Brexit triggers a great car parts race for UK auto industry

Simply sign up to the European companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

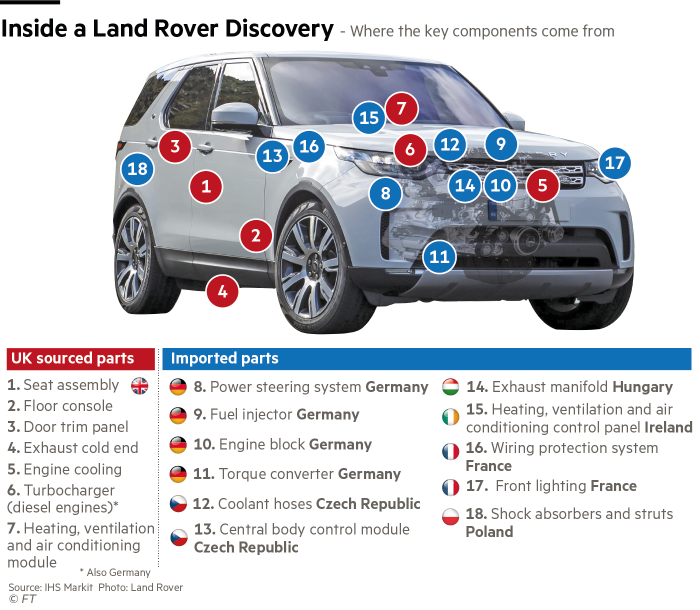

If you drive one of the 1.7m cars built in the UK last year it is likely the power steering on the vehicle was manufactured in Germany; the electronic control units came via Romania; and the shock absorbers travelled all the way from Poland. Indeed, more than half the 30,000 components in an average British-made car come from somewhere else.

Until June 23 last year that represented a triumph of modern supply chain logistics. Now, with the UK leaving the EU, it is less a marvel and more a problem.

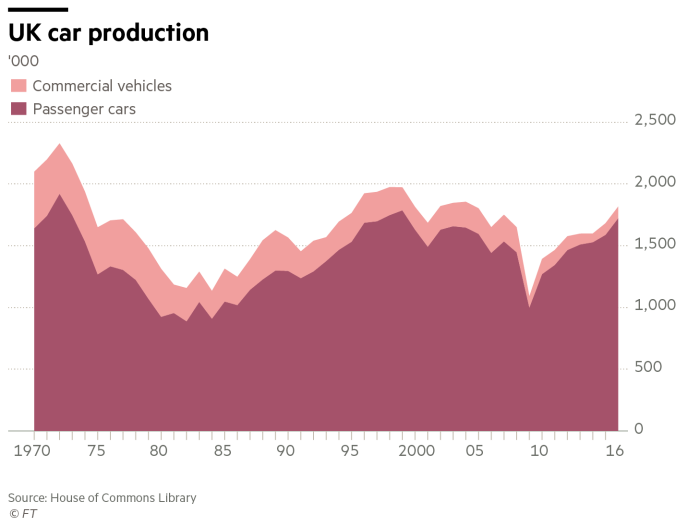

The auto sector, which employs more than 800,000 people in the UK with 170,000 in manufacturing roles, is one of the most important tests of how Brexit will impact British industry. Under trade rules that the UK is likely to face after it leaves the EU, British auto exports could attract hefty tariffs if carmakers are unable to source a far higher proportion of the components going into the average Nissan, Honda, or Vauxhall from within the UK.

“World Trade Organisation rules would mean a 10 per cent tariff on vehicles and an average 4.5 per cent tariff on components,” says Mike Hawes, chief executive at the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, the industry body. “The cost of our production would increase more than our competitors. British competitiveness would be undermined. The cost of cars for British consumers could increase.”

While the supplier base has expanded in recent years, UK automakers still rely on the EU. “We have a huge dependency on Europe,” says Ralf Speth, chief executive of Jaguar Land Rover, Britain’s largest carmaker. “You simply can’t buy some components in the UK.”

Nissan earlier this year invited a large group of international component manufacturers to its UK base in north-east England and made a simple pitch: please come to Britain. In the wake of Brexit the Japanese carmaker had received assurances from the government that its operations would be insulated from its worst effects and it had responded by committing to make its next generation of sports utility vehicles at its Sunderland assembly plant.

Senior executives from the company and even the UK trade minister Mark Garnier were on hand to answer questions from the suppliers, who ranged from metal bashers to intricate component makers. What Nissan started others, including Jaguar Land Rover, Toyota, Vauxhall and BMW’s Mini, replicated giving birth to a concerted nationwide effort to rebuild the UK’s automotive supply chain.

In theory, Brexit presents an opportunity to spur UK production of components, providing a boost to the industrial base and the broader economy. But if those efforts fall short, UK car plants could become much less competitive.

In an announcement that the British government called a “vote of confidence” in the UK, BMW said last week that it would build the first electric Mini in the UK from 2019. However, in a sign of the broader dilemma for the industry, the battery that will power the car will be manufactured in Germany.

Drop in investment

Nissan, which exports 55 per cent of its UK production to Europe, has been at the forefront of efforts to attract new suppliers to Britain, but it has also sounded the alarm about Brexit. Colin Lawther, the carmaker’s European manufacturing director, told MPs on a select committee in February that the Sunderland plant “will not succeed in the future, with or without Brexit, unless the government does something to help us in the supply chain”.

He asked for a £100m fund to help carmakers relocate parts-makers to Britain. MPs asked whether, without the money, the Sunderland site was safe. “No,” he added. “I wouldn’t say that.”

The uncertainty around Brexit has already taken its toll on the industry. Investment in the auto sector fell from £2.5bn in 2015 to £1.66bn last year, and has slid to just £322m in the first six months of 2017, according to the SMMT.

It warned last week that UK car production could drop 10 per cent if Britain does not secure a transitional deal to allow the industry to carry on trading with Europe after Brexit, while the full terms of a trade deal are agreed.

While UK components once accounted for 80 per cent of parts in British-built cars, the figure fell to the low 30s during the 1990s and early 2000s. But it has been slowly climbing again, rising to 44 per cent this year, according to the Automotive Council, a collaboration between government and the private sector.

Brexit is now providing new urgency. Once Britain leaves the EU, it must forge its own free trade agreements that allow it to sell goods to other nations without incurring costly tariffs. But FTAs typically stipulate that cars must contain a certain percentage of components from the country of manufacture, under “rules of origin” regulations. Experts believe that for the UK that could mean at least half of all parts will need to be sourced domestically.

Of those 30,000 components in modern vehicles, each one may contain 30 sub-components and have passed through 15 countries during the course of its production, according to Clepa, the European supply chain organisation. With many of the parts going into Tier One components coming from overseas, it is therefore highly likely that the true UK make-up of vehicle components is far lower than 44 per cent, making the gap to be bridged even larger.

Without clearing the parts threshold, the cars made on British production lines would be subject to WTO tariffs of 10 per cent — making them much more expensive. An obvious solution would be to force carmakers in the UK to buy from domestic suppliers. But in many cases, the parts are not available.

Land Rover, which has annual production touching 600,000 vehicles, buys 40 per cent of its materials from Europe. For the recent launch of the £60,000 Range Rover Velar it convinced a French bumper company, Plastic Omnium, to set up operations in Britain, with the promise of work supplying other models in its range.

But such an arrangement cannot be replicated with more complex parts. From alloy wheels to in-car electronics, many of the components are difficult to build at scale in a market where vehicle output is less than one-third of the size of Germany, which produces 6m a year.

“It’s not like you could do everything in the UK,” says Nigel Stein, chief executive of British manufacturing group GKN. “In today’s economy you have to have economic scale and you’re not going to have it in every country in the world.”

In 2014, the Automotive Council drew up a list of the supply chain elements that the UK could attract. It featured engine castings, the metal frame for a car’s engine, as well as seat components, alloy wheels, lighting, paint, bumpers and instrument clusters. A new government body, the Automotive Investment Organisation, was set up to attract new plants. The courting process to woo suppliers can last from months to several years, and typically involves meeting a senior government minister, a tour of a UK car facility and dinner in a private room at the Royal Automobile Club on Pall Mall.

Wooing suppliers

The UK has enjoyed some success. Investments of more than £2bn have been made in the past three years, while a number of items, such as exhausts, have fallen off the wish list as suppliers have set up business in the UK.

Mr Garnier, the UK trade minister, believes post-Brexit Britain will still be able to attract significant investment. The country’s legal system, as well as its motorsports heritage and research and development, make it an attractive destination, he says, but admits Brexit poses a “challenge”. “We cannot try to say this isn’t an issue when it comes to the European stuff, it would be lying,” adding that Brexit presents “a great opportunity” to rebuild the supply base.

Many key areas of the chain are still lacking in the UK. Forging, the manufacturing process by which metal is shaped into parts under force, is a prime example of how the UK supply chain has been hollowed out.

In the mid-1970s, the industry churned out around 500,000 tonnes of forged parts each year, with 60 per cent going into passenger cars, commercial vehicles and off-highway equipment such as diggers, according to the Confederation of British Metalforming. Today it is just 130,000 tonnes, with less than a fifth destined for cars.

Although some smaller forged car parts are made domestically, there are no large presses dedicated to passenger car crankshafts. Existing British sites that service the aerospace, trucking and mining industries could not easily be re-purposed for the task.

Ken Campbell, forging specialist at the CBM, says: “You would need to have new plant”, with a dedicated line producing crankshafts for cars. This would cost “tens of millions” — spending that is hard to justify without a strong commitment from customers.

Another gap is in alloy wheels, despite the feature being one of the most popular additions to new cars. The country’s only significant producer, Rimstock, caters for the high-end market of supercars and racing vehicles.

“Making wheels is fairly simple, but it takes a lot of investment to do it right,” says chief executive Stephen Lane. Any UK plant catering for mass-market vehicles would require £200m of investment and need to make at least 2m wheels a year to be viable, he says.

Rimstock is ramping up production to produce 650,000 wheels a year. But it has no plans for mass-market expansion. “We’ve looked at it, we’ve cost checked it,” he says. “It’s just too much of a stretch for us.”

Electronics gap

Electronics, an increasingly important function in modern cars that use software to dictate features from steering assistance to WiFi connection, is a gaping hole in the supply base. Electronic control units, the brain of the car’s infotainment and navigation system, are made in low-cost markets and shipped all over the world. In Europe, they tend to be assembled in Romania, where labour costs are a fraction of the UK.

“Regardless of whether you are Fiat in Italy or Jaguar Land Rover in Halewood you’re buying from [eastern Europe],” says Matteo Fini, an analyst at IHS, who specialises in the auto supply chain.

Some parts have to be made locally because they are so heavy. “If you supply a large body panel, you need to be very close because logistics costs will kill you,” says Francisco Riberas, chief executive of Gestamp, the Spanish metal stamping company. “It has to be local.” The group confirmed a £70m investment in a new UK pressing plant shortly after the Brexit vote.

For some small businesses, the push to buy more British parts has led to a boom in orders. Yet others remain reluctant to gamble on major expansion to sell directly to the volume carmakers, which push their suppliers hard.

Under “just in time” processes, parts arrive at a plant just hours before being fitted on to vehicles, with delivery windows as tight as 10 minutes. “If you miss a delivery the lines stop,” says the manager of one UK plant. “You’ve got to be on your game.”

Comments