Walter Chandoha, godfather of cat photography

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“You uncooperative rat,” Walter Chandoha exclaims, midway through our feline farce. The “uncooperative rat”, of course, is not remotely bothered by the complaint, since cats are rarely bothered about doing what humans want them to.

Maddie is not remotely bothered, either, about the cat treats that have been waved at her, or about any of the lip-smacking and “Rrreeeoww, rrreeeow” and “Here kitty, kitty” that we have been using to try to attract her attention and persuade her to pose for a picture with her owner.

Animals: a photography special

An introduction

How pets keep the powerful grounded

Clare Strand faces her fear of snakes through photographs

Ruth van Beek’s new breed of dog

Hagenbeck’s circus: the story behind a 19th-century photo album

Gerrard Gethings’ farmyard animals

Yoshinori Mizutani’s parakeet paradise

Raymond Meeks and Adrianna Ault: at the animal shelter

Mad dogs and Instagram

She is moderately interested in the expensive-looking embroidered scarf we wave under her nose — “You don’t mind if this gets scratched up, do you?” Chandoha asks his daughter Chiara, who gamely replies that she does not — but we are ultimately unable to convert the animal’s sporadic lunges for the scarf into an affectionate pose. After several rounds of dragging Maddie, scuffing and biting at the material, across the drawing-room floor, Chiara takes a mis-step backwards and treads on the cat’s tail. With a yowl, Maddie flees upstairs, and we give up, empty-handed for now.

“You see what I go through,” Chandoha says — and my goodness, we do.

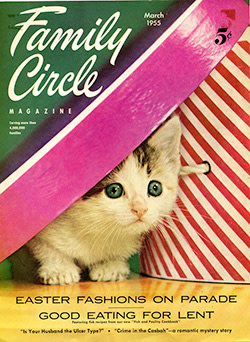

Long before the internet was built on a bedrock of cat pictures, ad execs and magazine editors knew that a well-staged photograph of a cute kitty could boost sales, and no one was employed more often to stage these glamourpuss shots than Walter Chandoha. That he did so before the rapid-fire of digital cameras only makes his achievement more remarkable.

In a career spanning more than four decades, his cats appeared on hundreds of magazine covers and in thousands of advertisements for everything from department stores to bras. Walking the supermarket pet-food aisle in the 1960s was like attending a Chandoha gallery opening; almost every brand used his work on its packaging at one point.

He is 96 now — although his cheeky grin and full head of white hair make him look a couple of decades younger — and enjoying a resurgence of interest in his work, and his method. Last year’s glossy book, The Cat Photographer, showcased his signature style of portraiture, in which he backlights his models so intensely that every last hair stands out. They are stately pictures, in bold colours.

It is not hard to imagine why one shot in particular is his favourite: five kittens in a neat row, each with a vivid, playful expression, two of them smilingly pawing each other. After our experience with Maddie, the idea of herding five before a camera is unfathomable.

“You’ve got to have patience,” he says. “Sometimes you know what they will do, but you have got to wait a long time for them to do it.”

It started with a stray, a shivering little grey kitten that Chandoha found abandoned in the snow in New York, where he was studying marketing on the GI Bill after the second world war.

He named him Loco — for a reason that remained a mystery, the animal would run around like a mad thing every night at 11pm on the dot — and quickly found that he was more likely to win lucrative photography competitions in local magazines and newspapers with Loco’s charming antics than with any other subject.

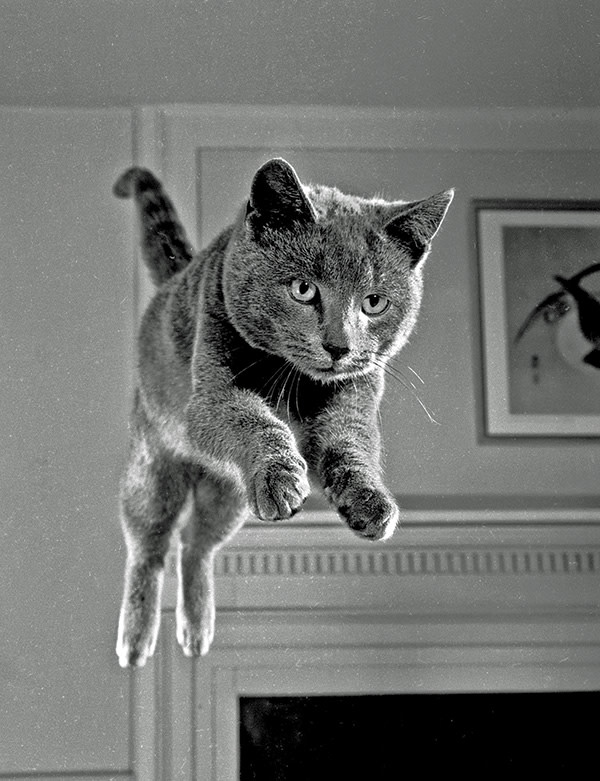

It was with Loco that he would experiment with how to get his subjects to behave; for example, enticing him to jump for the camera by placing food on a series of strategically placed stools. Later, he would borrow basket-loads more kittens from the abandoned litters at the Greenwich Village Humane Society, picking out those that seemed the sparkiest, the most expressive or the most responsive to his coochy cooing.

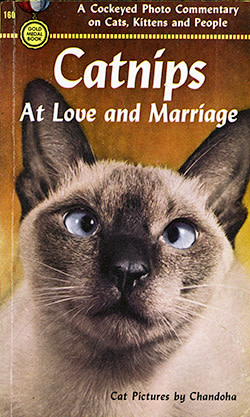

Soon there was enough interest for a book, the first of dozens. Catnips at Love and Marriage, from 1951, was a kind of proto-BuzzFeed in paperback, pairing cat pictures with tongue-in-cheek (and very of its time) relationship advice. “Don’t be a cold wife,” it says below a picture of a scowling animal on the opening page.

On the next, under a cat turning tail: “ . . . or his affections will wander.”

There are lots of tricks in this trade: a rub of bacon on a kitten’s ear will encourage the mother cat to lick it; a smear of mayonnaise on a cat’s lips will make it lick its chops; separate “the crybaby of the litter” from its siblings and the mother will run to pick it up in her mouth and carry it back to the basket.

It is not picture-perfect unless the cat is looking directly into the camera, he says. “I would start barking, meowing, hissing, squawking, whatever it takes to get their attention. It would sound like a barnyard when we were shooting.”

But Chandoha gave up the staged studio work after his beloved wife Maria died in 1992. She was a kind of cat-whisperer, soothing the animals until, from the lessening of tension in their muscles, she could be sure they were placid enough for him to take his pictures. In later years, he turned his lens to gardens, taking exquisite care to learn how to grow the plumpest tomatoes or the sturdiest ornamental grasses before even beginning to frame his pictures.

Retirement? No such thing. He is still repurposing his old work, and pitching ideas to magazines with the enthusiasm of an early-career freelancer. A couple of years ago, The New York Times published his pictures of the old Penn Station in Manhattan, taken shortly before it was torn down and replaced with Madison Square Garden in 1963.

And the ideas are still coming thick and fast: he hopes to publish another collection of his cat photography, a book of nonsense rhymes illustrated with his work (“There’s nothing sillier/Than a romantic gorill-i-a”), and a compendium of pictures and tips for small gardens. He is also turning over in his mind a magazine feature pairing photographs of apes with outrageous statements from the mouth of Donald Trump. “I call it ‘Trump Verbatim’. Here’s one of a gorilla beating its chest,” he says, pulling a black-and-white shot from a folder. “That would be a good one to use.”

***

We do not plan to give up without our shot of Chandoha and Maddie, so it is off to the couch for another round of calling, cooing and cajoling.

Once again, it seems we may be doomed. Our photographer, Jody, has loaded a fresh roll of film and is ready to shoot when Chandoha’s cane slips and hits the floor with a bang, sending the cat scooting. But a tickle under the chin, a stroke down the back, a scratch of the head and we have it: Chandoha, the godfather of cat photography, and his cat. Patience, as predicted, gets its reward.

“That is where I differ from the pictures you see on Facebook or Google,” he says. “The pictures there on the whole are superb but they are a one-shot thing. Could the photographer repeat that time after time after time? Could he do a variation on that? The answer is no, because most of them are just lucky shots.”

Stephen Foley is the FT’s US investment correspondent. ‘Walter Chandoha: The Cat Photographer’ is published by Aperture (£19.95; $29.95)

Portraits of Walter Chandoha by Jody Rogac, ACN Studio; all other photography Walter Chandoha

Comments