Maison Bonnet: behind the making of the world’s most recognisable eyewear

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In the office above their Paris store in the Palais-Royal’s gardens, brothers Franck and Steven Bonnet are telling me about an American customer who has just come in and wants a pair of glasses. “He wants something today, right now,” says Franck. “And that’s not how it works.” While finding a good pair of glasses takes time and money, the perfect pair involves considerably more investment. At Maison Bonnet, which has been a family business since it was established in 1950, there’s almost nothing available ready-to-wear, and no express service. Most of the company’s business is wholly bespoke, involving 12 face measurements, and between two and nine months of work, with up to 30 hours of handcraft on each set of frames.

“We have ready-to-fit frames, but they account for maybe 10 per cent of our business,” says Franck, the “craftsman” and CEO of Maison Bonnet, which also involves a third brother, John. “The other 90 per cent is totally bespoke. And even then, the ready-to-fit frames need an hour’s fitting and customisation. We say on our website that we create 20 designs a year, and make 20 of each available, but that’s not true. We make a fraction of that because we don’t have the time or capacity.”

While the notion of a family business in luxury, from Hermès to Missoni to the Poilâne Bakery, brings with it ample storytelling, which is always handy for marketing, it also means that, usually, everyone involved cares a lot more about their product than they might otherwise. Their signature is on everything they do. And it’s inherently authentic. “My brother John looks after all of the tortoiseshell pieces with my father, who is the master,” says Franck. “John makes sure all remnants are upcycled, and we waste nothing. Then my mother, Marie-Christine, looks after administration, and I try to focus on a vision of the brand for the future. My 20-year-old nephew Matis, John’s son, is also now learning the trade.”

Maison Bonnet Jackie O 1960 frames, POA

Alber frames, POA

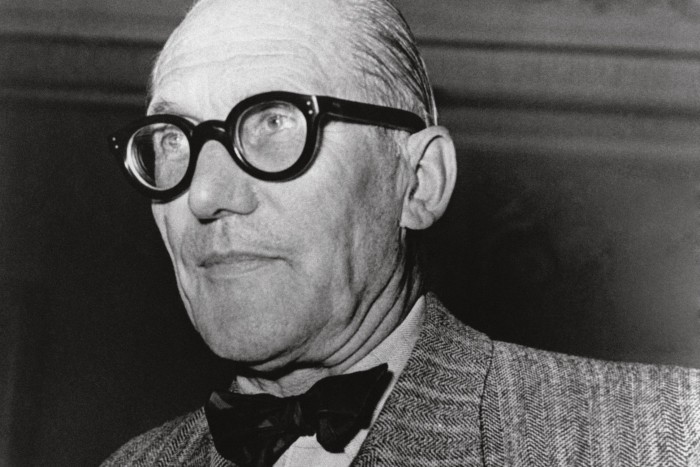

Only EB Meyrowitz and Tom Davies in London and Wesley Knight in Nashville are anywhere close to Maison Bonnet’s league. In France, Maison Bonnet is a national treasure. In 2000 it became the only lunetterie to be awarded the title of Maître d’Art, the government’s prestigious art and craft endorsement. Like champagne and Chanel, it is seen by the French as a brand that defines quality and refinement in an international ambassadorial fashion. Christian Bonnet, the brothers’ father, began learning how to make glasses from his father, Robert, at the age of 14. Robert had founded Maison Bonnet in 1950 after learning the craft from his father Alfred. Loyal customers like the architect Joseph Dirand have been drawn to Maison Bonnet by its historic significance – in Dirand’s case it was the fact that they made Le Corbusier’s distinctive frames.

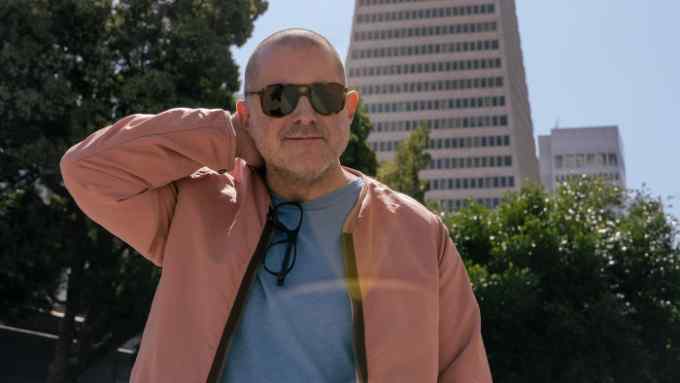

I suspect that Le Corbusier would have come to Maison Bonnet with fully formed ideas about what he wanted to rest on the bridge of his nose; as would Jony Ive, another Bonnet-wearer known for having an uncompromising vision about shape and structure. “Often we ask if they have ideas about what they are looking for, but they say they come to us because we know what we are doing,” says Steven, head of creation. “When we first met Jony, we didn’t love what he was wearing. He didn’t like progressive lenses, he just had glasses for reading, constantly resting on the tip of his nose and looking over the top of them, like a grandpa. It was a fight to get him to consider a design that actually fitted his face, with lenses that he could keep in place for a meeting, at a screen, and to read notes.”

There’s a long list of famous Bonnet customers: Jackie Onassis wore the “figure eight” glasses, and Jacques Chirac and Audrey Hepburn were also clients. But perhaps the most iconic frames belonged to Yves Saint Laurent. When people come to the store in London or Paris, they regularly ask for something in the YSL style, and the Bonnets ask: “Which era?” For Saint Laurent, flawed eyesight became an opportunity to disguise himself. “He was incredibly shy,” says Steven. “When my father made his first pair of glasses, he had come up with an outline, but it wouldn’t work. It covered the brow line, which you should never do. It makes your expression invisible. But with each new pair, he wanted them more angular, and larger. He wanted to hide.”

Maison Bonnet glasses are, because of their bespoke nature, all about personal style, whether for the shy or the extrovert. But it’s often one of the Bonnet workers who ascertains what that style is and offers suggestions. One of the few clients to come with a fixed idea was interior designer Christian Liaigre, who brought along a pair of the French equivalent of NHS specs. “They are quite industrial, and actually nice,” says Franck. “They come in just one design, and Liaigre wanted that design, but altered to fit him perfectly, and made in a noble material. That was one of the few times that someone else took hold of the pencil and got involved with the design process. We added twists, then fabricated them in tortoiseshell.”

Specs appeal

Maison Bonnet’s famous wearers

The Bonnet family are known for their use of tortoiseshell, which is one of the rarest materials you can use for frames. They stress that they are cruelty-free; only shells from turtles that have died from natural causes are used, and the older the turtle is, the thicker its shell, so there is no point in “fishing”. The material is also incredibly long-lasting and can be repaired with a grafting process.

While tortoiseshell is beautiful and resilient, it represents only about six per cent of Maison Bonnet’s production; 20 per cent is buffalo horn, and the rest is acetate. When someone does want to invest in tortoiseshell (and costs aside, you’re looking at nine months rather than two or three for acetate), the Bonnets recommend a back-up pair for exercise, gardening or anything that gets you breaking out in a sweat, because moisture will ultimately damage the natural material. And their acetate is by no means a second best – if you compare the best acetate with high-street plastic frames, the difference is as apparent as cashmere next to polyester. “The quality of the acetate we use is superb; when we polish it for a customer, even the smell is different,” says Franck. “Italian and Japanese [acetate] are the finest. When you have such a small scale of production, you can select the best. If you’re making thousands of pairs of glasses, you aren’t going to budget for that.”

Just as no one’s face is symmetrical, no two frames are the same. If a bespoke suit involves the most precise measurements, then bespoke spectacle production demands forensic attention. A change in an angle or length is measured down to a tenth of a millimetre. The Bonnets are masters of measurement as well as making. And there are only eight people involved in the production process at the brand’s atelier in Burgundy. Many have been there for the long haul.

But how will they find the next generation of makers? “We’ve found that there are a lot of young people who are bored with living their lives on screen and want to be involved in physical craft,” says Franck. “We often get a call from a design school when they think they have found someone with skills that would suit us. There’s not a way to teach what we do, necessarily. Once we had a guy come to us who was a tattoo designer, and he had gorgeous drawing skills. Another guy used to make knives with blades in Damascus steel and handles in horn. Everyone on our team is an artist. It’s all about having intelligence of the hand.”

Comments