How architects cracked the egg: ovoid buildings through the ages

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Egg. It looks and sounds like an embryonic word, gestating until it grows a few syllables. It apparently comes from the proto-Germanic word “ajja”, but sounds Palaeolithic. How can cavemen not have blurted “egg” once in a while? One suspects the French hold a similar theory about “oeuf”.

The primitive simplicity of eggs represents nature’s most resolved work of architecture — the design process of aeons could refine the thin ovoid shell no further than it had achieved by the Jurassic age. The wall of an egg is calcium carbonate — found in concrete — and its efficient strength lies in its arc, a structure intended to contain and protect life.

Many cultures began their mythical origins from a cosmic egg, in which the earth was born from a shell separated into domes. The Brahmanda Purana, a Sanskrit text, is named after the Hindu “cosmic egg” (Brahma-anda), probably written in the 4th century, and we are left to wonder how far early domes represented those celestial eggshells.

By that time, the ancient Greeks had long celebrated the life of eggs juxtaposed with the barb of death in the “egg-and-dart” moulding used for the scrolled Ionic and leafy Corinthian orders. The device may have emerged from painting parades of soldiers holding shields and spears on terracotta jars. The Romans caught hold of this classical language and never dropped the eggs. By way of the Renaissance, thousands of country and town houses across Europe and the Americas host eggs and their darts by the millions on fireplaces, cornices and capitals.

The Christian tradition juggled with those classical eggs as symbols of birth and rebirth — also Virgin birth, given Job’s theory that ostriches hatch by themselves from eggs left in the desert. Practically, Gothic cathedrals share the structural principle of the egg, in that the pointed end of an eggshell approximates the catenary curve: the arc of a hung chain representing the strongest line. The curves of medieval arches are closer to this ideal than round arches: Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome of Florence cathedral is based on a catenary — though being octagonal, it is a polygonal egg shape. Monumental egginess belonged to later centuries.

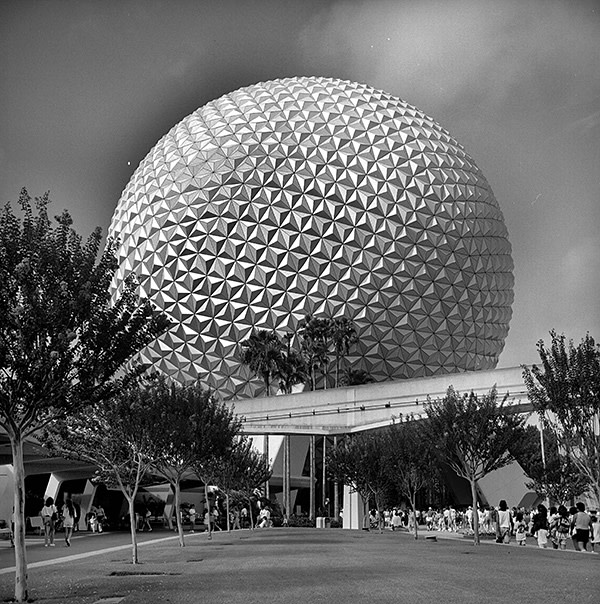

Bruno Taut’s pavilion at Cologne’s Werkbund Exhibition in 1914 introduced an egg-shaped skeletal frame, a forerunner of the “geodesic domes” later developed in Germany, before being lavishly credited to the American engineer Buckminster Fuller. Yet triangulated metal frames failed to crack monumental egginess as these self-supporting structural balls tended to remain simple spheres such as Disney’s visionary Epcot Centre. Unlike Taut’s triumph, they were somewhat pointless. The freedom to create ovoids demanded plasticity, whereupon concrete came to the rescue.

As a professor at Columbia University, Frederick Kiesler was frustrated by the boxiness of commercial architecture. His Endless House project of 1950 was a pile of three or four cracked eggs, whose space would flow freely within their shells, a continuous surface that encouraged light to sweep through and act as a poetic metaphor for life wherein “all ends of living meet . . . they touch one another with the kiss of time . . . secretive or obvious, or through the whims of memory.” His model and drawings were exhibited at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1958-59, but a concept it remained. Nonetheless, that concept proved influential.

In the heart of Albany, New York’s state capital, sits The Egg. The concrete half-shell on its spiky cup was designed by Wallace Harrison in 1966 as a concert venue housing two theatres — a double-yolker. Wrapped around the main concert hall is its albumen, the lounge of the Kitty Carlisle Hart Theatre. The Egg took a dozen years to build.

Beijing also went for a big egg concert hall with its National Centre for the Performing Arts, built between 2001 and 2007 to the designs of Paul Andreu. Like Harrison’s concrete building, this is a half-shell, but it is the top half of a skeletal egg, its transparent glass and titanium frame set within a lake to conjure its base through reflection.

In Hong Kong, James Law has dedicated his architectural career to building comparable skeletal eggs. His bold vision “embodies new levels of innovation, technology and creativity to build better, healthy and smarter cities”, smarter because free spaces can, if they are well conceived, optimise light and climate better than air-conditioned boxes. Law says the problems of manufacturing and construction quality that plagued the industry of geodesic-dome builders are now much less significant, as “new technologies allow for curved glass to be shaped, cut and applied to more free-flowing shapes without being prohibitively expensive”.

Concrete is vying for supremacy. English architect Kathryn Findlay, who died in 2014, was an inspirational champion of the sculpted ovoid. Her legacy is maintained by Mike Oades, who worked with her on the (unfinished and now demolished) Doha villa and gallery for the late Saud bin Mohammed bin Ali al-Thani, once the world’s biggest art collector who also had a passion for preserving rare birds.

Oades is now principal of Atomik Architecture, with offices in London and Kazakhstan. He explains Findlay’s philosophy of design as a dualised principle of hard and soft yolks: either the soft yolk yields to the existing shape of its container, or a soft wrapper respects the shape of a hard-boiled yolk. This fundamental distinction allows for ingenious plays of space around fluid and rigid forms. Oades maintains that the desert environment is ideal for elevated concrete eggs, which allow airflow to cool beneath, while keeping sunlight out and regulating heat by their mass.

“Ex ovo omnia” (“everything comes from the egg”) as the physician William Harvey wrote in 1651. We were all eggs once. And increasingly we are building eggs in which to live. You will be the judge of whether that is progressive or regressive.

Photographs: Danita Delimont/Alamy; FilippoBacci/Getty Images; Irving Penn/Condé Nast; James Law Cybertecture; John Cameron/Alamy; Roger Viollet/Getty Images; ullstein bild/Getty Images

Comments