Francis Bacon/Maria Lassnig, Tate Liverpool: ‘Myriad connections’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“The only reality is pain”: Kafka’s summing up is quoted by Maria Lassnig in her writings on her own art, and it informs all Francis Bacon’s work. What a stroke of curatorial inspiration at Tate Liverpool to show these painters together, in two impressive solo presentations, independent yet sparking myriad connections.

Bacon and Lassnig, born within a decade of each other — 1909, 1919 — fought the same battles: to paint figuratively during the heydays of abstraction and pop; to convey the anguish of the human condition when irony and conceptual games held sway. Both staged the figure in artificial space, both set out to translate bodily sensations into paint.

But on other fundamentals facing mid-20th century painters — the uses of photography, expression of self — they were polarised. Tate’s juxtaposition sensitively unravels opposing strategies and possibilities.

Lassnig’s is straightforwardly an art of autobiography. Her most famous painting is the confrontational, bald, wrinkled, naked old age self-portrait “You or Me”, in which she holds two guns, one pointing at her own head, the other at the viewer: it says that her relationship with the outside world is so troubled that to express herself in paint was a matter of survival.

Liverpool opens with the large-scale 1960s “Harlequin Self-portrait” and “Figure with Blue Throat”, evocations of Lassnig’s cropped body set down in economical, fluid, ravishingly coloured painterly lines, with the white canvas as torso. They take their stance from art informel and are about subjectivity, boundaries between self and exterior. The show closes with blisteringly frank self-depictions of extreme frailty: sagging body fragmented and doubled on an institutional bed in “Hospital” (2005), the defiant “Self-portrait with Brush” (2010-13) where the left arm and hand wielding the brush are incomplete because at the age of 94 Lassnig could barely hold it.

An urgent yet loose, sensual handling, and a Fauvish palette of heightened flesh tones from rose to crimson, occasional brilliant yellow or bright blue grounds, interspersed sometimes with toxic greens or sickly yellows, lasted her life. She could be witty, as in her self-portrait “Lady with a Brain”, in which her brain is placed outside her head as a difficult appendage. Or sarcastic, as in “Kitchen Bride”, which depicts a cheese grater bowing in deference. But always the drive was to depict what the body feels like within.

A space-age techno-nun enclosed in a plastic veil, Lassnig suffocates in “Self-portrait under Plastic”. Blind with domestic rage, mouth shrieking wide, neck constricted by red bands, she turns a cooking pot into a blindfold in “Self-portrait with Saucepan”. In “High Seated Female Figure” she is so hemmed in by the pressure of a confining armchair that her body morphs into it. “Pink Electricity” is orgasmic, torso and upper legs abstracted into luminous pulsating pink waves.

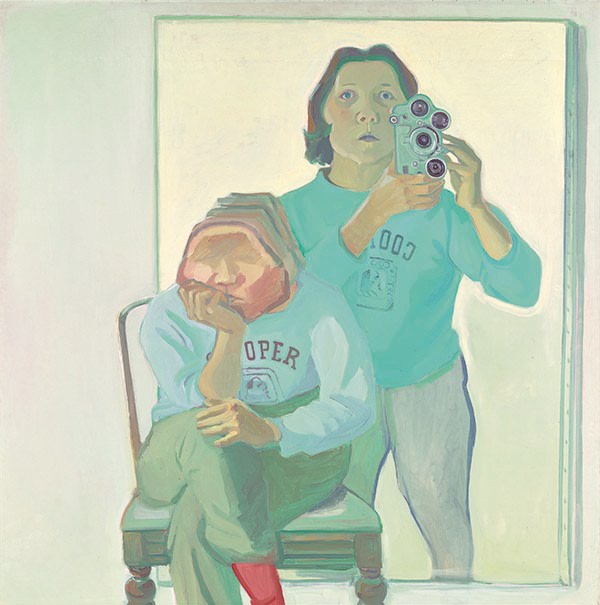

So intensely does paint represent feeling here that you understand why Lassnig rejects photography as an unthinkable mechanical intrusion into what painting does. She called photographers “protheses artists”. “Double Self-Portrait with Camera” shows Lassnig as the camera would render her appearance — banal, moderate — and as she feels: a monstrous, squat, depressed figure.

Repeatedly she draws attention to her medium. In “Inside and Outside the Canvas” a figure has climbed through the canvas and wears it like a dress. In “Self-portrait with Stick” an enormous stick — brush? crayon? — merges with her body, while behind, on a canvas-within-a-canvas, is a portrait of an elderly woman, Lassnig’s mother, whose hands project into the picture’s “real’ space, resting on Lassnig’s shoulder: a psychodrama of control and liberation, artifice and emotion.

Lassnig, little known outside her native Austria until her last decade (she died in 2014 at the age of 95), is the revelation of Liverpool’s double bill. The reason her art does not dwindle before the power of Francis Bacon, the greatest postwar figurative painter, is because it is so subjective, even narcissistic, that it demands to be taken only on its own terms. (An animated film, The Ballad of Maria Lassnig, whose jazzy strains enliven the show, is comically self-absorbed.)

Bacon demands the opposite. “The very great artists were not trying to express themselves. They were trying to trap the fact,” he said. Aping Velázquez’s sumptuous surfaces and grandeur of composition in the velvety purple 1950s popes in “Figure Sitting” and “Study for a Portrait”, or deconstructing Picasso’s deconstructions, and throwing in filmic and photographic sources — in the wildly cruel “After Muybridge ‘The human figure in motion’: Woman Emptying a Bowl of Water and Paralytic Child Walking on All Fours” — he went for timelessness: pictures which would end up in “either the National Gallery or the dustbin, with nothing in between”.

But Bacon is never simple. He also admitted that his crucifixion compositions — the ghostly silver 1933 “Crucifixion” and “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion” (1944) launched his oeuvre and open this exhibition — were “nearer to a self-portrait”. The art historical motifs, the twisted, sprawling, leaking figures who howl, wrestle, suffer, die, in the triptychs, all transform autobiographical experience — savage beatings by his father, masochistic relationships with lovers Peter Lacy and George Dyer, their lonely deaths — into modern myths of alienation and futility. A standout loan from the Hirschhorn in Washington DC is “Triptych Inspired by TS Eliot’s ‘Sweeney Agonistes’”, tight multi-hued canvases of battered dissolving bodies on a sort of trampoline that condense nihilism into vast sweeping formal rhythms, as Eliot did.

That triptych also starred at Tate’s Britain’s massive 2008 retrospective, and Liverpool’s show, the largest ever devoted to Bacon in the north of England, feels essentially like a scaled-down version of that London exhibition, with a welcome stronger focus on the earlier period — Bacon’s greatest. Collaborating with Stuttgart’s Staatsgalerie, Liverpool has garnered stellar German-owned works: Düsseldorf’s caged “Man in Blue V”, Stuttgart’s “Chimpanzee”, eerily close to Bacon’s bestialised human forms, Frankfurt’s silky screaming “Nurse from the Battleship Potemkin”, Berlin’s awkward sexy “Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho” before what looks like a car morphing into a bull.

Liverpool’s subtitle “Invisible Rooms” proposes a theme about trapping the image in a space frame, but since Bacon placed almost all his figures in such transparent cages, this is neither basis for selection nor offers fresh illumination. Bacon insisted his reasons were formal — “I cut down the scale of the canvas by drawing in these rectangles which concentrate the image down” — rendering Tate’s attempt to organise by content (“Cage”, “Arena”, “Body/Sculpture”) irrelevant. It doesn’t matter: Bacon is Bacon, his nightmarish claustrophobic vision magnificently offset here by the open views of the Mersey in the most compelling, beautifully hung show I have seen at Tate Liverpool.

To September 18, tate.org.uk

Comments