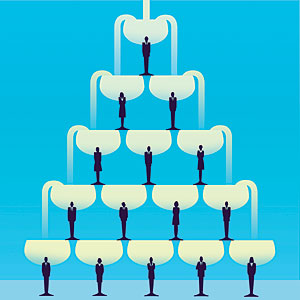

The trickle-down effect

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For decades companies have faced the conundrum of how to ensure managers can implement what they have learnt at business school when they are back at work. Management guru Henry Mintzberg, scourge of business school complacency, sums it up succinctly: “You should not send a changed person back into an unchanged organisation, but we always do.”

Now Mintzberg’s Desautels Faculty of Management at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, among others, is addressing the issue of how to ensure the dollars invested in the classroom convert into dollars for the corporate bottom line.

One idea gaining currency is that of “cascading”, in which every manager who has been on a campus-based course has to teach a group of more junior colleagues back in the workplace. It has been more than a decade since Duke CE, the corporate education arm of Duke University, North Carolina, US, promoted the concept, but advances in workplace technology are accelerating its adoption.

“The leader as teacher is very effective,” says Ray Carvey, executive vice-president of corporate learning at Harvard Business Publishing. “The leader goes back and cascades [what he or she has learnt].”

This is just one of this year’s executive education fashions, as technology-enhanced learning and open programme certification gain traction.

Technology may be the hot topic in executive education, but implementation is rare, says Susan Cates, president and associate dean of executive development for Kenan-Flagler business school at the University of North Carolina. “There is an awful lot of conversation, but it is not a significant part of the business,” she says.

This has not stopped David Thomas, dean of the McDonough school at Georgetown University, Washington DC, ranked 34th in its debut in the FT’s customised rankings. Within three years, 25 per cent of all the content will be delivered online, he says. “We will use executive education as an experimental platform to leverage online learning.”

Prof Thomas says he is committed to doubling revenues from executive education at the school over the next five years. But his confidence is not shared across the industry, says Melanie Weaver Barnett, chief executive education officer at Michigan Ross in the US. “What surprised me was how quickly [the market] came back after the recession, but then it went flat,” she says.

All agree that in the US it will be programmes designed for individual companies, rather than their open enrolment counterparts, that will grow. “It is no longer about developing capability but about helping the company towards their strategic goals,” says Barnett.

Cates at Kenan-Flagler also has concerns about the market for open enrolment programmes. “As companies are making decisions about where they spend their money, it is harder and harder to invest in programmes for individuals,” she says. “It is difficult to track that back to the performance of the company.”

Where open enrolment programmes are successful, it is often because the schools are accrediting them with transferable certificates. At Georgetown this has been particularly effective, says Prof Thomas. “A certificate allows us to design around what is needed, rather than design it around the hoops of a degree programme.”

The Rotman school at the University of Toronto has taken a similar approach, says Michele Milan, managing director of executive programmes. However, Rotman has gone a step further by partnering with other Canadian business schools to teach the programme across Canada. “Everything is leaner,” says Milan. “We have learnt to be agile and creative.”

Schools realise that increasingly they have to teach where the business is, as companies cut travel budgets. Unsurprisingly, the domestic open enrolment market in Spain is shrinking, according to Josep Valor, associate dean of executive education at Iese Business School, which is doubling its open enrolment teaching overseas – in Brazil, China, Russia and the US.

IMD in Switzerland is setting up international hubs in Singapore and Brazil, says Dominique Turpin, the school’s president. “We are hearing from the market that we need to address the challenges the companies are facing in emerging markets.”

New locations affect schools’ headcount, says Mike Canning, chief executive of Duke CE, which has laid off staff in the US. “We had a mismatch between where we were and where the staff were. We had too many people in the US and are hiring elsewhere.” Duke CE is opening an office in Singapore, and business is booming in Africa, says Canning.

Developing markets brings its own problems, says Camelia Ilie, dean of executive education at Incae in Costa Rica. “There are not so many American and European schools here because of the cost.”

But the market is booming to the extent that Incae is launching 30 new open enrolment programmes this year. Dr Ilie joined Incae from the Spanish business school Esade. “I thought I would find a market as dynamic as Spain 10 years ago, but it is much more dynamic,” she says.

Comments