My father, the pioneer of sound design

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

My father, Errol Michael Henry, is an audio geek. He collects headphones and speakers in the same way some people hoard classic cars or stamps. To him, they are not only tools of his trade but works of art. Sound design determines the vibe and feel of an environment yet remains the unsung hero of the design world. Throughout his career as a producer, my father has worked for some luminary musicians and singers – Lulu, The Jones Girls, Jaki Graham and Bobby Womack – and helped define the sound of British culture. Much of his passion, his professionalism and his genius for sound have rubbed off on me. But while I could give you a guided tour of popular speaker brands, I couldn’t tell you how many black designers feature in the history of audio innovation.

My father grew up in a working-class Jamaican family in 1970s south London – at a time when it was frowned upon for the children of the Windrush Generation to have career aspirations beyond that of doctor or lawyer. “You could say my career in sound design began aged five, banging old boxes in my parents’ garden in Lewisham,” he tells me. “I was free to explore nature, and I discovered that in the rain, when I moved for shelter under the trees, the raindrops running off the leaves altered the acoustics of those sounds. In a way, banging boxes took me from Lewisham to LA where I ended up working as a music producer.”

My father’s schoolfriend, the actor Patrick Robinson, remembers him as constantly busy: “He was always designing things out of the stuff people threw away and his bedroom transformed into a makeshift lab with soldering irons, resistors, circuits and drawings,” he says, recalling how his friend’s passion for music was also evident early on. “I went to Lucas Vale Primary School aged eight and joined the school band – your father played the guitar and he was the lead singer. He taught me how to play the drums so that I could be a part of it all and make friends. We were called The Sparkles.”

It was a music teacher, Mr Smith, who first encouraged my father as a musical prodigy – a rare example of those pioneering educators who went against the prevailing racism of the era to give young black boys a sense of belonging. Smith took the band on a trip to a recording studio in London to make a school album. “All I remember is being nine years old, and walking into that control room and seeing the console,” says my father, who claims to have totally forgotten about making an album. “I thought I’d walked into the Starship Enterprise. Once I met the engineers and saw the tech, I just knew that was what I wanted to do and where I needed to be.”

At 11, my father had turned down a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music because the examiner had made a throwaway comment about “straightening out his unorthodox sound”. “I knew very early on that developing my own sound was part of my identity,” he says. “When my older brothers were out at work, I would take their speakers apart and put them back together before they came home, or play their records with my head between the speakers trying to imagine what and who was responsible for those sounds – and how I would play it differently.”

Super sonics: four legendary black producers

Quincy Jones

The African-American producer, arranger, composer and musician has helped define American pop for more than 70 years. His discography is vast and eclectic, spanning icons such as Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson and George Benson. In 2013, he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis

The African-American R&B/pop songwriting and record-production duo are widely recognised for crafting the Minneapolis Sound along with Prince. To date, they have received five Grammys and are among the few artists to have written and produced hits in three consecutive decades, from 1980 to 2000.

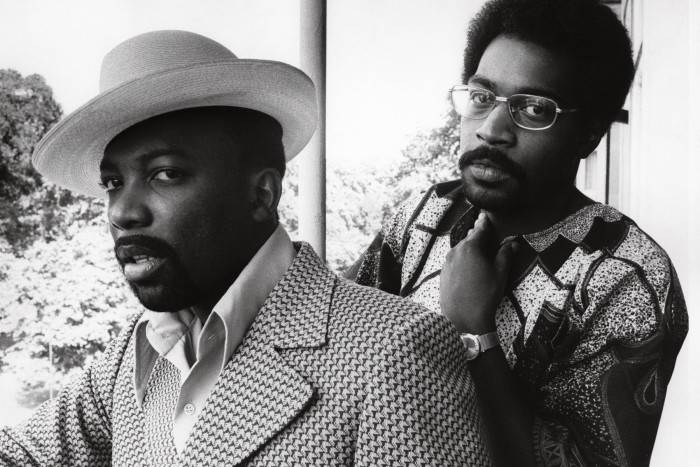

Gamble & Huff

The production and songwriting team of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff pioneered the Sound of Philadelphia – a genre of soul popular in the 1970s. Working with artists such as Teddy Pendergrass, The Jones Girls and Billy Paul, Gamble & Huff developed both a sound and a brand to rival Motown.

Nile Rodgers

The producer, songwriter and musician is famous for his “chucking” guitar style. As well as co-founding Chic, Rodgers has worked with artists from Sister Sledge to David Bowie, Duran Duran to Madonna. He has written, produced and performed on albums that have sold more than 500mn copies worldwide.

Fixed on a path, my father set about getting a job in sound design. He began working for Videotone, first on weekends aged 15, and later full-time. It was there he contributed to the history of audio innovation by creating the prototype Minimax 2 Speaker. “The bookshelf speaker was already a well established thing, but the ported bookshelf speaker [which has a hole or holes in the box fitted with a tube tuned to equalise pressure between the inside and outside] is another matter,” he tells me. “I was one of the first to use this method in such a small enclosure, and all the so-called experts assured me that my design would not work.” It did. “And not only that,” he adds, “but we developed innovative techniques to facilitate its manufacture.”

By the early 1980s, my father had become a session player, which quickly led to a new venture as a mixing engineer at Addis Ababa Studios in west London. The studio was an incubator for the underground British-Caribbean sound, and he worked alongside artists such as Jazzie B and Soul II Soul. “There was an underground jazz-funk fusion happening in the US during the ’70s, but by the ’80s a new wave emerged with a peculiarly British slant,” says Tony Monson, DJ and founder of Solar Radio. “We could always identify your father’s work by his sound, it was unique,” he says. “While he never attained the fame he should have done, he is one of the unsung pioneers of the British sound that emerged as a cultural response to the music scene in the US.”

“Your father had developed his own sophisticated soulful sound: it wasn’t ‘street’ – it was unorthodox,” agrees Peter Robinson, former head of A&R at RCA and founder of Dome Records, who commissioned my father to produce six tracks for Lulu’s 1993 album Independence. “The way he engineered the sound and built the tracks to sit alongside a clean groove – no one else was doing it in the UK at the time, and the sound your father designed to sit behind Lulu’s vocal was part of her successful commercial comeback.”

My father went on to work with EMI, Parlophone, BMG, Atlantic Records and Warner Chappell Music. By establishing his own brand – Intimate Records, Intimate Studios and Intimate Music Publishing – he was able to develop his own style of production, one born out of sound design. “Without people like Tony Monson and Peter Robinson operating as cultural curators, people like me remain unheard of,” he says.

Understanding the importance of mentors has led my father to devote the rest of his career to supporting the next generation of creatives. “I teach young mixing engineers that sound design is an art form but also a service. We are there to facilitate a performance, create space for expression and amplify experience,” he says. “To do that, you have to design a soundscape that has depth, texture and range that can be felt by the consumer, whether they are listening through cheap headphones or luxury speakers.”

For a long time, I thought my father was an exception in the history of music. But recently I stumbled across the biography of Hedley Jones, the inventor of one of the first solid-body electric guitars and architect of the modern-day sound system. Jones was a Jamaican second world war veteran and former radar engineer in the RAF. He went on to become a self-taught product designer and entrepreneur. I was shocked by how many things they shared in common: both played the cello and spent their youth inventing and experimenting with sound.

How different my father’s experience might have been had he known of people like Jones, or had stories of black, Jamaican inventors been widely taught in the curriculum. The story of black design has until now been woefully under-represented. I hope that by shining a light on my dad, I’m changing the course of that history. In the meantime, I sent my father a link to an article about Jones with the note: “You see! Sound design is a part of our culture!”

Comments