Austria’s tax and legal reforms hang in the balance

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The conservative-led coalitions that have governed Austria since December 2017 have presided over one of the most turbulent periods of political experimentation in the country’s post-1945 history.

From a business perspective, however, the outward impression of instability can be misleading. Through a series of tax and corporation law reforms that promise to reshape the commercial landscape, the government, led by the Austrian People’s party (ÖVP), is trying to improve the nation’s competitiveness and attractiveness as a destination for foreign investment.

The centrepiece of these efforts is a tax reform plan unveiled on October 3, just eight days before Sebastian Kurz resigned as chancellor after he came under investigation for suspected corruption.

In early December, Kurz said he was quitting politics — an announcement that triggered the resignation of Alexander Schallenberg, his shortlived successor as chancellor, and the appointment of former interior minister Karl Nehammer in Schallenberg’s place.

The tax reforms are contained in a 2022 budget proposal whose passage through parliament will require the survival of the coalition that Kurz put together in January 2020, between the People’s party and the Greens.

So far, this conservative-Green coalition, the first of its kind in Austria, has shown considerable resilience in power.

No sooner had it assumed office than it was battling with the Covid-19 pandemic. Now, it is grappling with the scandal that engulfed Kurz.

Kurz and nine other individuals are under investigation for bribery over allegations that finance ministry resources had been used between 2016 and 2018 to manipulate opinion polls measuring the popularity of political parties. Kurz has denied any wrongdoing and no charges have been brought.

But even if the coalition fails to last for a five-year legislative term, up to the next scheduled parliamentary elections in 2024, it appears determined that the tax reforms will take effect. For businesses, the highlight of these reforms is a proposal to cut the corporate tax rate from 25 per cent to 24 per cent in 2023 and to 23 per cent in 2024.

However, the coalition dropped earlier versions of the plan that foresaw a cut to 21 per cent by 2024.

To some degree, this reflected the government’s firm view that Austria and other eurozone countries should return as soon as possible to fiscal discipline after the extraordinary expenditures adopted in the pandemic. According to the finance ministry, discretionary measures related to fighting the Covid-19 crisis amounted to €24.7bn as of July 15 — or the equivalent of 6.6 per cent of gross domestic product in 2020.

Some tax specialists think that, despite the importance of sound public finances, the government should have stuck to its first, more radical tax-cutting plan.

“Austria should not shy from lowering the corporate income tax rate sooner or even implementing a more ambitious tax reform to improve its tax competitiveness and contribute to greater economic growth,” says Cristina Enache, an economist at the Tax Foundation research group.

There are other pro-business measures in the 2022 budget, though.

The tax-exempt portion of the first €30,000 of annual profit will be raised from 13 per cent to 15 per cent. And depreciable property, plant and equipment with a value of up to €1,000 will be classified as low-value assets that can be completely deducted as operating expenditures — right now, the threshold is €800.

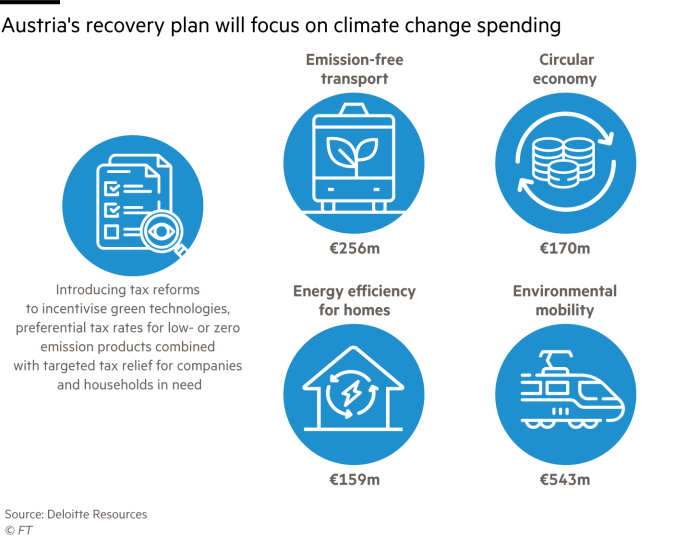

The budget also shows how Austria’s tax policies are increasingly being shaped by a commitment to the EU’s green transition agenda. Starting from next July, carbon dioxide emissions will be taxed at €30 a ton. This will rise to €35 in 2023, €45 in 2024 and €55 in 2025. To offset this rising tax burden, the government is preparing an investment allowance of up to €350m to help businesses raise their energy efficiency.

The ruling coalition is trying to build on earlier initiatives aimed at improving the business climate. In September, several changes to Austrian competition law took effect. Under one, corporate mergers do not need to be notified to the competition authorities unless at least two of the businesses concerned have a turnover of €1m or more in Austria.

At the same time, the government has tweaked the powers of Austria’s Cartel Court, which oversees mergers. Previously, the court could approve deals that might lessen competition if it decided they were necessary to maintain or improve the companies’ international competitiveness, if the larger macroeconomic picture justified the them, or if the deals improved the general conditions of competition enough to outweigh any negative impact.

Now, the court can approve a merger if its macroeconomic advantages “significantly” outweigh any negative effects.

According to Wolters Kluwer, a tax and accountancy firm, these changes are “expected to lead to a significant reduction in the number of transactions requiring notification in Austria”.

The IMF, in its latest review of the Austrian economy, in September, suggested other pro-business reforms would be possible, even with the government’s emphasis on fiscal prudence.

“Austria still has fiscal space . . . to implement additional measures to boost the recovery, such as by providing solvency support to viable firms, added investment in green initiatives and digitalisation, further steps to lower the labour tax wedge, and active labour market policies to address skills and regional mismatches in the labour market,” the IMF said.

In the near term, however, the focus of investors will be on how long the conservative-Green coalition will stay in office.

Comments