Misadventures in bondland

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Bill Gross’s typically acerbic views on the lack of returns from Total Return bond funds like the one he used to manage at Pimco got us thinking about one one-time rival of the “Bond King”: Michael Hasenstab.

Franklin Templeton’s Hasenstab made his name through massive (and we mean massive) bets on struggling counties like Ireland, Hungary, Ukraine, Argentina and Ghana, utterly eschewing the confines of indices or traditional bond fund styles. As he wrote in the FT back in 2014:

. . . while equity investors have long recognized the need to go global and add to returns and better diversity risks, fixed income investors are still at the initial stages of internationalizing their portfolios. So while there is much talk about “the great rotation” from fixed income to equity or vice-versa, we actually think the more interesting rotation is from traditional core fixed income to unconstrained global. This is especially true since the ability to generate positive returns in core fixed income markets is pretty limited given historically low rates.

Some of these wagers worked out (he made a killing in Ireland and Hungary, and managed to eke out a profit from Ukraine despite the 2014 invasion), and others did not (Argentina turned out to be a nightmare).

But what really hurt him in recent years — and deflated the size of his Global Bond Fund from a peak of $73bn less than a decade ago to just $5.8bn today — was a mammoth bet against US Treasuries, and developed market bonds in general.

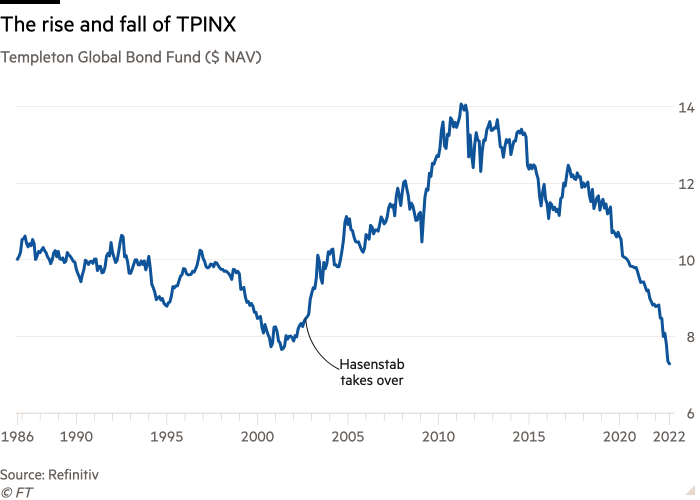

For a few years, the Templeton Global Bond Fund even had negative duration — in practice, it would make money if interest rates went up. Instead, the bond market kept humming, and Hasenstab’s flagship fund wilted. Here you can see how TPINX’s net asset value has waxed and waned over Hasenstab’s two-decade reign.

You’d think a sour view of developed bond markets would have served him well in 2022, with duration clobbered by rising interest rates. Finally, years after saying investors should flee the illusory safety of high-grade sovereign debt, Hasenstab should be vindicated? Right?

Unfortunately, the market gods are cruel.

Because of the long string of bad results, Hasenstab in 2020 closed out his Treasury short, and last year committed to keeping the Templeton Global Bond Fund’s duration at least in positive territory. Whoops.

At pixel time, Morningstar says the fund’s effective duration is 1.79 years, so it still exceptionally low compared to most of its peers. As the Morningstar snapshot below shows, this has kept the fund’s losses a little contained at 14.2 per cent so far in 2022, compared to the 18.7 per cent average loss of similar bond funds, and a savage 22 per cent drawdown for their benchmark.

But lets face it, merely losing 14 per cent isn’t exactly great either.

This is not to cast shade on Hasenstab, who is one of the more cerebral and genuinely thought-provoking bond fund managers this FTAV writer has met.

But this shows once again — if anyone needed reminding — just how hard it is to run money. Often you can even get the basic thesis right, and still lose money by being too early (or tarnish an entire career if you’re far too early) And given how fickle markets are, you just know that as soon as you’re forced to close down a position, it’s going to come good right afterwards.

On the plus side, there’s a ton of the kind of turbulent sovereign debt market that first made Hasenstab’s name over a decade ago emerging again right now. And if the dollar’s strength fades, then TPINX’s big bets on local-currency debt in Asia and parts of Latin America could do well.

Hasenstab and his co-manager Calvin Ho wrote earlier this month that these have been “battle tested” in previous crises, and are in much better shape than the developed world.

Many emerging markets have periodically dealt with high or double digit inflation, sharply rising interest rates and falling exchange rates over the past few decades. Emerging markets that have suffered through the various crises have often learned from the pain of the past, leading them to a path where their corporations can manage foreign exchange denominated debt, governments can manage fiscal policy and central banks can manage monetary policy appropriately, allowing them to weather such developments in a relatively sanguine way. In fact, some emerging markets were so proactive with monetary policy tightening when inflation pressures began building last year that they are already at or near the end of those cycles. By contrast, developed countries have enjoyed a long period of stability with low inflation, until the past year. In general, they haven’t seen any significant inflation since the 1970s or early 1980s, and navigating policy around these rates and their effect on expectations is proving tricky.

We will see.

Comments