Crisis in the Amazon: ‘Coronavirus does not wait, they die on the boats’ | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In skiffs and flat-bottomed ferries, people from Brazil’s Amazonian communities bring their sick relatives along the web of waterways that criss-cross the rainforest in search of medical treatment.

But by the time the boats dock in Manaus, the region’s largest city and a big river port, many of the patients on board are already dead.

“Coronavirus does not wait. They die on the boats,” said Arthur Virgílio, mayor of Manaus, a municipality of 2m surrounded by thousands of kilometres of jungle, referring to the “dozens” of boats that dock every day.

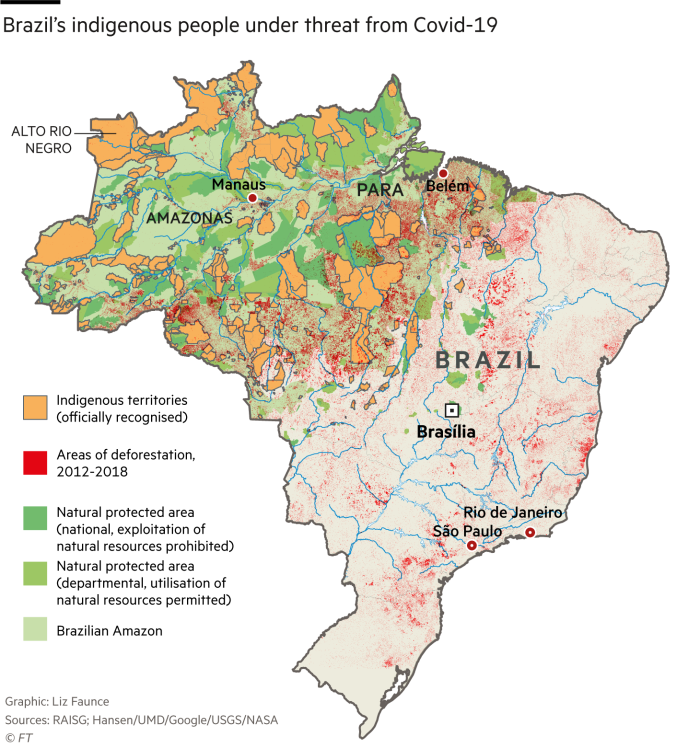

Vast, isolated and impoverished, the Amazon region has emerged in recent weeks as a flashpoint of the coronavirus pandemic in Latin America’s largest economy as the Covid-19 disease rips through communities with little access to healthcare and — in the case of the 1m-strong indigenous population — little immunity.

“At a max, our graveyards used to have 35 burials a day and that was in exceptional circumstances, such as a prison riot. Now we have an average of 130. We were not prepared for this,” said Mr Virgílio.

At more than 13,000, the death toll from coronavirus in Brazil is now the largest in emerging markets. Yet rightwing president Jair Bolsonaro has clashed with ministers, governors and mayors over how to handle the outbreak, dismissed the virus as a “sniffle” and is pushing for the economy to open.

The situation in the Amazon region has shocked many in Brazil, particularly following the publication of pictures of mass graves being dug with backhoes in some of Manaus’s four public cemeteries.

According to official figures in Brazil, more than 1,200 people have already died in Amazonas, the state that is the heartland of the country’s Amazon region and is one of the nation’s biggest and poorest. This is one of the highest death tolls of any Brazilian state, not far behind more densely populated states such as Rio de Janeiro.

“The number has been evolving very fast. We had an explosion of cases that started in April, we saw this explosion happening, and the collapse of the hospital network,” said Adriana Elías, a nurse in the public health system. Doctors and scientists are sceptical about the official figures. They “are completely outside reality. The number of deaths is many more times the official rate. The health system is collapsing,” said Philip Fearnside, a scientist living in Manaus. For Brazil overall, scientific models put the number of cases at over 1m, compared with official figure of 202,000.

Many of the deaths in the Amazon region have so far been concentrated in poor, suburban areas of Manaus, but a coalition of prominent scientists and celebrities this month wrote an open letter to the president, warning that vulnerable indigenous groups face “an extreme threat to their very survival” as a result of the virus.

“Fears of genocide are not exaggerated,” said Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist focused on the Amazon and a member of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. “The risk to indigenous peoples of this pandemic and the threats of invasions is very serious and could spell the end of indigenous culture, if not stopped.”

Remote indigenous areas, such as Alto Rio Negro on the border with Venezuela and Colombia, have already reported cases.

“I don’t understand how this virus arrived and spread so quickly, but the fact is that many of the villages have no infrastructure, personnel or equipment to offer service to indigenous people,” said Marciviane Satere, a leader from the Sateremaué tribe. “You have to come to Manaus and that can take up five days or a week by boat. Covid is demonstrating the fragility of the whole state.”

Scientists and indigenous chiefs argue that the threat of infection stems from illegal gold miners and loggers who, sensing a lull in environment protection since the beginning of the pandemic, have increased activity in the rainforest. Official figures showed deforestation in the Amazon increased more than 60 per cent last month compared with April last year.

There are also concerns about whether Mr Bolsonaro is committed to protecting the habitat of indigenous people in the Amazon region. Earlier this year, he said his government would present a bill to open indigenous lands to commercial mining and hydroelectric projects.

“The current policies of the government, combined with the pandemic, have raised old fears and led to the call for emergency measures to safeguard indigenous populations in the Amazon,” said Mr Nobre.

Despite the outbreak, a judge in Manaus this month rebuffed a request to implement a full lockdown, saying the state was already taking enough measures. The mayor disagrees. “Social isolation has not worked well in Manaus and there are two factors behind this: a little rebellion from the people and our president’s rhetoric,” said Mr Virgílio.

The mayor also criticised the lack of resources and support from the federal government, saying: “If there is no special care for the interior of the state, we may be close to mass deaths.”

Milena Kokama, a leader of the Kokama Indigenous Federation in Manaus, said she felt powerless and frustrated. “I am watching my people dying. I am a leader and I cannot do anything. While the government concerns itself with the economy, indigenous lives are being lost.”

Additional reporting by Carolina Pulice

Comments