Inside China’s secret ‘magic weapon’ for worldwide influence

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

On the Google map of Beijing there is an empty quarter, an urban block next to the Communist party’s leadership compound in which few of the buildings are named. At street level, the aura of anonymity is confirmed. Uniformed guards stand by grand entrances checking official cars as they come and go. But there are no identifying signs; the sole information divulged is on brass plaques that bear the street name and building numbers.

The largest of these nameless compounds is 135 Fuyou Street, the offices of the United Front Work Department of the Chinese Communist party, known as United Front for short. This is the headquarters of China’s push for global “soft power”, a multi-faceted but largely confidential mission that Xi Jinping, China’s president who on Wednesday was confirmed in place until at least 2022, has elevated into one of the paramount objectives of his administration.

The building, which stretches for some 200m at street level, signifies the scale of China’s ambition. Winning “hearts and minds” at home and abroad through United Front work is crucial to realising the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people”, Mr Xi has said. Yet the type of power exercised by the cadres who work behind the neoclassical façade of 135 Fuyou Street is often anything but soft.

A Financial Times investigation into United Front operations in several countries shows a movement directed from the pinnacle of Chinese power to charm, co-opt or attack well-defined groups and individuals. Its broad aims are to win support for China’s political agenda, accumulate influence overseas and gather key information.

United Front declined interview requests for this article and its website yields only sparse insights. However, a teaching manual for its cadres, obtained by the Financial Times, sets out at length and in detail the organisation’s global mission in language that is intended both to beguile and intimidate.

It exhorts cadres to be gracious and inclusive as they try to “unite all forces that can be united” around the world. But it also instructs them to be ruthless by building an “iron Great Wall” against “enemy forces abroad” who are intent on splitting China’s territory or hobbling its development.

“Enemy forces abroad do not want to see China rise and many of them see our country as a potential threat and rival, so they use a thousand ploys and a hundred strategies to frustrate and repress us,” according to the book, titled the “China United Front Course Book”.

“The United Front . . . is a big magic weapon which can rid us of 10,000 problems in order to seize victory,” adds another passage in the book, which identifies its authors and editorial board as top-level United Front officials.

In a rare news conference this month, Zhang Yijiong, the executive vice-minister of United Front, said: “If the Chinese people want to be powerful and realise the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, then under the leadership of the Communist Party we need to fully and better understand the use of this ‘magic weapon’.” Sun Chunlan, the head of United Front, this week retained her position in the newly selected politburo.

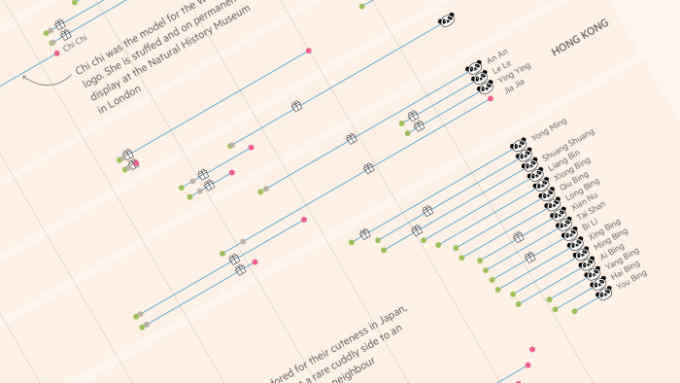

The organisation’s structure exhibits the extraordinary breadth of its remit. Its nine bureaux cover almost all of the areas in which the Communist party perceives threats to its power. The third bureau, for instance, is responsible for work in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and among about 60m overseas Chinese in more than 180 countries. The second bureau handles religion. The seventh and ninth are responsible respectively for Tibet and Xinjiang — two restive frontier areas that are home to Tibetan and Uighur minority nationalities.

Merriden Varrall, director at the Lowy Institute, an Australian think-tank, says that under Mr Xi there has been a distinct toughening in China’s soft power focus. The former emphasis on reassuring others that China’s rise will be peaceful is giving way to a more forceful line. “There has been a definite shift in emphasis since Xi Jinping took over,” says Ms Varrall. “There is still a sense that reassuring others is important, but there is also a sense that China must dictate how it’s perceived and that the world is biased against China.”

What the nine bureaux do

1. Parties work bureau The first bureau deals with China’s eight non-communist political parties and recommending their members for positions in the National People’s Congress [parliament] and other bodies. Though these parties have little or no power, they are seen as an important part of China’s political structure.

2. Minorities and religions bureau China has 55 official national minorities. United Front is charged with building coalitions of shared interests to ensure that distinct identities do not evolve into separatism. It is also charged with ensuring that all practising religions in China regard the Communist party as their highest authority.

3. Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and overseas liaison bureau Maintaining loyalty to the Communist party in Hong Kong and Macau is an important United Front function. Taiwan work focuses on building coalitions with those who identify with mainland China while seeking to undermine those that support the island’s independence. Cultivating loyalty among more than 60m overseas Chinese is seen as crucial to burnishing China’s reputation abroad.

4. Cadre bureau Little is known about the work of the fourth bureau, which focuses on cultivating cadres and operatives throughout the vast United Front system. The number of United Front officials and operatives is unclear, along with the organisation’s budget and spending patterns.

5. Economics bureau Works to cultivate loyalty among people and areas that have been left behind by the country’s economic advance. It plays an active role in poverty alleviation, especially in “old revolutionary base” areas such as in north-east China.

6. Non-party members, non-party intellectuals The sixth bureau is charged with cultivating support among intellectuals and other influential people who have no party affiliation in China.

7. Tibet China’s efforts to suppress separatism in Tibet and undermine the Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in northern India, is a key aspect of United Front Work. It also seeks to win hearts and minds around the world by stressing Beijing’s contributions to the economic development of Tibet and its preservation of the region’s cultural legacy.

8. New social classes work bureau The emergence of China’s vast middle class since the 1990s has created an influential group of people who have capitalist reforms to thank for their wealth and may thus feel little fealty to the Communist party. This bureau is dedicated to fostering unity among this group.

9. Xinjiang China’s vast north-west frontier region of Xinjiang is home to millions of Muslims that belong to minority nationalities such as Uighurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and Tajiks. This bureau is charged with cultivating loyalty and suppressing separatism among these minority peoples.

. . .

The hard edge of United Front is evident in its current struggle over the future reincarnation of the 14th Dalai Lama, the 82-year-old exiled Tibetan spiritual leader who Beijing castigates as a separatist bent on prising Tibet from Chinese control.

Tradition dictates that after a Dalai Lama dies, the high priesthood of Tibetan Lamaism searches for his reincarnation using a series of portents that lead them to his reborn soul in a child. The leaders of Tibetan Buddhism live in exile with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, northern India, raising the prospect that a reincarnation may be found somewhere beyond China’s borders.

Beijing is alarmed. The last thing it wants is for the man it has called a “splittist” and a “wolf in monk’s clothing” to be reincarnated in territory it does not control. United Front is charged with crafting a solution. The plan so far, officials said, is for the Communist party — which is officially atheist — to oversee a reincarnation search themselves within Chinese territory. Partly to this end, it has helped create a database of more than 1,300 officially approved “living Buddhas” inside Tibet who will be called on when the time comes to endorse Beijing’s choice.

“The reincarnation of all living Buddhas has to be approved by the Chinese central government,” says Renqingluobu, an ethnic Tibetan official and a leader of the Association for International Culture Exchange of Tibet, a United Front affiliate.

“If [the Dalai Lama] decides to find the reincarnation in a certain place outside of Tibet, then Tibetans will wonder what sort of reincarnation is this and the masses will think that religion must be false, empty and imaginary after all,” said Mr Renqingluobu on a recent visit to London.

The Tibetan government-in-exile criticises the “preposterous” plan, adding in a statement from Dharamsala: “If the Chinese truly believe that the 14th Dalai Lama [the current one] is a ‘leading separatist who is bent on destroying the unity of the motherland’, what is the point of looking for another one?”

Venturing into the realm of the metaphysical may appear counter-intuitive for atheist United Front operatives, but all of China’s national religious organisations come under the auspices of United Front work. These include the Buddhist Association of China, the Chinese Taoist Association, the Islamic Association of China, the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association and the Three-Self (Protestant) Patriotic Movement.

This portfolio means that United Front also leads China’s delicate talks to repair fractious relations with the Vatican, according to diplomats. The main sticking point is Beijing’s insistence that all religions in China must regard the Communist party as their highest authority — a position which in Catholicism is occupied by the Pope.

The two sides have been manoeuvring, mostly in secret, for more than a decade to find common ground. There have been signs of progress in recent years, with both sides agreeing to recognise the appointment of five new Chinese bishops in 2015 and 2016.

Nevertheless, officially at least, United Front remains resistant. “We must absolutely not allow any foreign religious group or individual to interfere in our country’s religions,” the United Front book says.

For Beijing, growing social diversity after nearly four decades of economic reform has emphasised United Front’s value in maintaining loyalty and support beyond the mainstream Communist faithful. Successive leaders have lauded United Front but none more so than Mr Xi, who made several moves in 2014 and 2015 to upgrade the status and power of the organisation.

Mr Xi has expanded the scope of United Front work, adding the ninth bureau for work in Xinjiang, meaning that the organisation now oversees China’s fierce struggle against separatism in the region. He also decreed the establishment of a Leading Small Group dedicated to United Front activity, signifying a direct line of command from the politburo to United Front.

But perhaps Mr Xi’s most important step to date has been to designate United Front as a movement for the “whole party”. This has meant a sharp increase since 2015 in the number of United Front assignees to posts at the top levels of party and state. Another consequence has been that almost all Chinese embassies now include staff formally tasked with United Front work, according to officials who declined to be identified.

This has given a boost to United Front efforts to woo overseas Chinese. Even though more than 80 per cent of around 60m overseas Chinese have taken on the citizenship of more than 180 host countries, they are still regarded as fertile ground by Beijing. “The unity of Chinese at home requires the unity of the sons and daughters of Chinese abroad,” says the teaching manual.

It recommends a number of ways in which United Front operatives should win support from overseas Chinese. Some are emotional, stressing “flesh and blood” ties to the motherland. Others are ideological, focusing on a common participation in the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people”. But mainly they are material, providing funding or other resources to selected overseas Chinese groups and individuals deemed valuable to Beijing’s cause.

One UK-based Chinese academic who has attended several United Front events describes how the experience begins with an invitation to a banquet or reception, usually from one of a host of “friendship associations” that work under the United Front banner, to celebrate dates in the Chinese calendar. Patriotic speeches set the mood as outstanding students — particularly scientists — are wooed to return to China with “sweeteners” in the form of scholarships and stipends, she adds. These stipends are funded by a number of United Front subsidiary organisations such as the China Overseas-Educated Scholars Development Foundation, according to foundation documents.

The largesse, however, may come with obligations. In Australia, the Chinese Students and Scholars Association acts to serve the political ends of the local Chinese embassy, according to Alex Joske and Wu Lebao, students at Australian National University. In one example, when Premier Li Keqiang visited Canberra this year, the CSSA fielded hundreds of Chinese students to drown out anti-China protesters on the street, Mr Joske and Mr Wu wrote in a blog.

To be clear, by no means do all Chinese students in Australia or elsewhere in the west see themselves as agents for soft power. However, Chinese and Australian academics have noted that pro-Beijing militancy is on the rise.

Feng Chongyi, professor at the University of Technology Sydney, says the influence exerted by Beijing over Chinese associations in Australia has grown appreciably since the late 1990s. “My assessment is that they control almost all the community associations and the majority of the Chinese-language media, and now they are entering the university sector,” says Prof Feng.

Away from such grassroots operations, a bigger prize is political influence in the west. The teaching manual notes approvingly the success of overseas Chinese candidates in elections in Toronto, Canada. In 2003, six were elected from 25 candidates but by 2006 the number jumped to 10 elected from among 44 candidates, it says.

“We should aim to work with those individuals and groups that are at a relatively high level, operate within the mainstream of society and have prospects for advancement,” it says.

At times, however, the quest for political influence can go awry. New Zealand’s national intelligence agency has investigated a China-born member of parliament, Jian Yang, in connection with a decade and a half he spent at leading Chinese military colleges.

A United Front operative since 1994, Mr Yang spent more than 10 years training and teaching at elite facilities including China’s top linguistics academy for military intelligence officers, the Financial Times learnt. Between 2014 and 2016 he served on the New Zealand government’s select committee for foreign affairs, defence and trade.

Anne-Marie Brady, a professor at New Zealand’s University of Canterbury, has said China’s growing political influence should be taken seriously. Noting that Canberra is planning to introduce a law against foreign interference activities, she also called for Wellington to launch a commission to investigate Chinese political lobbying.

In 2010 the director of Canada’s national intelligence agency warned that several Canadian provincial cabinet ministers and government employees were “agents of influence” for foreign countries, particularly China. In recent months, Australia has said it is concerned about Chinese intelligence operations and covert campaigns influencing the country’s politics.

But over time, such setbacks may prove temporary hiccups in the projection of China’s brand of hard-boiled soft power around the world.

“In the beginning the Chinese government talked about culture — Peking opera, acrobatics — as soft power,” says Li Xiguang, a head of Tsinghua University’s International Center for Communication Studies. “When Xi Jinping came to power, he was totally different from previous leaders. He said China should have full self-confidence in our culture, development road, political system and theory.”

Mr Xi’s elevation of United Front’s importance and power suggests that Beijing may be unwilling to tone down its efforts.

Additional reporting by Tom Mitchell

Comments