China’s migrants thrive in Spain’s financial crisis

Simply sign up to the European companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

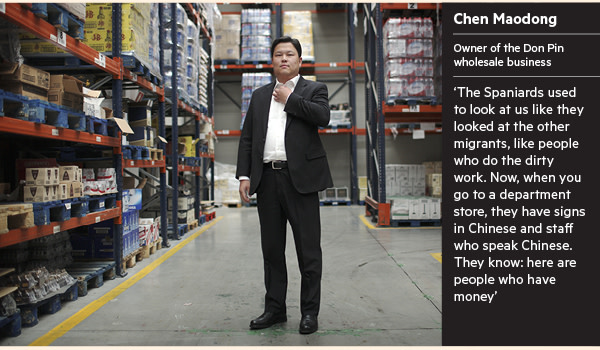

Laden with beer, liquor, soft drinks and snacks, the trucks are on their way to restock the thousands of Chinese-run corner shops and convenience stores that dot the Spanish capital. Business is good. It always has been, even in the worst moments of Spain’s economic crisis. Since 2008, the country has been through a housing bust, a banking crisis and a double-dip recession. But Don Pin, the wholesale company founded by Mr Chen, managed to triple its sales over the same time period.

With economic success has come a change in status for Mr Chen and for the Chinese community at large. “The Spaniards used to look at us like they looked at the other migrants, like people who do the dirty work. Now, when you go to a department store they have signs in Chinese, and staff who speak Chinese. They know: ‘Here are people who have money’.”

The bonfire of bankruptcies that burnt its way through corporate Spain during the downturn left the Chinese largely untouched – a result of hard work, thriftiness, luck and a business culture that values long-term survival above quick profits. “In China, we believe that the key issue is not whether you lose money or not, but whether you manage to hold on. So the Chinese have developed a great ability to withstand a crisis. You have to endure,” says Marco Wang, a businessman in Madrid whose assets include Spain’s leading Chinese newspapers.

The Financial Times this week is examining the modern trail of Chinese investment, migration and ambition in Europe. Still only 34 years old, Mr Chen has emerged as one of the most recognisable faces of the Chinese community in Spain – and as a symbol of its commercial clout and remarkable ability to withstand economic adversity.

His story finds parallels across the crisis-scarred countries in southern Europe, which have seen a burst in Chinese migrant arrivals – and in Chinese economic activity – despite the brutal recession of recent years.

Over the past decade, the number of Chinese arrivals in countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal has soared. According to official data, there are now more than 180,000 Chinese nationals living in Spain, three times more than in 2003. Add in students and naturalised Chinese, and the figure leaps to more than 200,000, the fifth-largest minority in the country.

Chinese migration to Spain continued to rise even after the start of the crisis, highlighting how well the community has been able to weather the economic storm. In a country where one-in-four workers is out of a job, unemployment is virtually unknown among the Chinese. Furthermore, they account for a vastly disproportionate share of business start-ups: there are now more than 40,000 self-employed Chinese on Spain’s commercial register, twice as many as before the crisis.

At the same time, there are growing signs that the Chinese are starting to work their way up the economic value chain. Gone are the days when Chinese economic activity in Spain was confined to serving up rollitos de primavera (spring rolls) or selling trinkets in dusty 100-pesetas shops. Today there are Chinese-owned fashion chains, import-export businesses, media groups and law firms. According to one estimate, the annual turnover of Chinese-run convenience stores alone amounts to €785m in total.

The community’s success has come, at least to European eyes, at a significant personal cost. Chinese shops stay open from morning until night, seven days a week, usually staffed by members of the same family.

Mr Chen says he has never taken a holiday. He returned to China for the first time 12 years after his arrival in Madrid, but is quick to stress that the trip was mainly for business. For most of his time in Spain, he spent money only on goods that he needed to make it through the day: “The moment you arrive in Spain as a migrant, you know that your mission is to earn money, not to enjoy life. You need a bed to sleep in and clothes to wear – nothing more. Later, when you have a business and things are going well you can allow yourself to buy something, but not before.”

He knows that such single-minded dedication to work is viewed by Spaniards (and much of the rest of the world) as an incomprehensible sacrifice. But Mr Chen has no doubt that it lies at the heart of his nation’s extraordinary economic rise. “It is with this sacrifice that China is conquering the world,” he says.

Dressed in a smartly cut black suit, white shirt and black tie, Mr Chen looks every inch the successful businessman. His replies are short and to the point, but he breaks into a wistful smile when he recalls how it all began. A native of Qingtian, an impoverished rural county in the coastal Chinese province of Zhejiang, he arrived in Madrid on November 10 1998. It is a date that is etched in his memory “like a second birthday”, he says. It was the first time he had left his home country.

The decision to depart had been, above all else, a family decision: his high school grades were not good enough to go to university, and earning money without a higher education would be tougher in China than in Europe. Besides, his older brother was already living in Madrid, part of a fast-growing migrant community from Mr Chen’s home region.

On the way from the airport, his first impression was that of a country not much richer than the one he was leaving behind: “The houses I saw along the way looked pretty bad. In China the houses are covered with tiles so they are pretty but here all you see are the bricks. I realised only later that Spaniards take greater care of the inside than the outside. Inside, their houses are always tidy, clean and pretty.”

Like most Chinese migrants in those years, he came without money and spoke no Spanish. Just 18, he earned his first cash waiting tables in a Chinese restaurant and selling plastic toys and cheap clothes at funfairs in villages across Spain. The only Spanish words he knew at the time were numbers (to haggle over prices) along with hola, gracias and adiós.

Determined to scrimp and save as much as possible, Mr Chen shared a single room with his brother, who had left the family home a few years earlier. “The only thing to do was to work, work, work. In the beginning, we didn’t even have a television. When we bought one, we bought a small one, so we could easily carry it with us when we had to move,” he recalls.

Four years after he arrived, Mr Chen joined forces with his brother and uncle to set up their own business. His partners had savings but they had to ask for loans from two other family members to reach the €20,000 they needed to buy their delivery van. “We worked every day from 8am in the morning to midnight. Once, I made a whole round trip just to take a kilo of peanuts to one of our customers,” he says.

The hard work paid off. As the number of Chinese-owned shops soared, so did the business of supplying them. Don Pin reported sales of €220,000 in its first year. Today it turns over more than €60m, boasts a fleet of 35 trucks and employs 110 workers.

Many of the men and women who work in the offices and warehouses of Don Pin come from the same tiny corner of China as Mr Chen himself. Most speak to each other in Mandarin but many conversations take place in the regional dialect spoken in Qingtian. This concentration highlights a crucial feature of the Chinese migration pattern – the influence of family and regional networks. The vast majority of Chinese living in Spain arrived here because a brother, cousin, husband or uncle made the same journey before.

Estimates vary but some believe that as many as 70 or 80 per cent of Chinese migrants in Spain come not just from the same province (Zheijiang) but from the same small county, Qingtian. Their dominance is reflected not least on the walls of Chinese restaurants up and down the country, which often boast framed pictures of Qingtian city.

“When you move abroad, you always ask yourself: ‘Do I have a friend or family member there or not?’ If you do, everything is easier. If not, it is so much more difficult,” says Mr Wang.

But family networks are not just crucial in deciding what country the Chinese choose as their destination. They also play a critical role in helping the new arrivals get started in business – by providing all-important access to finance. “If you want to open a bar or start a corner shop, you don’t go to the bank to ask for €20,000. You just ask 10 friends and family members for €2,000 each. One month after opening, you pay back the first person. The second month you pay back the next. The system works very well,” explains Mr Wang. It works, above all else, on the basis of personal trust and mutual dependency. “You never sign a contract. And you never ask for interest,” says Mr Chen, adding: “This is not a system or an application. It is all about human trust.”

It is possible to refuse requests. But by doing so a Chinese businessman shuts himself out of the intricate web of favours taken and favours owed that underpins his community. “Today I help you with a loan so you can open your shop. But tomorrow you help me to open my shop,” says Mr Chen.

It is a system that was born, at least in part, out of necessity. Like most migrants, the Chinese arriving in Spain typically lacked the assets, credit history and financial guarantees sought by banks. But it also reflects a broader mistrust of the official banking sector.

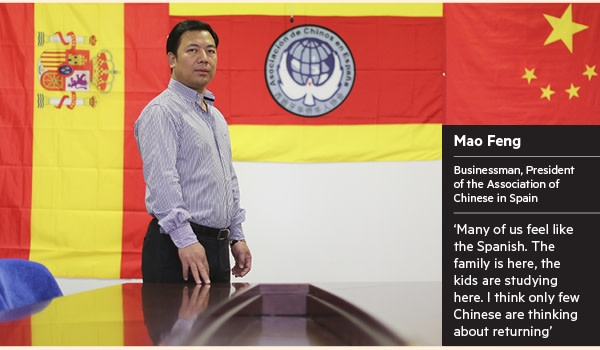

“The Chinese know that the bank always wins. So if we don’t have to ask for money from the bank, we don’t,” says Mao Feng, a Madrid-based businessman and the president of the Association of Chinese in Spain.

Business leaders and analysts agree that the cheap, flexible system of financing is one of the crucial reasons why the Chinese were able to weather the recent crisis better than most. Unlike their Spanish counterparts, the Chinese were largely insulated from the vagaries of the country’s tottering retail banking system. When lenders stopped the flow of credit to small and medium-sized companies, the Chinese were unaffected. And when a Chinese business had trouble repaying a loan, or paying staff salaries, it was usually easy to find a swift and flexible solution. Its main creditors, more likely than not, were not twitchy banks but family members and friends. Its workers, typically, were similarly close – and usually ready to accept a temporary wage cut.

“Who survives in a crisis? Those who have capital, or who have easy access to capital. And when the crisis came, the Chinese had their family network to fall back on to,” says Mario Esteban, of the Real Instituto Elcano in Madrid.

Personal savings played another big part in seeing the Chinese business sector through the crisis. “When a Chinese earns €1,000 he will never spend it all. He will always set aside €500 or so to make provisions for the future or to invest,” Mr Mao says.

Thriftiness and a capacity for hard work are at the heart of a business culture that has served the Chinese commercial class well – whether in Spain or elsewhere. Indeed, as much as they profess to admire Spain and the Spaniards, some Chinese find it hard to hide their disdain for some of the more carefree local habits. “When I tell a Chinese worker I need someone to work on a Saturday, he will do it and I’ll pay him,” Mr Chen says. “With a Spaniard, when I ask him to work on the weekend I have to negotiate. It is almost like I am asking him a favour!”

The Chinese community in Spain kept growing long after the economic collapse – and even as other migrant groups began to return to their home countries. Newcomers say that the more recent wave of Chinese migrants is different from Mr Chen’s generation. Many arrive by choice, not out of economic necessity. They come to see something of the world, improve their skills, but they are also a little less driven than the early entrepreneurs.

Yun Ping Dong, 27, came to Spain five years ago to study but has no plans to return soon. “Life is freer here, and calmer,” she says. “We want to enjoy life a little bit more.”

Work visas are harder to come by and – after decades of relentless economic growth in China – the economic gain of moving to Europe is not as clear-cut as previously. Some data suggest that the number of new arrivals from China is finally dropping off: migrants are still coming, but there are fewer, they are better educated, and often come for a specific job or to study a particular course.

“There is no reason to come to Spain any more. You live very well in China now,” remarks Mr Mao, the association president.

Yet just as the wave of migrants has crested, a new wave is building – this time bringing money and investment from China rather than workers and entrepreneurs. David Höhn, a partner at KPMG in Madrid, has watched it gather in strength since he began heading the accounting firm’s China desk in the Spanish capital. “The phone is hopping. It is as if someone lifted the barrier 18 months ago, and said: ‘Spain is OK now’,” he says.

What the Chinese are looking for is, above all else, expertise. Mr Höhn points out that most transactions involve Chinese groups buying minority stakes in Spanish companies, with the aim of launching joint ventures either in third markets or back in China itself. “Group A buys group B – that is not the way forward for the Chinese. This is about setting up alliances.”

Chinese companies have shown interest in sectors where Spain enjoys a strong record, such as tourism, food, infrastructure and construction. Over the past year, for example, Chinese investors have bought large stakes in NH, the Spanish hotel chain; in Campofrio, a maker of sausages, ham and other pork products; and in Osborne, the sherry group.

It is an approach that mirrors the one taken by Chinese companies in Germany, where they have bought into the machinery and equipment sector, and in Italy, which has seen a string of deals in textiles and fashion. “What they want is access to specific expertise and to technology,” says Mr Höhn.

In the case of Spain, he sees the tourism industry as a particularly enticing target for Chinese buyers. The NH deal aside, Chinese companies have also snapped up hotels across the country in an attempt to position themselves for the moment when Chinese tourists finally discover Spain.

The most headline-grabbing transaction so far has been the deal to buy Madrid’s landmark Edificio España, a Franco-era skyscraper that towers over downtown Madrid. Wang Jianlin, the buyer, plans to convert the building into luxury apartments and a hotel.

At a cost of €265m, the Edificio España deal is the most valuable so far. But there is also keen interest among Chinese buyers for apartments and houses worth just over €500,000. That is the threshold set by the Spanish government for awarding a so-called golden visa to property buyers from abroad. The trade-off is simple, and potentially attractive for both sides.

Spain gets a new stream of buyers to turn around the country’s faltering housing market, while foreign investors receive residency visas that allows them to travel freely within much of the EU.

Even as this outside investment helps the economy, it is prompting a broader sense of unease. Some view the Chinese and their fabled work ethic as a threat to the Spanish way of life. “The question people here ask is: ‘Do we have to work like the Chinese?’” says Mr Esteban.

That, indeed, was the unwelcome message delivered by Juan Roig, a Spanish supermarket magnate, at the height of the crisis. It failed to endear him or the Chinese to the broader Spanish public, which was (and still is) wrestling with sky-high unemployment and a painful drop in living standards. As Mr Esteban points out, polls show that Spaniards typically have a lower opinion of China than their counterparts in other European countries.

Chinese business leaders acknowledge that relations are far from perfect, but insist that the community is integrating well into Spanish society. “The first generation of Chinese migrants has a lot of difficulty with the language and with communication. They had no time to study. But their children study here in Spanish schools, they speak Spanish perfectly and they know Spanish culture very well. So I think things are getting better,” says Mr Mao.

He echoes a common sentiment when he argues that most Chinese living in Spain are here to stay. “Many of us feel like the Spanish. The family is here, the kids are studying here. I think only few Chinese are thinking about returning. They like life in Spain.”

Mr Chen, the founder of Don Pin, says there are countless things he likes about life in his adopted country. But he, for one, has no desire to grow old in Madrid. “When I die, I want to die in my village. I arrived here when I was 18 but I still feel my roots very strongly. But it is different for the children. My children will be Madrilians.”

Comments