Morocco tourism struggles despite vaccine progress

Simply sign up to the Travel & leisure industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The pandemic hit Morocco just as bike tour company Marrakech Green Wheels was entering its peak season in the spring, when the heat is less harsh. Everything was cancelled and the company has not had a single booking or a penny of revenue since. Now, founder Adel El Filali has stopped waiting for tourists to return.

“Forget about tourism until it is back, you can’t rely on it at all,” says the 31-year-old, who has started working in fashion production, while his co-founder works in a call centre. Instead, they have been active in organising cycling activities for locals on a voluntary basis.

Morocco’s orders are open and vaccinated visitors are exempt from quarantine but, in the Marrakesh old town, many restaurants and shops have yet to reopen their doors because footfall remains low.

The toll of the pandemic on tourism, which, according to the World Bank, contributes 11 per cent of the country’s GDP and accounts for 17 per cent of the workforce, was felt both locally and nationally.

While other sectors of the economy are starting to rebound, tourism will “continue to suffer”, says Yasmina Abouzzohour, research fellow at the Harvard Middle East Initiative. Back in 2020, she warned that “banking on the tourism sector to accelerate economic recovery will lead to disappointing results”.

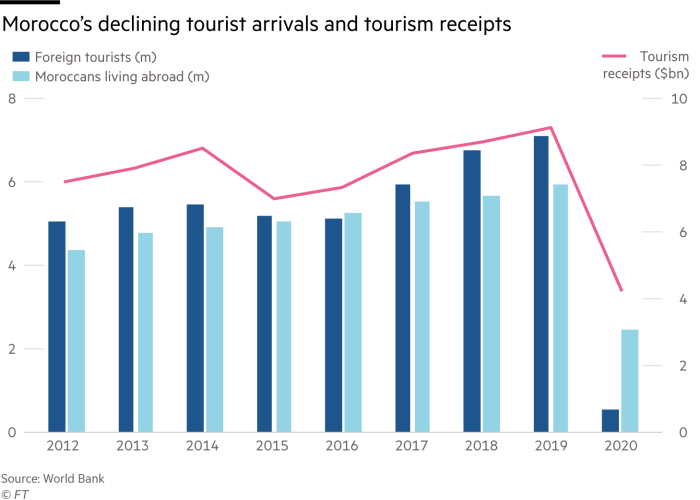

A more than halving of tourism revenues in 2020 was an important factor in the country’s recession — its first since 1995. Overall, Morocco’s GDP declined by 6.3 per cent during 2020, according to Capital Economics and, while the IMF says growth is expected to accelerate to 4.5 per cent in 2021, the services sector is projected to lag behind.

Morocco started prioritising tourism as an economic sector in the early 2000s. Just before the pandemic in 2019, foreign tourist arrivals were at 7m people, compared with 2.2m in 2002. But, in 2020, tourist arrivals fell by 78.5 per cent. The National Federation of the Hotel Industry predicts 2021 will be worse than 2020 for the sector overall.

Despite the slow recovery, “the recently disclosed New Development Model [the country’s social and economic strategy] emphasises tourism as a strategic sector”, says Javier Díaz Cassou, an economist with the World Bank. He adds that tourism received extensive public support.

Workers in the tourism sector were eligible for 2,000 dirhams (€200) a month from the government. However, the fact that many workers do not have a contract, along with other administrative issues, has meant that many people fell through the cracks — and, in any case, the sum would barely cover rent in Marrakesh.

“They stopped paying [in July 2020] and said ‘open the restaurants’ — but for which clients?,” recalls Rachid Joualla, 49, a waiter at La Tanjia restaurant, which currently receives 30-40 guests a day, compared with around 200 before the pandemic.

As bookings and visitor figures plummeted, Marrakesh-based social media influencer Yasmina Olfi, who posts about travel, saw an increase in her Instagram following and in invitations from hotels across the country.

More from this report

Pandemic exposes vulnerabilities in Moroccan economy

Morocco’s carmaking prowess a result of shrewd state planning

Critics flag opposition weakness in Morocco’s new parliament

Morocco asserts its power as diplomatic spats simmer

Moroccan lenders shore up small businesses but risks loom

Casablanca financial hub’s fortunes tied to national economic strategy

“People who couldn’t travel to Morocco would travel vicariously through my journeys,” she says. She sometimes promoted places for free as “it was a duty for people who have a large community to showcase beautiful places and encourage local tourism”.

But this hasn’t translated into real-life experiences. Hundreds of Riads — traditional houses that have been converted into boutique hotels — have gone without bookings for more than a year.

The Riad Dar Zaya in Marrakesh was hit with large-scale cancellations in August after the government reintroduced a 9pm curfew, says Yassine Alaatchane, the hotel’s manager. “The government asked Riads to give discounts for local guests, but Moroccans don’t like old houses because we know these houses.”

Morocco is hoping that tourism will benefit from the normalisation of relations with Israel, says Riccardo Fabiani, north Africa director for the International Crisis Group. On July 25, 2021, the first direct flight flew from Tel Aviv to Marrakesh, carrying 100 passengers.

“The flight was hugely talked about,” says Fabiani. “They are hoping to capitalise on flows of Moroccan Jews coming back to their ancient old homes and sanctuaries.”

But, in the Marrakesh Mellah, the Jewish quarter, the blue-and-white-tiled courtyard of the Slat al-Azama Synagogue is empty and local market sellers have not seen any more tourists than usual.

“A couple of groups came this year,” says Abdul Boussabir, a 54-year-old spice seller, who closed for months during 2020. “But Moroccan Jews have always come here. It’s the same as before, [or] even less.”

Bike enthusiast El Filali tries to stay optimistic. “This is not the first time Marrakesh has lost tourists,” he says, referring to a 2011 terrorist attack that killed 17 people in the main city square, Jemaa el-Fnaa. “It will pick up, but this is a long one. Even with the vaccine, things are still not moving.”

Comments