China’s Comac reliant on ‘captive domestic market’ for sales

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When China’s ruling Communist Party released its 14th five-year plan in 2021, chief among its aims was “self-reliance in science and technology as a strategic underpinning for national development”.

But a year later, experts say the continued wait for delivery of the single-aisle C919, China’s first passenger jet, is a reminder that the country’s civil aviation industry is “decades” behind the west and remains heavily dependent on western suppliers.

“The jury is still out on whether China can develop an internationally recognised and successful aerospace industry,” says Sash Tusa, aerospace and defence analyst at research firm Agency Partners.

The C919 was due at the end of last year. No date for delivery has been set though in May the first test flight of an aircraft that is set to be delivered was completed. The jet is being developed by the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (Comac), a state-backed group spun out from China’s military.

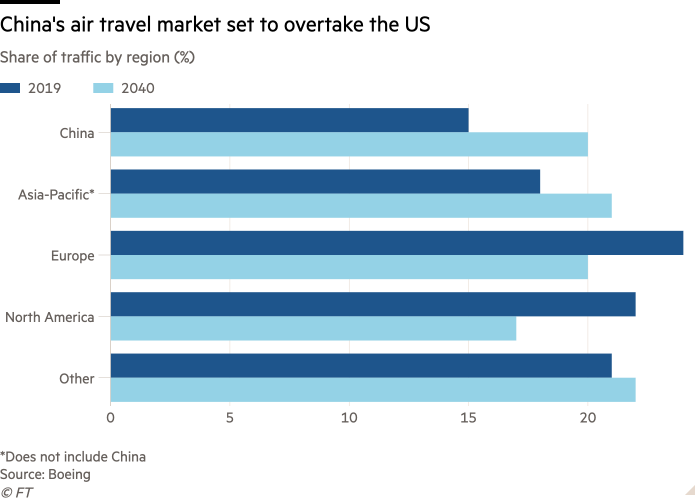

China is set to become the world’s largest market for air travel and has 248 operational airports, according to the Centre for Aviation.

It is now one of the two most important markets for the two global aviation giants Boeing and Airbus. Boeing forecasts that one in every five commercial aeroplanes ordered between 2021 and 2040 will be for customers in China.

At the start of this month, Airbus announced a deal with four Chinese airlines for 292 single-aisle A320 aircraft, which carry a ticket value of $37bn. But according to Jim Harris, who leads the aerospace and defence practice at Bain & Company, Comac will end the Boeing-Airbus duopoly in China for large commercial aircraft before 2040.

“The Chinese government is willing to invest tens of billions of dollars to achieve this strategic outcome, and China provides a large captive domestic market in which Beijing can mandate orders for Comac even if the C919 is less competitive than western alternatives,” he says.

Analysts estimate that development of the C919 has been backed by between $50bn and $72bn in state-related support, compared with the $22bn that the World Trade Organization says Airbus received for the A320 and other models.

Comac has so far received 815 orders from 28 parties for Rmb500bn ($74bn) according to its website, almost all believed to be from Chinese domestic airlines such as China Eastern Airlines and Shenzhen Airlines.

The group aims to control one-third of the Chinese domestic market for large aircraft by 2035. An Airbus report from 2018 forecast that the Chinese domestic market would need 7,400 additional aircraft by 2037.

For the global market, however, industry insiders say that the 168-seat C919 is not as competitive as it is less fuel efficient than Boeing and Airbus jets and will struggle to attract international buyers away from the two groups.

Airbus says that while it expects “some part” of China’s domestic demand to be met by C919s, internationally Comac lacks the infrastructure and investment to be a threat to the Airbus-Boeing duopoly.

For it to achieve wider market success Comac would need “an international sales organisation as well as an established customer support network. Indeed, it took Airbus some 40 years to achieve parity with the US manufacturers,” says the company.

The C919 also shows how far China is from developing a fully native aviation supply chain, leaving it exposed to geopolitical risk. It relies on western companies to produce its most complex parts, including the engine, which is the product of a joint venture between America’s GE and France’s Safran.

This means that even though the plane, and many of its parts, are manufactured by Chinese assembly lines, the company depends on intellectual property and aftersales services from western companies.

Tusa says Beijing has had an instructive lesson on what would happen if relations with the west soured, from witnessing the sanctions that crippled Russia’s aviation industry by withdrawing the western expertise and supplies of spare parts.

“To take a C919 and turn it into a Chinese-only aircraft would require redesign, testing of every single certificate, most important of which is the engines. I’ll see you in the late 2030s,” he says.

Comac has already been squeezed by US-China tensions. It was put on a Trump administration watchlist in 2021 over its alleged military links, although the Biden administration removed it months later.

Geopolitical tensions around China are also a concern for western suppliers. Harris from Bain warns they “will need to walk a fine line between capturing growth opportunities in the China market versus enabling a future competitor”.

Comments