The Diary: Shawn Donnan

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

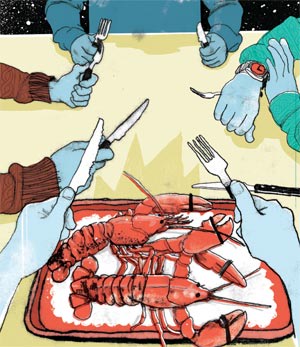

Bar the occasional interregnum, I have been coming to Pemaquid Fishermen’s Co-operative for lobster since the 1970s. And, since my son Aidan was born eight summers ago, and my wife and I decided to make Maine our regular holiday destination, a journey to the seafood eatery on the state’s midcoast has become an almost annual pilgrimage. I have difficulty eating lobster anywhere else. Even in Maine. When, eventually, Aidan and his little sister Lucy choose to crack their first lobster (they both currently prefer hot dogs as summer fare), I will do everything in my power to make sure it will be from the Pemaquid Co-op.

The Co-op lays claim to being the oldest continually operating one of its kind in the US. It has, naturally, grown over the years but essentially remains what it has been since 1947: a shack staffed by gangly teenagers working summer shifts. You bring your own beer, wine and salad and, if you are smart, mosquito spray and a tablecloth for your picnic table. You sit. You contemplate the sunset over Pemaquid Harbor while you wait for your lobster. The kids play in the little playground. It is a comfortable, early-to-bed corner of America that has changed very little over the years.

On this particular Saturday night, however, the Co-op is buzzing and by the time we arrive it’s clear that not everyone is feeling content. A crisis has hit the kitchen. Too many people are bypassing the lobster and the steamed clams, and ordering fried food instead. Tempers are flaring and there are rows breaking out over tardy, or even missing, orders of “chicken tenders” and deep-fried mozzarella sticks. The lobster and steamers come quickly. But, as is the case with many other parties, the hot dogs and fried food for the kids and Rachel, my non-seafood-eating wife, are held up in a greasy queue.

This is odd. For the first time I can remember, more people are opting for the aforementioned chicken tenders, or the fried haddock, than the lobster and the Co-op is struggling to cope.

The root cause is the price of lobster. It is too cheap and has been so for too long, which means people are taking it for granted. The price paid “at the dock” has been hovering around a 30-year low for the past two summers thanks to a glut – apparently caused by climate change and, er, Canadians (who harvest too much, according to their Maine competitors). The result is an affliction any luxury retailer would worry about: the lobster’s brand is in retreat.

Things aren’t quite as bad as they were in colonial days. As the late author David Foster Wallace wrote in “Consider the Lobster”, an essay published in Gourmet magazine in 2004, New England’s early settlers had so much lobster on their hands that they used the rotting crustaceans to fertilise their fields. “Even in the harsh penal environment of early America, some colonies had laws against feeding lobsters to inmates more than once a week because it was thought to be cruel and unusual, like making people eat rats,” he wrote.

But the situation now is dire enough that the industry is pushing for change. A new marketing body has been established and trade missions sent across the border to Canada to encourage better co-ordination. Paul LePage, Maine’s Republican governor, has sent lobsters to all 49 other US state governors. The hope is they will urge their citizens to eat more lobster.

I’m not sure that will work. But I am happy to do my part.

…

On our way out of Maine towards New York we make a pit stop at Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox. Family friends have given us tickets to a Sunday afternoon game, allowing Aidan to make his first visit to his father’s temple. Fenway, which is celebrating its centenary, is the oldest ballpark in America. It is also at the centre of what has been a remarkable civic reaction to the Boston Marathon bombing. “Boston Strong” T-shirts are everywhere. The traditional delivery of “Sweet Caroline” in the eighth inning break – which Neil Diamond flew in to lead straight after the attack – carries more emotion than it did in years past. A victory over the visiting Colorado Rockies ensures we leave with big smiles.

On the national baseball scene, however, steroid scandals are back and the game, which should have exorcised its drug demons years ago, is again in crisis. Attendance is down in key markets such as New York, where the storied Yankees, arch-rivals of the Red Sox, also happen to be floundering. The latest scandal has seen the suspension of more than a dozen players linked to a shady Florida clinic. Among those suspended is Alex Rodriguez, the Madonna-dating superstar known as “A-Rod”, to whom the Yankees once handed the biggest ($275m over 10 years) contract in baseball.

To be fair, the Red Sox did their part last year to add to the cynicism. After they fell out of contention thanks to the worst September collapse in baseball history, the Boston Globe lifted the lid on a squad of spoiled stars, at least three of whom hid in the locker room during games, drinking beer and eating fried chicken rather than supporting their teammates.

This year’s incarnation, though, is very different. A young team with a new manager, they have led their division for most of the year and New England has fallen in love all over again. At the heart of the team is Dustin Pedroia, a 5ft 8in infielder with a scrappy beard who looks like a flappy-eared plumber’s apprentice. He is the anti A-Rod, a determined working-class hero rather than a preening Hollywood pretender. So this summer, as the baseball world was gorging itself on Rodriguez gossip, the Red Sox quietly gave Pedroia a $100m, eight-year contract that will ensure he will see out his career in Boston.

Let the rest of America turn on its game. Aidan and I are with the Red Sox and Dustin Pedroia.

…

Breaking Bad is something I won’t be sharing with my eight-year-old son just yet. For those not in the know – and until this trip I was one of those people – it’s a hit US television show. The main character, Walter White, is a chemistry teacher who, faced with financial ruin, begins clandestinely producing the drug crystal meth to support his family. The whole thing turns very dark, very quickly. The show’s success has generated an odd boom in the city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, where it is set. According to a radio report I wake to on Sunday, tours of gritty neighbourhoods featured in the show are selling out. “You know, it’s not like we’re going to see where Gone With the Wind was filmed,” one tourist intones. “We knew it was going to be scruffy.” Candy makers peddle baggies of fake meth sweets, and there’s even a spa that offers “meth scented” bath salts to fans.

What that says about America, I don’t know.

Shawn Donnan is the FT’s world news editor

Comments