Activist who fled jail in Benin to become a Princeton professor

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In 1986, Leonard Wantchekon, then a student leader in Benin, west Africa, escaped from Segbana jail after being tortured and held for 18 months for organising university protests against the dictator Mathieu Kérékou. “I escaped and made it across the border to Nigeria, then the Ivory Coast, and a year later to Canada,” says Wantchekon. “I was a political refugee, without a home country.”

Now a professor of politics at Princeton University in the US, he reflects on the long journey he took, from a dank prison cell to one of America’s top universities.

Outside, it is a cold and drizzly autumn afternoon and red maple leaves paper the pavement. Inside the 1970s-style duplex, which Wantchekon, 57, shares with his wife, Catherine, a university financial manager, the rooms are decorated in calm, neutral colours and are filled with artefacts and family photographs.

He has just one complaint: “It’s too quiet for me – I like student energy on campus.” Even on football weekends? (Princeton’s football stadium is visible directly across from the house) “American football is surprisingly quiet,” he says.

Although he teaches full-time at Princeton, Wantchekon has recently embarked on a parallel mission in his native Benin: to create a first-rate university from scratch, complete with a new campus. Named the African School of Economics (ASE), it has grown out of a research institute that Wantchekon founded in Benin in 2004. ASE, which will partner with Princeton, will officially open in the autumn of 2014. “We’ll start with 300 graduate students and rent a location while we build the new campus,” he says.

At home in Princeton, Wantchekon has turned his window desk, with its neat piles of papers, into a virtual planning site. “This house is five minutes from my office. But when I’m home, I’m on Skype two to three hours a day with colleagues in Benin. This is where I sit, think and work.” He opens his laptop to show off architectural designs for striking concrete and glass-sided buildings. Time is also being spent devising courses. “Mathematics and statistics will be the core,” he says.

A top maths student himself, Wantchekon began organising protests while still at school. “I became a pro-democracy leader,” he says. And his activism got him expelled from the National University of Benin in 1979. “I lived in hiding, organising students, writing for the underground newspaper.” During a brief amnesty in 1985, he re-enrolled as a student only to mobilise a larger protest and the rallies that led to his arrest.

It was only after he had settled in Canada that Wantchekon finished his degree, before moving to Northwestern University in Illinois, where he completed a PhD in economics. Then in 1995, he was hired by Yale and, after a stint at New York University, he accepted the post at Princeton in 2011.

Wantchekon’s attention turns to objects in his sitting room. “I bought this in Cotonou,” he says, pointing to an African mask on the wall. “It’s an ancestor’s mask. You have street vendors who sell you masks and they’re very, very talented,” he says, adding that, although not religious, the masks are thought to protect the home. “Masks are believed to capture the spirit of the ancestor looking out for us. They’re popular throughout Africa.”

On another wall hangs a colourful painting of a waterfall. “It’s a watercolour from South Africa,” he says, “but I think of this [simply] as an African landscape.”

The idea of a pan-African identity, a concept that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s during the struggle for African independence, has inspired Wantchekon’s vision for ASE. “We will draw the best students from across Africa and teach them to become future economists, political leaders, CEOs,” he says. “The research centres are [already] open. We have one masters programme in economics and statistics. Next year, we’ll be upgrading to economics, mathematics and statistics, then we’re adding an MBA [and] an MPA.” A humanities programme, he says, “is on the books for 2016”.

So how does he respond to those who, citing trade restrictions and regional instability, among other issues, dismiss the notion of an African identity? “I strongly disagree,” says Wantchekon. “In academia, there are more pan-African institutions than ever: African Economic Research Consortium, Afrobarometer, African University of Science and Technology,” he says. “And now our applicants are coming in from 25 African countries.

Wantchekon envisages a future Africa of tightening economic and political integration along the lines of the EU. “Market fragmentation is inefficient, [it] reinforces division and [allows] limited development . . . “Eventually, we need an African central bank,” he says. “Francophone countries have their central banks based in Dakar and Yaoundé and they’re still led by the Banque de France. Former British colonies have their central banks.”

His hope is that ASE will help to sow democracy across the region. His own Benin-based research, published in the October issue of the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, compares town hall meetings with rallies in campaigns. “We’ve found that town hall meetings are much more effective in reinforcing issue-based voting.” Africa’s most valuable resource, he adds, is its young people. “We have a very young, dynamic, ambitious population. We just need to train them.”

Students from ASE have already impressed their counterparts at Princeton. “I brought 14 grad students from Princeton to Benin and they realised some students there were even stronger. They didn’t expect that,” says Wantchekon.

Arranged on the shelves of a large bookcase to the right of the eating area are photos of his two grown-up children, Travis and Kristia. “I put pictures of my children everywhere. I have my son here playing football,” he says. Meanwhile, he credits Catherine for giving him balance. “I met her when I was running, in hiding. She isn’t an activist. She gave me a sense of reality,” he says. Still, Wantchekon sees building his school as an extension of his early struggle. “Now Benin is a democracy. But we fought for it. I remember when it seemed impossible.”

Wantchekon has secured the land for the ASE campus in the city of Akassato in southern Benin and is currently raising construction funds, but his plans will not stop there. “We’ll eventually have a museum of social history,” he says, “a botanical garden, even a football stadium.”

Continuing his tour of the house, Wantchekon walks out to a shared back terrace with iron-grate furniture. The couple have recently bought another house nearby, which they will co-own with the university. Wantchekon is looking forward to more space and says he is pleased they will remain close to the activity and bustle of student life, adding, “I get inspiration from my interactions on campus.”

This article has been amended since publication. In the original a quote stated that the central bank of francophone African countries is based in Dakar (Senegal). In fact there are two CFA Franc zone central banks, one in Dakar and one in Yaoundé (Cameroon).

——————————————-

Favourite Things

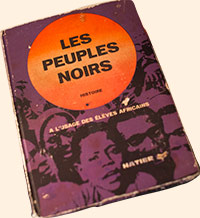

The first object Wantchekon selects is an old book from school. “I still have my sixth-grade African history book, Les Peuples Noirs,” he says, retrieving a tattered textbook from Benin. “It’s rigorous and nicely written,” he says, “I’m puzzled how, over four centuries of slave trade, African families and culture survived. You had migration, people permanently on the run to escape slave trade, war, disease. They didn’t have homes.” The second object is his certificate from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. “It was moving,” says Wantchekon, of his election in October as the first African economist voted into the academy. “I was touched by messages from across Africa: Cameroon, Mali, Congo, Malawi. I was congratulated not as a person from Benin, but as an African; for representing Africa.”

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

CFA Franc zone’s two central banks / From Mr K Felix Mjumbe

Comments