Nissan’s parable of shoddy governance

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

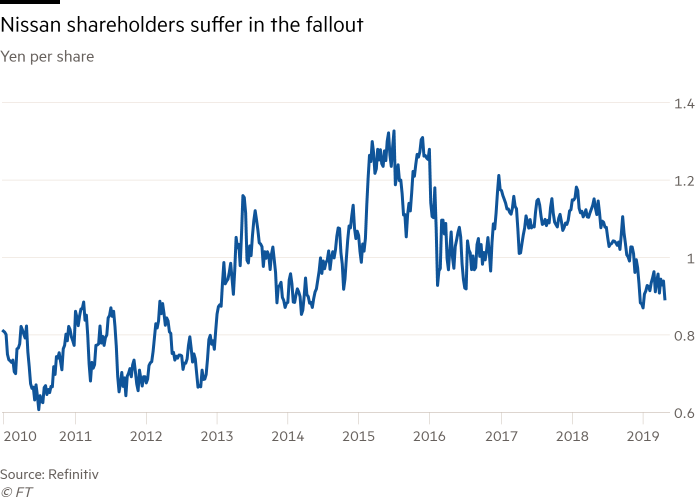

Just hours after Carlos Ghosn was led away by prosecutors from a private company jet at Tokyo’s Haneda airport last November, Nissan was already characterising the fiasco — at least in part — as a crisis of corporate governance.

At a fraught press conference that evening, Hiroto Saikawa, Mr Ghosn’s handpicked successor as Nissan chief executive, declared his “indignation and despair” at the overall situation in which Nissan’s chairman had been arrested on suspicion of financial misconduct. But he quickly homed in on the structural problems created by his mentor’s 19-year “regime”.

Nissan came under heavy fire for its own corporate role in allegations that included Mr Ghosn submitting accounts that understated his pay — and within three days the company had announced it would set up an independent panel to probe its governance shortcomings.

Many long-term Japan-watchers sensed a landmark moment — not just for Nissan, but for investors’ decades-long campaign for serious and sustainable improvements to Japan’s standards of corporate governance.

If it were possible to look beyond the fireworks around Mr Ghosn’s arrest and his personal culpability, argued governance experts, the whole episode could work as the ultimate parable for where shoddy governance can land you.

Japan has spent the past five years trying to take the governance question mainstream. On orders from the administration of Shinzo Abe, prime minister, it introduced its first stewardship and governance codes in 2014 and 2015 respectively. These included demands for more transparency, a greater ratio of independent directors on boards and measures to ensure equality of minority shareholders.

The codes were widely viewed as important breakthroughs, but frustrations soon emerged. In a 2017 paper, Ken Hokugo, director of corporate governance at Japan’s Pension Fund Association, criticised the pace of progress. Much of the change in boardrooms, he said, had been “perfunctory and without strategy”. Indeed, at the time, sellside analysts focused on ranking levels of governance improvement among Japanese companies cited Nissan as one such example of this.

Nissan’s determination to interpret the Ghosn crisis as one of governance was initially welcomed as an example of what one shareholder called “conceptual progress”: it was important, the investor told the Financial Times, that the language of governance had entered the public discourse and that it was being used in connection with such a high-profile scandal.

Yet also vital to this progress was the idea that the alleged malfeasance of an individual — in this case one of the most famous business figures in the world — was a symptom of more fundamental, structural problems with the way the company was run. Nissan appeared to be admitting that the company lacked the basic checks and balances required of properly run listed entities.

It would not take a particularly aggressive self-investigation by Nissan to confirm that, said Zuhair Khan, Japan strategist at Jefferies, a broker. “We were not particularly surprised that Nissan had another scandal,” he wrote in a note to investors the day after Mr Ghosn’s arrest. “The company’s board structure raised many red flags in 2017 and the improvements in the board in June 2018 were superficial.”

Despite Mr Ghosn’s status as saviour of Nissan from the edge of bankruptcy in 1999, his leadership of the company, argued Mr Khan, had latterly caused it to stand out, even in a Tokyo stock market riddled with governance shortcomings. When Mr Ghosn stepped down as its chief executive in 2017, Nissan was one of only 11 companies in the Topix 500 index that still did not have two independent directors.

Worse — and arguably more pertinent to the financial malfeasance accusations levelled against Mr Ghosn — was the fact that Nissan did not have separate board committees to oversee remuneration, audit or appointments, even though this structure had been adopted by 75 per cent of the largest Japanese companies. The carmaker “had literally no governance structure”, Koji Endo, head of the equity research department at SBI Securities, said at the time of the arrest in November.

In late March 2019, Nissan’s special committee for improving governance published the findings of its investigation into the “root causes” of the Ghosn imbroglio and how it could “establish a governance structure worthy of a world-leading company”. In many respects, said analysts that had previously been critical of Nissan’s governance, the report appeared to propel the company in the right direction. It called for three statutory board committees, ensuring that a majority of board directors are independent, and building better protections for whistleblowers.

The list represents an acknowledgment by Nissan of its most obvious governance flaws and a plan to remedy the most glaring.

But, analysts say, that does not mean Nissan will suddenly be transformed into a governance paragon for Japan Inc to follow: the committee has made recommendations, but there is no guarantee they will all be adopted and executed properly.

The governance report was also laced with condemnation of Mr Ghosn for the concentration of power in his hands and his role in the governance crisis. It may therefore overstate the extent to which Nissan’s problems will be solved by his absence. But even more glaring is the report’s lack of scrutiny of the stewardship role played — or not — by Renault as a 43 per cent holder of Nissan’s shares.

Until the governance implications of that arrangement are addressed, say its smaller shareholders, Nissan is likely to continue to raise red flags.

Comments