Out of office: the fathers bringing up baby

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Stanley jiggles, bounces, jiggles, bounces; the four-month-old’s face flickering from smiles to frowns and back again. His father, Ben Moody, unshaven but smart in a navy long-sleeved T-shirt, snatches sips of cappuccino in a café while deploying his body as both trampoline and rocking horse. “It’s harder work than my day job,” he says and smiles, aware that he echoes generations of working mothers before him.

For the next six months, the 34-year-old will be one of a growing number of British “latte papas”, as the fathers who juggle coffee and infants are known in Sweden. On weekdays, from 8.30am when his wife leaves for work until 6.30pm when she returns, Moody will be the one to wipe the curdled milk from his son’s chin, change his nappies and persuade him to nap, while taking parental leave from his job as the head of public affairs at JDRF, a diabetes charity based in north London.

Today, in the third week of his leave, Moody is grappling with ennui and elation, managing feeds, washing and God knows what else that sucks up the day. He had nurtured lofty ambitions for his time off. Before setting his out-of-office email message, he’d bought a stack of books; so far he has read five pages.

Sara, Moody’s 33-year-old wife, has taken a morning break to drop into the café in Stoke Newington, a pocket of north London crammed with organic food shops, toy stores and children’s clothes boutiques. Fizzing with energy despite the sleep deprivation common to all new parents, Sara says that though she loved being in a “little bubble with my baby”, she was keen to get back to work four months after Stanley’s birth. The start of the year is the busiest time at the architectural practice she set up three years ago, with homeowners commissioning kitchens, extensions and loft conversions. “I’ve worked flipping hard to get to this point,” she says. “If I just stopped, I’d really worry that I’d be starting again, effectively.” She struggled to leave Stanley but knows he is in good hands. “I don’t have to worry who’s looking after him.”

Moody is the first father from his group of friends, his antenatal group and his workplace to take this kind of extended leave to look after a baby. That he can do so is thanks to the launch of Shared Parental Leave (SPL) almost a year ago, a policy touted as a landmark social intervention by the then coalition government. SPL gives mothers and fathers the right to share up to 50 weeks of leave and 37 weeks of pay after the birth or adoption of their child. Discussing the rationale for the policy at an event in April 2014, Nick Clegg, the then-deputy prime minister, talked of the need for “radical change” that would “sweep away those Edwardian rules which still hold back those families working hard to juggle their responsibilities at home and work”.

Moody believes the experience will transform the way his family operates in future. “Without this time and practice, I would just be handing [Stanley] off to his mum every time he was upset,” he says. “It’s going to shape how we are as parents for long beyond the six months that I take off.”

Yet, while it may be changing lives on an individual level, on a national one, SPL take-up has been underwhelming. According to research by Working Families, a UK charity dealing with family life and work, between 0.5 and 2 per cent of eligible fathers had made use of the provision six months after the rules changed. The government had predicted a take-up of 2 to 8 per cent in the first year. Why such limited progress? “There are many men who would love to spend more time raising their children,” notes Maria Miller, the Conservative chair of the women and equalities select committee, “but [they] feel unable to because of the impact on their careers and earning ability.” Social policies take time to bed down, of course — and a fuller picture should be available in 2018, when the government plans to report in detail on the impact of the policy — but the implementation of SPL has revealed workplace biases and intergenerational clashes.

. . .

In Britain, working women have been guaranteed maternity leave and the right to return to the same workplace ever since the 1975 Employment Protection Act provided for up to 29 weeks of leave for each pregnancy. The duration of leave has gradually increased to its current 52 weeks. Men had to wait until 2003 to be granted the right to statutory paternity leave, and then it was limited to two weeks’ duration, to be taken immediately after the birth.

In other northern European countries, particularly in Scandinavia, men have for many years been able to share responsibility with women for childcare. Sweden set the example in 1974, becoming the first country in the world to replace maternity leave with gender-neutral “parental leave”. In the UK, the idea that parents should be allowed to choose how they divided up the job of caring for a baby was only established in 2011, after a Labour government introduced Additional Paternity Leave (APL), giving fathers the right to take up to 26 weeks of leave. But the policy was limited: the father could only take leave once the woman had returned to work, the leave could only be taken in one single block, and it could only start once the baby was 20 weeks old.

The SPL rules that came into effect in April last year aim to remove those limits, putting mothers and fathers on a more equal footing. After a mother’s mandatory two-week maternity leave has ended, parents can now share up to 50 weeks’ leave between them. They could, for example, take 25 weeks off together, or take it in turns, while receiving 37 weeks of statutory shared parental pay between them, of £139.58 a week, or 90 per cent of earnings, whichever is lower, although employers can choose to “enhance” earnings.

While hailed by the coalition government as a way of encouraging fathers to be more involved in family life, satisfying parents’ desires for flexibility and overcoming sexist assumptions, the rules also fit into a broader economic policy: the government wants to encourage mothers to return to work. As productivity levels slow and the population ages, the UK and other developed economies are trying to make full use of their resources, including women and older workers. “Harnessing the potential of female workers [could] become an increasingly important source of competitive advantage,” says Yong Jing Teow, an economist at the professional services firm PwC. Research by PwC shows the UK could boost its GDP by 9 per cent if it could increase the proportion of women in work from 68 per cent to match the 73 per cent seen in Sweden, the highest-performing country.

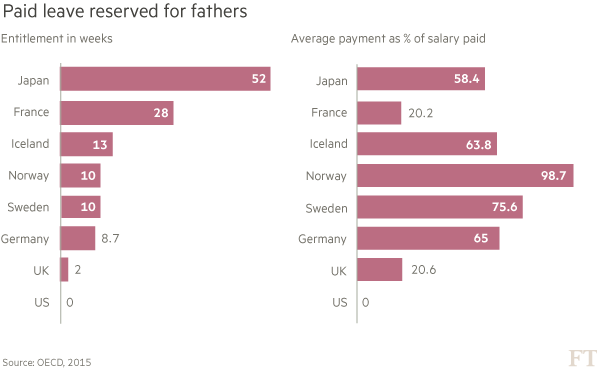

The UK is not alone in wanting to increase female productivity. In Japan, where mothers are far less likely to work than in the UK, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is committed to increasing women’s participation in the workforce, calling for “both men and women [to be] able to focus on child rearing . . . and then making it possible for them to return to their workplaces with surety”. Norway, Sweden and Iceland have each introduced “daddy quotas”, a period of leave exclusively for fathers, as a way of forcing fathers to make use of parental leave. In Sweden, it was not until the introduction of the 30-day “daddy quota” in 1995 that men started to use their leave in significant numbers; today, Swedish fathers take one-quarter of all parental leave. The policy is considered so successful that in January this year the daddy quota was extended to 90 days.

. . .

When Jonathan Kay, a 31-year-old solicitor at Addleshaw Goddard in Leeds, told his parents that he was going to take 20 weeks off to care for his baby son Benjamin, his father, a furniture maker, turned to Kay’s mother and said, “They live in a different world to us.” Kay has taken shared parental leave so that his wife can return to work as a dentist. “It’s always been important to me [that I would] have children and spend time with them,” he says.

The cultural shift observed by his father was, of course, happening long before the introduction of SPL. In the UK, the proportion of dual-income couples far outstrips families relying on a male breadwinner. According to a recent study into “Modern Fatherhood”, conducted by NatCen Social Research, the University of East Anglia and the Thomas Coram Research Unit, the proportion of households with two full-time earners with children increased from 26 per cent in 2001 to 31 per cent in 2013, while only 22 per cent of households relied on sole male breadwinners in the same year. Divorce and separation have had an impact too; more men are looking after their children alone, at least part of the time. A growth in the number of gay fathers has also helped transform fatherhood — the Office for National Statistics’ last estimate, in 2015, suggested there were about 10,000 dependent children living in same-sex-couple families.

As gender equality has advanced, the idea that mothers in the UK could take up to a year of maternity leave while fathers received only two weeks has become increasingly anachronistic. Sarah Jackson, chief executive of the charity Working Families, points to a striking change in attitudes in the past two decades: “Younger fathers have an expectation of equality at home.” Research published by her organisation earlier this year shows that more than one in five fathers now report sharing childcare responsibilities, with younger fathers the biggest group, although mothers remain the primary carers. Studies have also shown that children benefit from more involved fathers, both in terms of emotional bonds and educational achievement. A recent report by the OECD stated that where fathers participate more in childcare and family life, children “enjoy higher cognitive and emotional outcomes and physical health”.

Despite the social shifts of recent decades, traditional ideas about the roles of men and women, particularly when it comes to caring for a baby, remain deep-rooted in the corporate world. Men who reduce their work in order to care for children fear being stigmatised, which could partly account for the low take-up of SPL, says Joan Williams, founding director of the Centre for WorkLife Law, a non-profit research and advocacy group based at the University of California. Williams says work can function for men as “a masculinity contest. It’s kind of amazing some men are willing to say ‘no’ [and ‘yes’ to paternity leave].” Some of the cultural resistance to young fathers’ desire to work more flexibly, or to spend time with their babies, reflects intergenerational conflict, she believes. “The older generation has a lot invested in proving they were good dads. They see their identity at stake and are taken aback when younger generations want to take leave,” she says.

This intergenerational clash is something that “Edward” knows all too well. A 33-year-old finance lawyer based in London, he is visibly stressed: his tie skew-whiff, his grey suit crumpled. He does not want his real name to be used in case his employers, who have a progressive image and offer enhanced pay for fathers on leave, recognise him.

A year ago, Edward cut his working week to spend time with his three-year-old daughter. He had to first argue with a line manager who had asked if it would not be easier if his wife, also a lawyer, gave up her work instead. In return for 80 per cent of his pay, he typically crams 70 hours’ work into his week, including on his day off and weekend, he says. He bills the same hours as a full-time employee despite his reduced wages.

Edward feels his part-time status has made him a target at his company. “They’re a lot more pernickety with their criticism of my work.” They have told him that he is unlikely to make partner now. “They view these kinds of arrangements as showing a lack of ambition,” he says.

The argument behind his long hours is that lawyers must be available to respond to clients’ demands. But according to Edward: “The clients I’ve worked with, they’ve been really good about it . . . They’ll often just say, ‘I know you’re not in, keep it until Monday.’” He feels his employers don’t have “a concept of a day off”. One of his peers barely saw his daughter for the first nine months of her life, he says.

While he has thoughts of quitting his job “all the time”, Edward is unwilling to concede defeat; in part because he has “worked bloody hard to get there” and also because he feels a responsibility to challenge the norms. “It has opened my eyes [to] women in the City and the exodus of [female] talent.”

When asked how he feels about the prospect of returning to full-time work, his fluid chat falters; the idea of barely seeing his daughter in the week upsets him. While he concedes he does not have as much time for work as he used to before he had children, he believes it could be easier if his employers were committed to making it work. “There could be more innovation. There’s a reluctance to test [flexibility].”

Linda Haas, emeritus professor of sociology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, has studied fatherhood and work for decades, particularly in Sweden. She says the attitude of individual companies and managers is key to the success of policies like SPL. The best employers monitor the quality of work that staff are given after they have been granted flexible work arrangements or extended leave: checking that the type of projects, events or opportunities do not become less demanding or of lower value. “Some employers celebrate dads who have taken leave. They assume developed management skills.” She cautions against overpraising the Swedish model, noting that “fathers take more leave in [public organisations] than in the private sector”. And while it is part of the Swedish cultural discourse that men participate in childcare, “women still do the majority”.

One look at Japan shows that government policy on its own will not change behaviour. According to the OECD, Japan has “by far the most generous paid father-specific entitlement”: new fathers are entitled to 12 months’ paternity leave, on almost 60 per cent of their salary. Yet take-up is low: about 2 per cent, in a country where most people don’t even take holiday. The prime minister has said he wants this to increase to 13 per cent by 2020.

In a few competitive sectors, employers have seized on paternity leave as a new weapon in the war for talent. In the US, which has no statutory paid parental leave for men or women, Facebook offers four months’ paid leave to look after a baby in the first year of its life. After his daughter Max was born last November, Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive and founder of Facebook, took two months off to spend time with her. Netflix offers 12 months’ paid leave to US employees in their child’s first year. Even the banking sector, worried about losing talent to tech giants, has upped its US leave policies. Bank of America Merrill Lynch, for example, offers fathers 12 weeks’ leave.

Pay makes a huge difference. In the UK government’s assessment of the future impact of SPL, it found that in Sweden, Norway and Iceland, where new parents receive at least 60 per cent of their pay while on leave, between 85 and 90 per cent of fathers take some time off.

Lack of pay has a disproportionate effect on low-income families: better-paid fathers are more likely to take leave than lesser-paid fathers. If a mother is already working part-time, perhaps because she is at home looking after older children, losing the father’s salary will be even more damaging.

In the UK, some employers offer fathers the same terms as female employees taking maternity leave. James Bardrick, head of UK operations for Citigroup, says that matching fathers’ pay to that given to mothers would be good for “retention and employer reputation”. It would also benefit female employees, he notes, “as the focus shifts from ‘mothers as carers’ to ‘both parents as carers’”.

Moody and Kay both stress the importance of the enhanced pay they receive while on leave (which matches their employers’ maternity leave). Bruce Lightbody, a 53-year-old partner at Addleshaw Goddard, is Kay’s boss. He says he is committed to making sure that both men and women can access parental leave. “A lot of our younger people want a great career but they also want to enjoy bonding with a child. I don’t see these positions as incompatible.” While he has sympathy for small businesses who complain about the cost and headache of covering for fathers’ absences, he says solutions are out there. “You need to look at ways that are innovative. Though often the answer is staring you in the face.” In his own firm’s case, they developed AG Integrate, a pool of self-employed solicitors who can cover for fathers who are on leave.

Kay was heartened by his employers’ attitude. A company-wide email announced the enhanced pay and encouraged eligible employees to go on leave. “They weren’t sneaking it out. It was there in black and white.” Because the firm was positive, he does not worry about the impact on his career; clients, too, were encouraging, he says.

Enhanced pay for fathers, flexible work practices and supportive line managers are, however, far from common. A paper by psychologists from Rutgers University published in the Journal of Social Issues found that men who ask for family leave were feminised for “acting like a woman” and deemed poor workers.

“John”, a sales director who asked to remain anonymous, approached his manager last year to request a month’s shared parental leave. It was declined. He was told that if he pushed the issue, his job might be eliminated. “Obviously nothing was put in writing”, he says. “I was gutted but had little option left.”

On the face of it, John’s treatment looks unlawful, says Sarah Henchoz, an employment lawyer at Allen & Overy, as an employer cannot refuse a request for shared parental leave unless the request is for broken periods of leave; for example, one week on, one week off. “Where the request is for one solid block of leave . . . the employer cannot refuse it,” she says.

. . .

Jo Swinson, who pushed through the legislation in her role as business and women and equalities minister under the previous government, describes SPL as a “step change”. The former Liberal Democrat MP, who now works as a consultant advising companies on diversity, says the legislation has started a debate among couples and employers about a father’s role. “We have to recognise there’s cultural barriers,” she says. “Maternity leave is well entrenched in the workplace but [fathers taking] leave is new . . . They are pioneers, not just in the workplace but even at mother and baby clubs.” She observes that it is only when men take advantage of the new legislation and, as a result, learn to juggle family and work that they will appreciate the difficulties traditionally faced by working mothers.

In the UK, some see SPL as a hollow gesture: without a period of leave dedicated specifically for fathers or higher guaranteed pay, it will have limited appeal. Professor Margaret O’Brien, director of the Thomas Coram Research Unit at the Institute of Education, describes SPL as a “wasted opportunity”. While conceding that the principle and the “sharing” rhetoric is important, the policy is flawed, she says, because in effect mothers have to give up some of their own leave for their partners. The Lib Dem party’s original plan to offer all fathers a dedicated month’s paid leave — a Scandinavian-style “daddy month” that would not be transferable to the mother — was dropped in 2012, under opposition from business and the Conservative party.

Others see the policy as out of touch with the modern workforce. Brendan Donegan, an anthropologist at the London School of Economics, recently took shared parental leave with his wife Carrie, also an academic, and their daughter Caitlin. SPL, he says, is geared to those in long-term jobs working for one employer. “The job market is becoming more precarious,” he points out. His wife’s leave coincided with the last few months of her employment contract and his need to put in for research funding to extend his own work at the LSE, meaning between the two of them they were juggling job and funding applications as well as academic publications. “We’re not really switching off from the office. The leave has turned out to be a mirage.”

The Trades Union Congress says that even before the introduction of SPL, many men missed out on taking two weeks’ paid paternity leave because they did not have the required length of service with their employer, or were self-employed or agency workers. Parental leave may be out of sync with the short-term, multiple-employer nature of many jobs these days.

Chancellor George Osborne’s announcement last year that grandparents could qualify for SPL in the future could also dissuade fathers from taking it. The plans would mean that working grandparents could take time off, sharing parental leave pay in order to help care for babies.

When I catch up with Ben Moody a few weeks later, he tells me he has taken his son to baby cinema to see Star Wars, Room and Spotlight, but mostly they go for walks in the park. Having a baby with him has been an icebreaker — strangers approach him for chats, an unusual experience in London. He concedes he has been lucky but is optimistic about the future, believing more men will take the leave, and business might adapt too. “We’re in this transition from an old model, where men went out to work, and women usually took care of childcare,” he says. “It sounds silly to say that we’re still in transition but we are.”

Emma Jacobs is the FT’s Business Life writer.

Photographs: Jo Metson Scott / Webber Represents

Comments