his 2.8m followers to retweet the picture or speculate over what it would do to his digestive system.

“Isn’t social networking great?” he says. “It’s such a great way of talking to fans. If I sent a tweet out right now and said, ‘I’m at C, Cipriani’s,’ it would be a fucking mad house.”

I am slightly sceptical about his pulling power in Mayfair and beg him to try it but he refuses. Instead, he busies himself with his meat, deftly slicing off the brown outside bits and eating only the meat in the middle.

Though fans love him, they don’t do so uncritically. He got a lot of stick last year when Georges St- Pierre, face mashed up and barely making sense after a fight, said on TV that he needed a break. At a press conference, White said the champion couldn’t have one. When I ask if he regrets being so unfeeling, he shrugs.

“That wasn’t about what you thought it was about. Here’s the bottom line; I’m never going to be the good guy, no matter what I do or what I say. I run a company with 500 of the baddest dudes in the world and I am the boss.”

Are bad dudes harder to manage than the norm? “Nah. They’ve got smaller egos than journalists. They are smart guys. And some of them are smarter than me!” I laugh, thinking he’s made a self-deprecating joke but then, seeing his expression, stop at once.

Our plates are cleared. His is a large pile of bits he has cut off two slabs of meat. The vegetables are taken away untouched.

I wonder if White fears that one day MMA will be deemed too dangerous and made illegal. “Nothing shocks me but that would be crazy. You wanna stop people hurting themselves? Let’s get rid of fucking cigarettes first, OK?”

For now he is keen to stress how safe the sport is. There are lots of strict rules: no biting, no eye-gouging, hair-pulling, headbutting, fish-hooking or kicking in the groin. In its 20- year history no one has died. “Not many sports can say that, not even cheerleading can say that.”

I point out that, as the sport is so young, we don’t yet know what long-term damage it does. “Yes, we do,” he insists. “No one ever said being punched in the head is good for you. We spend a lot of money on research for brain injuries. They’re starting to think there’s a gene in people that means you’re more susceptible to having brain injury than others. Isn’t that interesting?”

I order coffee while White sticks with the pink stuff. Our talk shifts to the future and I ask if the Fertitta brothers might one day sell up.

“Maybe,” he says, which isn’t the answer I’d expected. “At the end of the day we’re all young guys.” But for now the three of them love working together. Their secret? “No ego. People don’t believe that about me but I’m completely ego-free.”

As this is not the popular view of White, I ask him to explain. “I’ll tell you this. How many times do you think I’ve been offered to write a book? Big money. Three million. One time I sat down and I said, ‘I’m going to do it.’ But I got so fucking sick of talking about myself, by day two, I was done.”

While White has refrained from writing about himself, his mother, who brought him up alone, has been more forthcoming. In 2011 she published an unauthorised biography of her son in which she said power and money had made him “egotistical, self-centred, arrogant and cruel”.

I drop the name of June White with some trepidation, expecting one of his frightening smiles. Instead, he looks unconcerned. “I have no relationship whatsoever with my mother and haven’t for a long time,” he says evenly.

But is she right that power and money and success have changed him? “I’m nice to everybody, I respect other people. If you respect me, I respect you. But if you don’t …”

He tails off. Then what?

“Well, I’ll give you an example; it’s one of the problems I have with Twitter. Let me show you. This is from earlier today. Some English guy was saying all kinds of rude shit.” He shows me a tweet that reads “@danawhite knacker sack head”. To this he proudly lets me read his reply: “Have no clue what that means but fuck u too.”

I suggest that it might have been wiser to let that sort of thing go, and he looks at me pityingly. “If somebody said, ‘I know you write for the Financial Times, not only do you suck, everything you do is a piece of shit and . . . I don’t like your hair either.’ What would you do?”

The UFC president’s pugnacious charms have been an asset to the sport in its young days but I wonder if, as the sport grows up, something more corporate might be called for. White glowers at the thought.

“People have been asking me that since 2004. The answer is it’s 2014 and I’m still here. Am I a little rough around the edges? Do I say things that people don’t like sometimes? Do I swear a lot? Yes, yes, yes. Life’s hard, man. If you can’t handle a couple of curse words, you’ve got bigger problems than me personally. Right?”

It is time to stop. White needs to watch the fighters weigh in before the following day’s action. “I fucking love the weigh-in, man,” he says, getting up. “I’m gonna use the rest room real quick, right?” As he goes he hands his credit card to a member of staff. I get up and tell the bodyguard that the FT is paying for our meal. A look of fear crosses his face. No, it can’t be done: Dana won’t like it.

When White returns I find myself apologising for having bought him lunch and, for a second, fear an explosion. But then he says: “I understand. An absolute pleasure, sweetheart.”

Lucy Kellaway is an FT columnist

——————————————-

C London

23-25 Davies Street

London W1

San Benedetto water £5.50

Octopus and scampi £22.70

Asparagus salad £19.50

Buffalo mozzarella £18.90

Sea bream £33.60

Veal chop £40.90

Scottish rib-eye steak £41.50

Coke £5.50

Double espresso £3.70

Total (incl service) £220.57

——————————————-

Special Event

Literary Lunch with the FT

On Saturday March 22 at the FT Weekend Oxford Literary Festival, Lucy Kellaway joins FT editor Lionel Barber and Caroline Daniel, FT Weekend editor, to discuss what makes a classic Lunch with the FT. For tickets and details of the event, which includes lunch, visit oxfordliteraryfestival.org

Comments