Nigerian disrupters aggregate farm plots to boost productivity

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For 45-year-old Ladi Okudu, a smallholder farmer in Nasarawa state, east of the Nigerian capital of Abuja, buying a John Deere tractor with a price tag of more than $30,000 is out of the question. Even if there were tractors available to hire — which mostly there are not — at some $70-$80 per hectare, the rental cost is steep to prohibitive.

Mrs Okudu, who has been farming for 25 years, uses hand tools to produce small quantities of sesame, maize, rice and cassava on her modest plot of land. Like millions of subsistence farmers around Africa, she is stuck in a low-productivity rut that virtually guarantees she will never escape from back-breaking poverty.

The pattern is repeated across much of the continent. The result is that Africa, instead of being a net exporter of food, is a net importer, spending some $40bn a year of precious foreign exchange on basic foodstuff.

Not only is this a waste of resources, say critics of existing policies, it also leaves many at risk of hunger.

That vulnerability has been highlighted by the Covid-19 crisis. Earlier this year India temporarily suspended exports of rice while exports from other countries, including Vietnam and Pakistan, were restricted because of logistical logjams. Muhammad Sabo Nanono, Nigeria’s agriculture minister, has warned that food security in parts of the country could become a serious issue.

Nigeria, which generates 40 per cent of gross domestic product and 60 per cent of employment from farming, normally imports roughly $3bn in food staples.

Last year, the government sought to cut that bill and spur local production by ordering the central bank not to dispense scarce foreign currency to food importers. It also closed its land border to prevent smuggling of cheap imports, especially from neighbouring Benin.

Dimieari Von Kemedi, founder and managing director of Alluvial Agriculture, a Nigerian company that seeks to commercialise smallholder output, argues that this is not the way to solve the problem.

“The larger the number of people involved in primary agricultural production, the less productive that country is,” he says. “So we have gotten things wrong.”

Successive Nigerian governments, he says, have regarded farming as an employer of last resort and have shunned modernisation policies for fear of creating unemployment.

“The belief is that everyone in rural areas in Nigeria should be a farmer and as a result of that we have not fully mechanised, automated and digitised our agriculture,” Mr Kemedi says.

“That has lowered our productivity and means we can’t compete. You can buy rice in India, put it on a ship to a Lagos port, offload it and pay a heavy duty — and it still comes out less expensive than locally produced rice.”

Mr Kemedi says the answer is not to shut out more efficient products from abroad, which will only raise the price for Nigerian consumers.

The key, he says, is to raise productivity. A scheme Mr Kemedi pioneered nearly a decade ago in the oil-rich Delta region, whose wet conditions he describes as ideally suited to rice, has been aggregating small plots of land owned by thousands of smallholders.

By working with farmers on contiguous plots, Alluvial seeks economies of scale in the purchasing of inputs such as seed and fertiliser, and in getting better prices from buyers, including flour mills, rice processors and brewers.

In 2018, Alluvial signed a contract with John Deere and its distributor in Nigeria, Tata Group, to lease tractors to rice farmers in the Delta and Cross Rivers states for as little as 20 minutes.

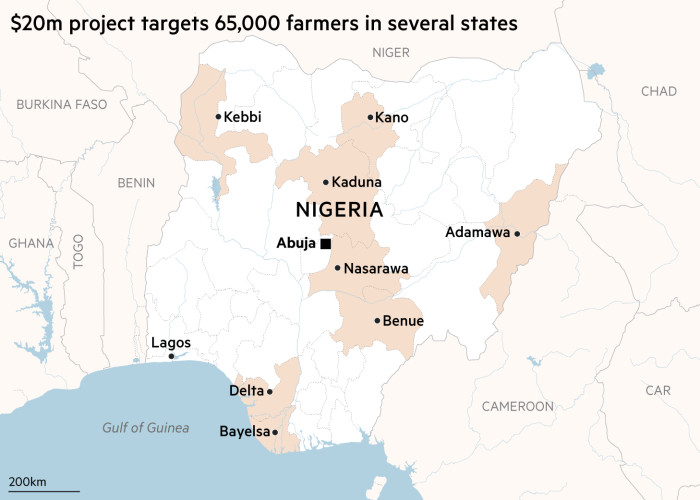

Under a $20m, two-year partnership with the Mastercard Foundation, announced this month, Alluvial hopes to replicate the scheme for 65,000 farmers across the country.

It offers farmers higher-quality seeds, fertiliser and agrochemicals, as well as basic advisory services by phone. Alluvial hopes the extra support will lift yields of rice from 2.5 tonnes per hectare to 4.5 tonnes, and for maize from 1.5 tonnes to 4 tonnes.

The company has chosen plots in states including Adamawa, Bayelsa, Benue, Delta, Kaduna, Kano, Kebbi, and Nasarawa. The idea, says Mr Kemedi, is that by the time Mastercard funding dries up, the projects will be self-sustaining — and scalable.

“This is not proof of concept or just a pilot,” he insists, saying that the model itself has been validated in the Delta. If all the land reached by the Mastercard deal were aggregated, he says, it would cover a landmass equal to 35 per cent of Lagos state.

One of the 65,000 farmers due to be signed up is Mrs Okudu.

She will foot half the bill for tractor hire and a quarter of that for seed imports so that she can establish a credit record that will outlast the scheme.

Mr Kemedi concedes that making progress has not always been easy. In Benue state, where Alluvial has teamed up the Federal University of Agriculture, farmers have not planted anything for five weeks because of arguments over terms. “While they’re arguing they could be making a living,” Mr Kemedi says in frustration.

“There’s a general mistrust, because people have been disappointed too many times before.”

Comments