The Renaissance, reborn

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A few years ago the artist Natalia González Martín was stuck. “I had fallen out with my practice a bit. I didn’t know where it was going,” says the Madrid native, now 27, not long graduated from art school in London. But one day she found a spare wooden board and decided to create an image of the Virgin Mary, the likes of which she had seen countless times in the Prado as a child. “It was suddenly so enjoyable again,” says González Martín. “This image was literally like an apparition.”

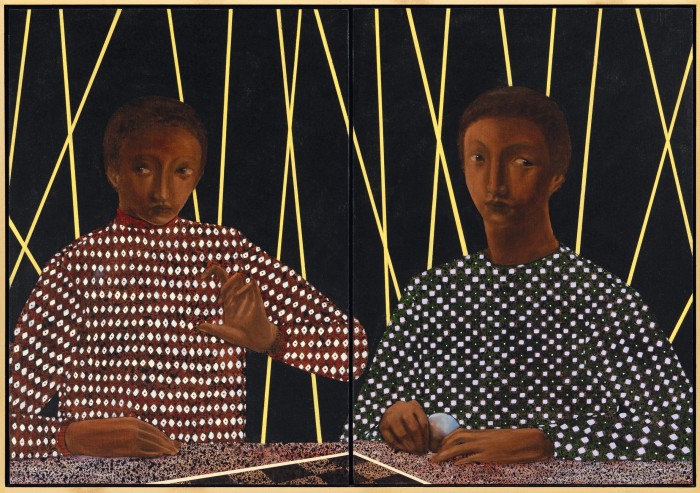

González Martín’s small, delicate pictures, last seen at a solo show at London’s Hannah Barry Gallery and in the group selection New Mythologies at Huxley-Parlour, make her part of a surprising trend. Artists are returning to the eternal source of inspiration that is the Renaissance, that broad, loose term that covers more than two centuries of cultural revolution. From Ella Walker’s quattrocento-style paintings of Dantesque characters to Jem Perucchini’s elegant gold-tinted portraits of Medici-era youths, passing by Chris Oh’s crystalline tributes to Flemish-painted saints, a new generation is honouring the styles, subjects and forms of the late 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. They are modernised with little twists: one of Walker’s figures, for instance, might be decked out in latex. Add to that Louise Giovanelli’s ongoing dialogue with the Old Masters, where the painter uses classical techniques to create shimmering, mysterious canvases, or the fact that rising duo Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings have recently unveiled a series of frescoes in Tate Britain (albeit portraying everything from architecture to Suffragettes), and it’s clear that the era is having, well, a renaissance.

For González Martín, the influence is “undeniable”, she laughs. “A bit too much!” She can’t even remember the first time she saw a Renaissance painting, having seen so many in Madrid’s museums growing up. She also can’t deny that her Spanish Catholic upbringing is present in her images of bloody shrouds, Titian-ish nudes and angelic wings. Her images trick you slightly, portraying everyday activities in a Renaissance way: her take on a holy shroud, for instance, is also just mascara smudges on fabric. But while her subjects draw on the soft and sensual Italians of the 16th century, her technique is more inspired by the earlier The Descent from the Cross, by Rogier van Der Weyden, or her favourite, van Eyck. They are still a benchmark, she says. “In real life, those paintings make me want to quit, because I really cannot figure them out... It’s just so impeccably done and executed.”

Walker also favours the early Renaissance period. “It’s very much the 14th- and 15th-century stuff that I’m into – the way they paint, they use space, the flatness of the work,” says the Manchester-born 29-year-old, who is preparing for a show in a European institution next year. At Frieze 2021, Walker took over Casey Kaplan’s booth with seven huge canvases populated with knights, maids, saints and martyrs, rendered variously in acrylic, tempera, gesso, pastel and ink. On one level, the Renaissance makes itself felt in her palette: raw sienna, vivianite (a deep indigo-blue), dioxazine violet, iron-oxide red, caput mortuum (or cardinal purple), sap green. On another, it’s just the “gothic, macabre essence of that period” that she loves. “I’m not interested in painting skinny jeans!”

Unlike González Martín, neither religion nor art featured heavily in Walker’s upbringing; at best, she remembers her grandma having “little images of saints and things in her house”. When she did get to art school, she was mostly obsessed with Marlene Dumas. Yet a weekend in Florence in 2016, just after graduating from art school in Glasgow, sparked something: she visited Masaccio’s famous Brancacci Chapel, painted in the 1420s. “That was the first time I’d ever seen a fresco,” she says. “There’s just a lot of power and a lot of drama [in it]. I’m not really a religious person, I didn’t really go to church as a kid – so being in those spaces as an adult, as someone who’s interested in paint, it was quite overwhelming.”

Subsequent study at London’s Royal Drawing School confirmed Walker’s new passion. One class required drawing one painting in the National Gallery for a whole term, returning to it week after week: she chose The Baptism of Christ by Piero della Francesca, now her favourite artist. But, like her peers, Walker isn’t interested in just straightforward copying. Her figures are often inspired by contemporary looks she has seen on catwalks, or a favourite book, Fellini’s Faces, which features screenshots of all the great director’s characters. “I like the idea that some of my figures would look quite classical – but that they could also be in a contemporary dance sequence, or in a pop-music video.”

Why the Renaissance now? It doesn’t ever really go away, says González Martín. Ever since her “apparition”, she has noticed how much Christian iconography perseveres in popular culture, whether in the oeuvre of Beyoncé (the singer’s latest album is, of course, titled Renaissance), or the last LP by FKA twigs – Magdalene. In terms of visual art, she also points out that since painting has enjoyed such a huge return to figuration in the last few years, “you have to look” at the Renaissance masters, including even those she calls “the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” (Michelangelo, Leonardo, Donatello, Raphael) who people often take for granted. “You cannot avoid them if you are looking for references on ways to paint. Ignoring this whole tradition is almost impossible.”

This is taken to its most extreme instance by Callum Innes, whose recent show, Tondos, at Sean Kelly in New York, was inspired by the tondo, the circular image favoured by the likes of Michelangelo and Botticelli. It is a surprising twist for Innes: the Scots 60-year-old, shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1995, has always been known for a very modern abstraction and, true to form, his paintings don’t seem figurative at all – large slabs of red or purple bisect the canvas, bleeding right through to the edge. But then his inspiration is surprising too. It was a commission by Sotheby’s to paint four cask-ends of whisky barrels for a charity auction that introduced him to the idea two years ago. “I hadn’t really considered it until then,” he says.

For Innes, the Tondo is primarily a way of playing with form and colour. “It brings you straight into the subject matter,” he says approvingly. “It’s a very physical thing.” Past masters did inspire him: he cites Dirk Bouts’ famous Annunciation, from 1470 (“the use of red in that painting is so extreme”), or Botticelli’s Madonna of the Pomegranate, which is dominated by an equally striking blue. Yet it isn’t a totally fresh start – at art school in the 1980s, Innes produced various figurative paintings heavily influenced by Raphael. We won’t be seeing them any time soon, though. “Thank God, I’ve destroyed most of those!” Every artist, it seems, is allowed their own renaissance.

Comments