From the ground up

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It was the skinny young children clustered at the sides of Dakar’s clogged roads that forced Ciré Kane into action. The gangs of barefoot boys in tattered clothes – some as young as five, many no more than 12 – are a common sight in Senegal’s cities, holding out plastic bowls and clamouring for small change and food from passers-by.

“It’s hard to not try to do something to help them when you see them all the time on the streets begging,” says Mr Kane, explaining what motivated him back in 2001 to start helping the vulnerable young people he saw all around him.

Many of these children are talibés, a word derived from Arabic meaning “disciple”, from Koranic boarding schools. Of the hundreds of thousands sent from rural areas and from neighbouring countries to these religious schools in Senegalese cities, as many as 50,000 are forced to beg by their teachers. Many are poorly fed and have been badly beaten; some carry out small jobs to earn the cash they are ordered to hand over.

“There is no group of young people suffering more than the talibés, and street kids in general. So it was impossible for us to not do something to support them,” says Mr Kane.

Along with some friends, Mr Kane – a graduate who had grown disillusioned with big development projects – took pens and paper into government schools after hours to work with talibés, children in conflict with the law and those who had dropped out of school. Soon, they began to go to the Islamic schools to talk about taboo subjects such as sexually transmitted diseases and substance abuse – dangers to which the talibés and others are exposed. For a year, they worked as volunteers, with no funding and no office.

Then, in 2002, they received their first support – a $4,000 grant from The Global Fund for Children. The organisation invests in “grassroots” non-profit groups that spring up locally and work with vulnerable young people and is the Financial Times’ partner in this year’s seasonal appeal.

Letter from the Editor

The staff of the Financial Times have chosen The Global Fund for Children, a pioneering charity helping some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable children, for our 2012 seasonal appeal.

Thanks to the generosity of our readers, the FT’s seasonal appeals have raised more than £9m for good causes since 2005. We aim to do even better this year.

To continue reading, click here

Mr Kane and his friends used the cash to revive a children’s centre that had fallen into disuse. Their operations grew, as did management support and grants – not just the $130,000 given by the GFC over seven years but also backing from donors such as the International Youth Foundation and the MasterCard Foundation.

Over the years, Mr Kane decided his group, called Synapse, would be of more use helping graduates and budding entrepreneurs find work. Youth unemployment runs at high levels in an economy forecast to grow at about 4 per cent in 2012, far below the rates registered in more buoyant economies in the region, such as Ghana. Every week, 200 young people come through the doors of Synapse’s multi-storey office block to make free use of the gleaming meeting rooms, training and support from 13 full-time staff.

Few donors support groups just starting out, says Mr Kane, but the GFC took a risk on him – and it paid off. Now, nearly two-thirds of those who have completed the organisation’s Passport to Employment course that prepares graduates for the world of work have jobs.

Injecting small bundles of cash and management expertise into a nascent organisation can lead to significant development gains later on, says Kristin Lindsey, GFC chief executive. Eight of the charity’s programme officers travel the world scouting for non-profit groups with annual budgets of less than $200,000.

“We are looking for groups other funders aren’t looking for, undervalued but with potential,” she says. “Finding groups that need capital and demonstrate strength, what they need is infusion of resources – [it] is very like venture capital.”

Money is only a small part of the help that the GFC provides. “It is not just providing financial resources; [it is] giving access to learning and networks and everything that organisation needs to thrive.”

They are searching for the next Grameen, she says in a reference to the pioneering Bangladeshi microfinance group that provides banking services for the rural poor.

The idea for the GFC stemmed from a visit by Maya Ajmera, its American founder, in 1990 to Orissa, one of India’s poorest states. Then a 22-year-old graduate, she saw barefoot children in tattered clothes attending classes on a railway platform. The teachers told her it cost just $400 a year to educate about 40 pupils. Struck by how much could be done with such a small sum, she asked herself: “How do you get capital to such organisations and how can we help them scale up their work?”

To learn more about the Global Fund for Children and to make a donation,click here

Ms Ajmera founded the GFC four years later. More than 8m children have since been reached by its partners, 1m in the past year alone. Since 1997, it has awarded grants worth almost $26m to 500 groups in 78 countries. In 2011-12, it gave more than $4m to about 300 organisations. The GFC aims to end these relationships after five to seven years, with the groups it has backed able to attract funding from those who would have shied away when they were getting started. About 92 per cent, including Synapse, which stopped receiving funding three years ago, are still going strong, says Ms Lindsey.

…

And these groups can have a real impact on the lives of young people globally. The GFC has several projects on the Caribbean island of Haiti, one of the world’s poorest nations, which was devastated by a 2010 earthquake that killed hundreds of thousands and displaced many more.

A few times a week Pantaleon Joline, 33, brings her adopted daughter Santia Michelle to Pazapa, a centre for disabled children partly funded by the GFC, in the city of Jacmel. Two years ago, she found Santia, then seven months old, abandoned in a hospital. She has Down’s syndrome and hydrocephalus, which causes swelling in the brain. It is impossible not to like her, says Ms Joline, because she is always smiling. But disability is stigmatised in Haiti: Santia’s parents had left her for others to care for. Pazapa, whose name means “step by step” in Haitian creole, was the only place she could go. Thanks to the centre’s support Santia is making progress. She can now sit up straight.

The GFC model goes some way to answering common criticisms of non-governmental organisations and the multibillion-dollar aid industry, sometimes synonymous in public minds with woolly thinking and waste.

Many development projects succeed but “cost a lot of money, and a lot fail”, says Ms Ajmera. “I would rather lose $8,000 on an investment than $50m.” A grant of a few thousand dollars is a small risk but one that can reap big rewards. Working with grassroots groups also speaks to fears that solutions imported from the west rarely succeed. Such groups “are close to communities, they have much more legitimacy, they are more strongly driven by communities they work in”, says Gideon Rabinowitz of the Overseas Development Institute, a think-tank in the UK. “[Foreign NGOs] don’t always have the ability to really, truly understand the needs of the community.”

But the seductive rhetoric of locally generated projects creates its own conundrums. “You can deify grassroots orgs, and assume that because we use the word ‘grassroots’ they reach the most vulnerable,” says Michael Jennings of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. “They will often be staffed by members of a local elite, people with greater income and maybe more educated.” He fears this could create a distance from the people they are seeking to serve.

For Mr Kane, any suggestion that he is not sufficiently “grassroots” rankles. “I don’t come from a rich family,” he says. “I come from a family where connection to the community is very strong. My father and mother taught me that if you have something you should share it.”

The mere act of donation – sometimes necessitating the hiring of staff to keep accounts and submit the reports required by international organisations – can overwhelm a small charity. “There are [grassroots] NGOs that become really popular,” said Ms Ajmera. “If you get too much capital, it can cause you to crash.”

The transformation of an embryonic entity into a fully fledged NGO can also endanger the original small-scale, local spirit. “Often they are temporary, personalised, individual organisations. How do you address that without just turning them into another NGO?” says Mr Jennings.

This does not have to happen, says Ms Lindsey. “The core of what you do can stay the same over time.”

…

For small NGOs, the search for support can become a cynical merry-go-round that frustrates even the most committed activists. Few donors truly consider the strengths of groups with which they work, says Susan Sabaa, executive director at Ghana’s Child Research and Resource Centre (CRRECENT), which promotes child rights and development, and is a candidate for GFC funding. “It looks to me [like] they are interested in dumping their money – ‘we want ABC done’ – and then they come for their report,” she says. “If you don’t look at the strengths of who you are working with, you may not even get results.”

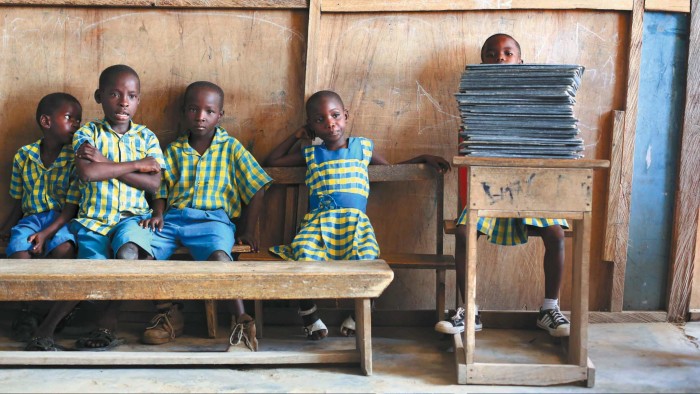

At a school for trafficked children, near the fishing town of Winneba in Ghana’s Central region, the results are there for all to see. Georgina, a shy 12-year-old, sits in the playground in her blue and yellow uniform telling her story. Two years ago, she whispers, her mother took her out of school and sent her to work in domestic service for relatives in the eastern Volta region, hundreds of miles from home. Her father, who is separated from her mother, gave what information he could to an organisation called Challenging Heights, which found her and brought her back.

She is one of hundreds of children the group, whose first donor was the GFC, has rescued from domestic servitude or slavery in the fishing industry. “I was very happy when I came,” says Georgina. “I knew I would be able to go back to school.” Without that initial help from the GFC, says James Kofi Annan, a former child slave who founded Challenging Heights in 2003, the organisation would not have become a leading locally run anti-trafficking group.

The projects the FT visited in Senegal, Haiti and Ghana are small – some scrappy, others ambitious. The future of development could yet belong to them, argues Ms Ajmera. “If you are going to have emerging economies, free-market economies, civil society is extremely important and I don’t believe outsiders can build civil society,” she says.

“There is a place for all of these [aid] groups,” she adds. “[But] over time, in 50 to 60 years, the local organisations would overtake large development groups.”

Comments