Is social media empowering Dutch populism?

Dutch voters go to the polls on Wednesday amid mounting international concern over the role of social media and so-called “fake news” in recent political campaigns.

Geert Wilders, leader of the anti-immigration Party for Freedom (PVV), which is projected to finish as the second- or third-largest party in the lower house, makes no secret of his disdain for established news outlets. Twitter is his social network of choice: between December and February he repeatedly shared a cartoon depicting US president Donald Trump pitching a ball labelled “social media” over the heads of a group of reporters into the hands of an everyman in an armchair.

French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron last month accused Russian state-owned media outlets RT (formerly Russia Today) and Sputnik of attempting to influence the outcome of next month’s French election by “spreading fake news”. In the Netherlands, Dutch officials have demanded that votes be counted manually in order to allay concerns over potential hacking.

FT Data set out to discover what we could learn about Mr Wilders and his followers by analysing social media.

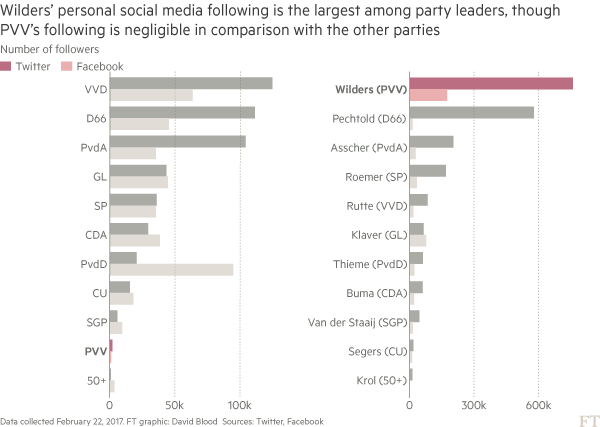

Follower numbers are a commonly recognised indicator of social media influence. Snapshot counts of Twitter and Facebook followers reveal that, in contrast to most other party leaders, Mr Wilders’ personal social media following dwarfs that of his party’s accounts by a ratio of 330:1 on Twitter and 133:1 on Facebook. By comparison, sitting prime minister Mark Rutte’s followers are outnumbered by those of his party, VVD, by 1.5:1 on Twitter and 3.4:1 on Facebook.

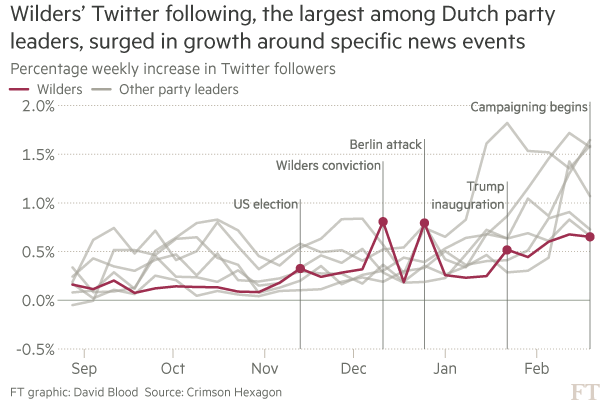

However, an examination of the rate of growth of Dutch party leaders’ Twitter followings reveals Mr Wilders’ to be growing comparatively slowly — which is to be expected given that his is the largest among party leaders’ followings. More intriguing are the bumps in the growth rate of the Wilders following, several of which coincide with specific news events. In particular, Mr Wilders’ conviction for race-related discrimination offences on December 9 last year and the terrorist attack in which a truck was driven into a Berlin crowd on December 19 boosted Mr Wilders’ following, which may suggest a reactive component to the motivations of people following Mr Wilders on Twitter.

The accusations of election interference in France made by the campaign of Mr Macron prompted a denial by RT, which said in a statement that it “adamantly rejects any and all claims that it has any part in spreading fake news in general and in relation to Mr Macron and the upcoming French election in particular.” The US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, however, asserted in a January report that RT and Sputnik functioned as part of a Russian “state-run propaganda machine” that was deployed in an attempt to influence the outcome of the US election.

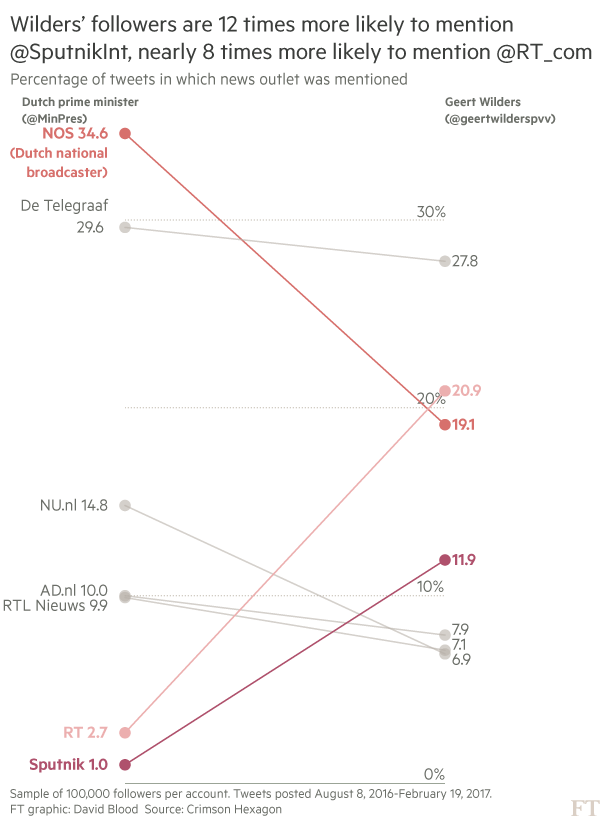

FT Data calculated the frequencies with which a random sample of 100,000 of Mr Wilders’ Twitter followers mentioned the accounts of RT and Sputnik (@RT_com and @SputnikInt), along with those of the top five Dutch news outlets over a six-month period. We compared these to a sample of the same size taken from followers of the office of the Dutch prime minister (@MinPres), a non-partisan governmental account.

Although Mr Wilders himself did not disproportionately share content from either outlet, his followers were 12 times more likely to mention Sputnik and almost eight times more likely to mention RT than followers of Mr Rutte, prime minister. Notably, Mr Wilders’ followers mentioned RT more frequently than they did the Dutch national broadcaster NOS (@NOS).

Social network bots — fully or partially automated accounts created for the purpose of strategically influencing online conversations — are a big concern for people studying the consequences of social media for democratic processes. Philip Howard, professor of internet studies at Oxford university’s Oxford Internet Institute and researcher with the OII’s computational propaganda project, has published extensively on the technology and impact of “political bots”. Prof Howard and his team revealed that political bot activity around the 2016 US election “reached an all-time high”, with pro-Trump automation activity exceeding pro-Clinton activity by as much as 5:1.

Live event: The rise of the right

Join FT Commentators in London on March 16 to discuss the rise of right-wing nationalism in Europe.

Bot identification is a complex process that involves training machine-learning algorithms to evaluate suspected bot accounts by applying a series of metrics. A key metric used by the OII project team is tweet frequency: “Our threshold is 50 posts per day,” says Prof Howard. “There are occasional false positives, but it is very rare to find a human — even a politico — tweeting 50 times per day using at least one of the major hashtags.”

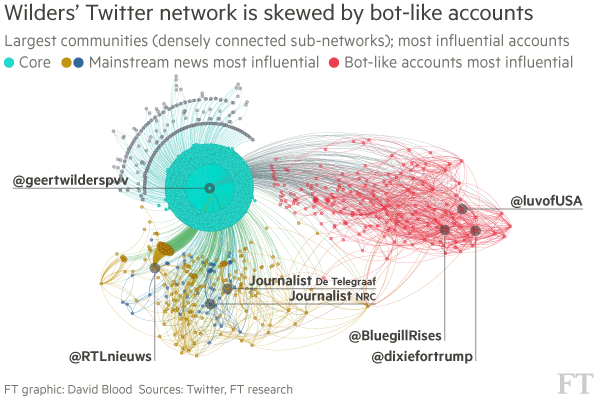

FT Data took another random sample of 10,000 of Mr Wilders’ Twitter followers and used network analysis techniques to uncover the underlying structure of this segment of his following. By identifying the followers who also followed each other, we were able to categorise users into distinct communities.

We identified four major communities: a core of users centred around Mr Wilders himself who followed few, if any, other followers; two communities in which the most influential users were mainstream news outlets or journalists; and a final, large community distinct from the mainstream news communities in which three of the five most influential users displayed bot-like characteristics.

These users — @BluegillRises, @dixiefortrump and @luvofUSA — tweeted on average 88, 156 and 123 times a day, respectively, with maximum tweet rates of between 340 and 400 tweets a day. It was unclear at the time of publication what proportion of these users’ tweets contained political hashtags.

The structure of this segment of Mr Wilders’ Twitter network suggests a clear separation between those of his followers who follow mainstream news sources and those with connections to high-volume, potentially automated accounts.

Project support and analytics tools provided by Crimson Hexagon

Comments