Artist Leonardo Drew’s explosive sculptures draw order from chaos

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I didn’t know who Leonardo was until I went to Catholic school,” says American artist Leonardo Drew. “Before that, my name had just got me beaten up at public school. So that’s one thing I owe to those nuns. The one thing . . . ”

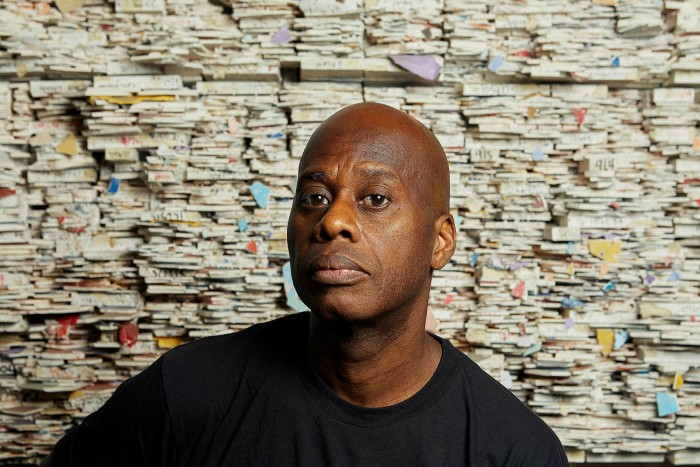

Drew, it turned out, shared not just a name but an exceptional talent for drawing with the Renaissance polymath, although his artistic reputation, seamless and sustained for more than 30 years, derives mainly from his explosive sculptural work.

Now 61, imposingly tall and slender and frequently sporting a dashing leather cap, he has shown at major institutions including the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington and the Hammer in Los Angeles; he has a sprawling permanent installation in the Harvey Milk terminal at San Francisco airport; and in 2019 he laid 100ft of decorated carpet in New York’s Madison Square Park — a crumpled metaphor for home and sanctuary — along with a mini cityscape made from wooden blocks.

“Had to be careful there,” he says of the park, which is framed by the Flatiron and the Empire State Buildings. “You’re in the presence of monsters like that, you need to make concessions to your surroundings — or you’ll get the shit kicked out of you.”

Drew’s next context is the decidedly un-park-like ambience of Unlimited, the section of Art Basel that takes place in a gritty hangar of a hall and is dedicated to super-scaled works. If Drew faced iconic buildings in Manhattan, here the neighbours will include Rachel Whiteread’s sublime “Untitled (Stairs)” from 2001 and Isa Genzken’s creepy arrangement of dolls under sun umbrellas from 2007. But there’s little fear that Drew’s assemblage — of hundreds of shards of painted plywood that sputter off the wall and seem to shatter and spin across the floor — will be overlooked. His work has a pent-up power and magnetism, an atomised complexity that draws viewers to it.

I first met Drew in London earlier this year, a few hours after he finished installing an exhibition in Goodman Gallery’s elegant white cube. Sculptures bristled energetically on the walls: black-coated timber fashioned into twisted, petrified branches; wooden panels hairy with finely crafted wooden quills. An installation occupied the entire back wall of the lower-ground gallery: skinny sticks of painted wood, forms embellished with reels of tape, accretions of wooden scraps, a rolled-up ivory-coloured rope carpet, all arranged in a grid.

Though they could be mistaken for found objects, the myriad parts are studio-made, with precision and care, from fresh materials, then patina’d with paints and resins, sand and rust. To install them, he lays them across the floor, then mounts them one by one. “I go in with a plan,” he says of his process, “then you feel the space and you jump in. I become the weather and it takes shape around me.” The final effect is monumental and microscopic, a confection of order out of chaos.

Drew seemed a little anxious that day in London, probably tired from his flight, possibly nervous. It was his major London debut. The next time we speak, though, he is in his studio in Brooklyn and unstoppably upbeat. He lives on his own above the studio, a former garage building with 30ft-high ceilings on the ground floor. “I don’t have much of a life,” he says merrily. “I need to be in contact with my work 24/7.” His neighbours, he says, can’t really make him out, this rangy guy in dirty overalls, who has this big building and has just bought the house next door. “They’re ham-and-eggers, with regular jobs. But they love me because they get to use my parking space.”

Drew is used to cutting an unusual figure. He was born in Talahassee, Florida in 1961, and the family moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut when he was seven. “That was when my mother threw my father out,” says Drew. Times were hard for him and his four brothers, and his obsessive drawing of superheroes did not impress his harried mother, though it did his mentors at the local community centre, who had his work shown at the country clubs of nearby Westport. This brought Drew to the attention of executives at both DC and Marvel comics, Mad Men types who made the daily commute to Manhattan. “I was this one black kid in the room, and these white guys were buying my work,” says Drew, who was then 13. “I was well-trained in race relations from an early age.”

If Drew hadn’t discovered Jackson Pollock in the local library, he would probably be a star of comic illustration today. Instead, he put down his pencils and went to study at Cooper Union under Jack Whitten, the radical Alabama-born painter. He started working with dead animals, “to get below the prettified surface. I was thinking about death, because it’s the tough one, the unknown.” He learned to cure hides and clean bones and by 1988 had created a work combining blackened feathers, bones, skins and wood that spoke of deterioration and chaos and reflected life in the projects, where he’d grown up, and on the streets of New York, where he now lived. Robert Longo chose his work for a group show in 1989 called Young Turks. “He said, ‘You deserve the attention,’” says Drew.

Since then, Drew has worked in series. For a while his chosen material was unbleached cotton, with its embedded narrative of slavery and the American South. He experimented with oxidisation on metal and with burnishing wood. He was inspired by travel — a trip to Gorée Island in Senegal and its blood-chilling remnants of the slave trade; a visit to Machu Picchu resonant with the traces of the ancients.

“I have ideas, and when they’re worked out of my system, I move on. From 2004, I just worked with white paper for a while. I’d been rusting and burning things, but I found that the emotional charge of blank whiteness was just the same.” He wrapped up bicycles, and guns, and typewriters, hanging them from strings in Boschian tangles, fetishising American life.

Traces of more recent journeys will be seen in his installation at Basel. For the four years leading up to the pandemic, Drew had been visiting Jingdezhen, a centre of porcelain production in the north-east of China. “That was when colour started affecting my work,” he says. In 2019, for a show at Lelong gallery in New York, he created an exuberant installation (“Number 215”) of hundreds of wooden parts painted with patterns then broken, distressed and frozen in mid-flight frenzy. Passers-by were drawn into the gallery from the street to leap around in its energetic force field.

One day, CBS anchor Anthony Mason walked past, and shortly afterwards Drew was in front of the cameras, explaining his art to the nation. “We all carry a collective weight,” said Drew then. In Basel, he’s the one throwing it up in the air again, seeing where it all lands.

Comments