Retirement savings: how much is enough?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Sweeping reforms to retirement savings rules this year have put pensions in the spotlight, but half of UK workers still have no idea how much they have saved into a pension scheme, according to Aegon, the Dutch life assurer.

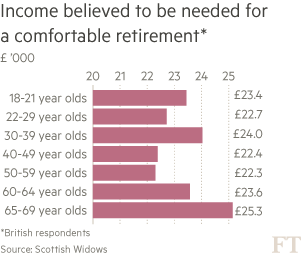

And the affluent are not immune to a lack of interest: among those earning above £50,000 a year, people with more opportunity than most to save for the future, almost four in 10 are still not saving enough for a comfortable retirement, according to a Scottish Widows report.

For many, part of the problem is knowing where to start. Does saving begin with imagining the retirement you would like, even if it is 30 or 40 years away, and setting your target accordingly? Or is it better to start with how much you can afford to set aside now?

Here, we talk to experts about how best to start, plan and grow retirement savings at every stage of working life.

1. Make a start

“For most people, it’s probably sensible to start from your current income and look forwards,” says Patrick Connolly, a chartered financial planner at Chase de Vere, who warns against frightening younger savers into inertia with daunting and big numbers. “It can be very difficult to judge how much you will need in retirement and for younger people there’s a risk they will overestimate that and be terrified by the amount they would need to save in order to reach it.”

While savings depend on circumstances, Mr Connolly says that 15 per cent of a salary, including employer contributions, is an “ideal” starting amount for earners at any age.

Scottish Widows, meanwhile, puts “adequate” at 12 per cent. These proportions assume savers are members of a defined contribution pension scheme, in which retirees buy an annuity or take income drawdown based on the total sum they have saved during their working years, rather than of a defined benefit scheme, which guarantees a retirement income based on factors such as final salary and years worked.

How might workers adjust those proportions as they reach mid-career? “Effectively in your 20s and 30s you can focus on what you can afford to put away, in your 40s and beyond, look the other way around — what is this going to get me on target to hit?” says Mr Connolly.

Richard Parkin, head of retirement at Fidelity Worldwide Investment, says a useful trick is to increase the percentage you save each time you receive a pay rise, an option now offered to some US workers under a formal “auto-escalation” system.

2. Keep track

The next hurdle is calculating the lump sum you are on track to save. Online calculators from pension providers such as Standard Life can offer an estimate if you enter in variables, such as the value of your current pension pot, your age and your present salary. But the results are guesses because the real outcome will depend on how investments will fare in future.

Research by Altus, a consultancy, found that predicted pension pots under the same savings scenario varied between such calculators from £115,000 to £370,000 because their results were based on assumptions.

Podcast - FT Money Show

Future of retirement: How much do you need to save?

The FT’s Judith Evans invites experts to offer advice to a twentysomething on getting started with a pension fund

However, online calculators become more useful as a saver approaches retirement, when there are fewer variables left to affect the outcome, Mr Connolly says.

3. A professional action plan

How does a lump sum become income? That has become a more complex question since April’s rule change gave savers more freedom over their pension pots. Those over 55 are now allowed to withdraw cash lump sums from defined contribution funds or opt to keep their savings invested, rather than being forced to buy annuities, which have plummeted in popularity since.

Mr Parkin says his company starts by outlining annuity rates, which are often dauntingly low, when meeting clients for the first time.

“With annuity rates as they are at the moment, we are effectively giving a worst-case scenario without making assumptions about someone’s appetite for risk or their capacity to take loss. We are erring on the side of caution,” he says.

For example, £100,000 will currently buy a 60-year-old an annual income of £5,131, according to figures from Hargreaves Lansdown.

However, actual rates depend on the type of deal buyers choose, for example they can buy annuities that will pay out to a spouse after death, and annuity rates change over time.

While annuities are still a useful reference point, retirees can now choose between options that include living off investment income and gradually drawing down capital. Each option affects what income level is achieved from a lump sum, but choosing what strategy to adopt requires professional advice.

4. Consider tax

For wealthier savers with substantial pension pots, there is another consideration: the lifetime allowance, which limits pensions tax relief and has been cut from £1.8m to £1.25m over five years. It will fall again to £1m from April 2016.

Current savers have a limited opportunity, therefore, to protect existing pensions from taxation above this limit. For those further from retirement, the lifetime allowance may indicate a point at which it might be worth switching to savings formats other than a pension, such as individual savings accounts (Isas). Investment growth can push your pension pot towards the limit.

“Anyone with more than about £500,000 in a fund and a few years to go runs the risk that they are going to exceed a million and it becomes almost worthless saving into a pension beyond that amount,” says Jamie Jenkins, head of pensions strategy at Standard Life.

Special Report

Rising longevity is a cause for celebration, but how can the state afford to keep an ageing population? What efforts is the government making to ensure everyone saves for retirement — and how is the private sector responding to demand?

Many savers opt for a combination of pensions and Individual Savings Accounts (Isas), he says.

5. Near the time

As retirement approaches, savers can think more specifically about the post-work life they want and the amount of money required to live it.

About two-thirds of pre-retirement income is a good starting point, according to Standard Life. The fall in income is often made up in savings on costs associated with working life, such as commuting. Many workers have paid off their mortgages by this point, too, saving on housing costs.

Like other pension providers, Standard Life offers a calculator, where savers can input the lifestyle they want such as cars, holidays and so on and receive an estimate of the income they need.

Savers should remember to take into account the state pension, which is this year being revamped to a flat-rate system, under which retirees with 35 years of national insurance contributions will be paid at least £151.25 per week, which may be liable for tax.

For those disappointed with the income they are expected to receive, there are still options. Workers are advised to start saving in their 20s, but those who begin at 30 could add more than 40 per cent to their eventual savings by continuing to work until the age of 65 or 70, Scottish Widows says.

And many people choose to increase pension contributions steeply shortly before retirement, says Mr Parkin.

“The new pension freedoms give the ability to be a bit more positive about making contributions to pensions as they get closer to retirement,” he says.

Comments