How the private equity industry stole a march in European payments

Simply sign up to the Fintech myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Just over a decade ago, processing electronic payments was largely regarded as a dull back-office function, including by the banks that did it.

A deal this week to create one of Europe’s largest payments companies is a reminder of a group that took a very different view and stepped into reap the rewards: private equity firms.

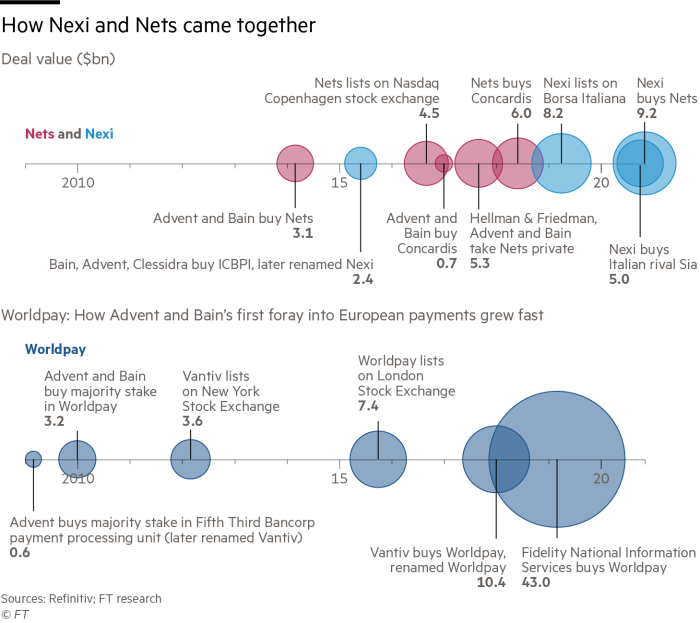

Italian payments group Nexi acquired Danish rival Nets for €7.8bn, combining two businesses that began life in banks but were then carved out and run by buyout groups Advent, Bain Capital and Hellman & Friedman. Nexi snapped up Nets just weeks after striking a tie-up with domestic competitor Sia, a run of deals that will value the group at €22bn.

Payments companies help merchants accept in-store or online payments, charging a proportion of the value of each transaction. With the need to invest in technology creating high fixed costs, the payment sector’s model has unleashed a race for scale well suited to the dealmaking that underpins the private equity industry.

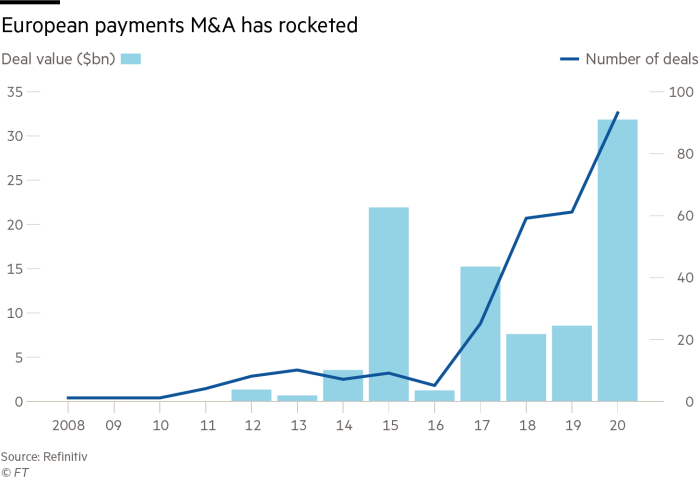

The pandemic has done little to cool the pace of acquisitions. Almost $32bn of transactions have been struck in the European payments industry this year, up from $8.5bn in the same period in 2019, according to Refinitiv.

The relentless acquisitions have helped catapult the market value of the payment industry’s biggest players, including newly expanded Nexi and French rival Worldline, above some European lenders, underlining how banks failed to capitalise on the opportunity.

Owning payment companies “has been one of private equity’s biggest investment successes”, said Charles Hayes, a partner at law firm Freshfields which has advised on several deals.

Nexi and Nets were not the private equity industry’s first foray into payments, and nor are buyout groups the only ones to have scrambled for a foothold in a fast-growing market. But their tangled history illustrates how private equity stepped in where many banks had failed to capitalise, just as ecommerce and digital payments took off.

Tangled history

In 2014, Advent and Bain snapped up Nets, itself forged five years earlier from the merger of two Nordic bank-owned payments groups. A year later, the firms, alongside the Italian private equity group Clessidra, bought Istituto Centrale delle Banche Popolari Italiane (ICBPI), founded shortly before the second world war by a group of Italian banks. They renamed it Nexi.

A dizzying whirlwind of takeovers, take-privates and listings was only just beginning for Nexi and Nets.

After listing in 2016, Nets was taken private the following year by a consortium led by Hellman & Friedman and including Advent and Bain. In 2018, Nets snapped up German payments group Concardis, also owned by Advent and Bain. Meanwhile, Nexi hoovered up a series of smaller payments groups before listing in what was Europe’s largest initial public offering of 2019.

“It has been an incredibly successful subsegment to focus on — definitely one of the most interesting we’ve seen in private equity,” said James Brocklebank, managing partner at Advent. “It’s a question of focus . . . banks recognise these are good businesses [but] are not necessarily in the best position to develop the technology and to spend the money on driving payments as its own profit centre.”

The takeovers have left a legacy of relatively high debts. Nets’ net leverage is 4.8 times, and the combined group with Nexi and Sia will have 3.3 times, according to an investor presentation. After the Nets deal, 38 per cent of Nexi’s shares will be in public investors’ hands. Most of the remaining will be held by Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, the Italian government vehicle that backed Sia, as well as Advent, Bain and Hellman & Friedman.

What few dispute is that the industry’s push into payments has been lucrative. Since 2008, buyout firms’ investment in the payments sector have returned 2.7 times the amount of equity invested, compared to 2.1 times for financial services deals and 2.3 times in technology, according to a report this year by management consultancy Bain & Company.

The aggressive inroads into the European payments industry by buyout firms was made possible by the Payment Services Directive, a 2009 piece of legislation from the European Commission that paved the way for non-banks to provide payments services.

The expansion has not been without controversy.

In 2010, private equity made its first major move into European payments. Advent and Bain Capital bought Royal Bank of Scotland’s payments business at a £2bn valuation after EU regulators forced the bank to sell the unit as a condition of its bailout during the financial crisis.

By the time the business, renamed Worldpay, floated in London in 2015, it commanded a valuation of £6.3bn. Just two years later, US payments processor Vantiv swallowed it for £9.1bn. Based on Worldpay’s IPO valuation, the buyout firms made a return of 5.4 times the equity they invested, according to an analysis by Peter Morris, an associate scholar at Oxford university’s Saïd Business School. Advent and Bain declined to comment on the deal’s returns.

The giddy increase in Worldpay’s valuation led some politicians to complain that UK taxpayers suffered a raw deal in the original sale in 2010. Last year Natwest, until recently known as Royal Bank of Scotland, got back into the industry, launching a service enabling small businesses to accept card payments in-store or online.

Race for scale

The race for scale is only intensifying — and not just among the industry’s private-equity backed groups. In February, Worldline agreed to buy rival Ingenico for €7.8bn. In the US, the $43bn acquisition of Worldpay by financial tech specialist Fidelity National Information Services in early 2019 prompted panicked rivals to get bigger still.

“The process of consolidation will continue,” said Luca Bassi, a managing director at Bain Capital who oversaw the Nexi deal and sits on the company’s board. “There are a lot of countries where banks haven’t sold out their business.”

But this year has not been straightforward for the payments industry, with the fraud at German group Wirecard focusing regulators’ attention on the lighter-touch treatment the industry enjoys compared to banks.

At the same time, the economic disruption unleashed by the Covid-19 pandemic hit consumer spending, sending global revenues of payment groups tumbling by about 22 per cent between January and June, according to McKinsey — though industry executives insist a long-term shift towards online and contactless payments will ultimately offset that.

“The only thing that’s bad for us is payments in cash,” said Mr Bassi. While some electronic payments generate higher fees than others, he said, “everything where cash isn’t there, is good.”

In Nexi’s home market of Italy, for example, electronic payments represent only 25 per cent of all transactions, and Rome has recently vowed to fight tax evasion by encouraging digital payments.

The buyout groups will probably sell down their stakes in the new Nexi business over the next few years. As they do, the payments industry that disrupted the banks is facing a fresh threat of its own: the prospect of a technology giant launching a global rival that, like China’s Alipay, offers merchants lower fees — or could cut out the intermediary altogether.

That is “a massive risk,” said one private equity dealmaker who specialises in financial services but has not invested in the payments industry.

“Nobody really knows where payments is headed — will it be in the cloud, or over blockchain?” he added. “Everybody is trying to get as big as possible so they can influence where payments ultimately ends up.”

Comments