What triggering Article 16 would do to EU-UK relations

This article is an on-site version of our Britain after Brexit newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

If it wasn’t so potentially serious, there has been something of the playground in this week’s exchanges between the UK and the EU in the brewing row over the future of the post-Brexit trading arrangements for Northern Ireland.

The Irish deputy prime minister Leo Varadkar warned again that the EU could have “no option” but to suspend the EU-UK trade deal if the UK triggered the Article 16 safeguards clause.

There was even some talk that the EU was mulling immediate, pre-emptive tariff retaliation against the UK, although the specifics of that idea was fairly quickly shot down in Brussels and ascribed to French over-enthusiasm.

At the same time UK Brexit minister Lord David Frost, in a statement to the Lords, took the approach that is guaranteed to wind up any antsy adversary: suggesting in gently taunting tones that the European Union “stay calm” and “keep things in proportion”.

But the attempt by Frost to depict the EU defensive messaging as overwrought and disproportionate speaks to the fact that the two sides are viewing this dispute from opposite ends of a telescope.

Frost is seeking to fundamentally upend the basis of the Northern Ireland protocol which left the region in the EU single market for goods — but he wants to frame this as mere necessary tinkering for the sake of the Good Friday Agreement.

The EU has offered what it believes is the tinkering necessary to reduce Irish Sea border controls that are a core function of the deal — but wants to frame Frost’s attempts to upend the agreement as a breach of trust that destroys the foundation on which the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) is based.

Given the scale of this gap, there was little in Frost’s statement that offered substantive encouragement that progress is being made.

Frost said that the EU’s offer of some additional flexibilities on the border, while welcome, did not address what he called “the interlinked issues of the imposition of EU law and the Court of Justice, state aid, VAT, goods standards” that were raised in the July command paper.

But that speaks again to the problem: unless you buy Frost’s new narrative that the Northern Ireland protocol (which he and Boris Johnson publicly celebrated at the time) was signed under political duress, then EU law was not “imposed” on Northern Ireland.

It was mutually agreed, by both sides, in order to avoid the return of a north-south trade border.

The point that the EU is trying to convey, therefore, with its sabre-rattling is that a UK attempt to resile from that agreement via Article 16 is not some minor bureaucratic event. It risks triggering an earthquake in EU-UK relations.

Because, to the EU, the rejection of the package of flexibilities from the EU’s Brexit negotiator Maros Sefcovic would speak to a UK decision to eschew negotiation in order to tackle the practical issues raised by the protocol, and choose the path of provocation and confrontation.

EU diplomats say that, in those circumstances, the UK could not expect “business as usual”; the Sefcovic package will have fallen, negotiations will have failed and the conversation among member states will have shifted into a new “enforcement phase”.

If EU unity collectively holds on this point — and that is still to be seen — then the discussions over precisely how expansively the UK uses Article 16 may be somewhat moot.

Britain after Brexit newsletter

Keep up to date with the latest developments, post-Brexit, with original weekly insights from our public policy editor Peter Foster and senior FT writers. Sign up here.

Frost, in his statement, warns against a “disproportionate” response, alluding to the basic concept of proportionality that governs trade disagreements and requires any countermeasures, like tariffs, to be proportionate to the damage caused.

This would be the case if the EU went down that route, but the blanket termination clause in the TCA (Article 779) does not require a reason.

Article 763 of the TCA says that “the parties shall continue to uphold the shared values and principles of democracy, the rule of law . . . which underpin their domestic and international policies”. This is listed as one of the three “essential elements” of the deal in Article 771.

The next article (772) then says that a “serious and substantial” failure to uphold any of those “essential elements” can allow either side to “terminate or suspend” the agreement “in whole or in part” after 30 days’ notice.

There are, of course, other options — elegantly set out here in a flow diagram by Professor Catherine Barnard of Cambridge university — but termination or suspension is by far the cleanest.

It remains to be seen whether the EU can muster the unity to take this route, but by threatening this ‘nuclear option’ the bloc signals that it has no intention of being salami-sliced by Frost’s tactics

Frost told the Lords that there is now a “short number of weeks” to reach an agreement. The next update will come on Friday when he meets his opposite number Sefcovic in London.

The key thing to watch is whether the EU says it sees any “engagement” from the UK — something Sefcovic said last week was still missing — which might suggest that Frost is at least playing for time, even if he doesn’t believe ‘flexibilities’ will ultimately address the problem.

But big decisions lie ahead. As today’s gross domestic product figures from the Office for National Statistics showed, inflationary pressures are building in the UK, with Brexit deepening the supply-side crunch that is slowing the country’s Covid-19 recovery relative to other economies.

Suren Thiru, the head of economics at the British Chambers of Commerce warned that “surging inflation” was increasingly stifling economic output and the UK was likely facing “a sustained period of sluggish growth” with the economy returning to its pre-pandemic level next year, “behind many of our international competitors”.

In Brussels the calculation is that it would be an odd moment indeed for the UK to start a trade war with Europe that risks weakening sterling and raising the cost of UK imports from food to fuel, increasing those already-damaging inflationary pressures overnight.

Perhaps, as my colleague Robert Shrimsley bets, Johnson will ultimately retreat for that very reason; or perhaps he will roll the dice and bet the EU will not really go there; and then if it does, retreat after the fact.

Either way, once again it looks like a rocky Brexit road to Christmas.

The Financial Times is bringing together government and business leaders, public policy experts and investors to discuss the policies, strategies and investments needed to drive innovation, skills and jobs for Europe’s recovery. Sign up here to join the Future of Europe webinar on November 17.

Brexit in numbers

Many aspects of Brexit’s implementation, particularly by the Johnson government, have thrust aside the concerns of business in the name of delivering on the political mandate of the 2016 referendum. This is particularly true of the ending of free movement of people.

But this week, as the rhetoric on Northern Ireland soured on both sides, the publication of the investment barometer by the Spanish chamber of commerce was a reminder that despite these new legal realities, business now just wants to get on with it — if it is allowed to.

Spanish investment supports more than 150,000 British jobs, total trade is worth £36bn a year and — as the numbers in the barometer show — investment has been recovering since 2020 after dropping off in 2018 and 2019 because of uncertainty caused by Brexit.

Lord Gerry Grimstone, the UK’s investment minister, spoke at the event to launch the barometer and was rightly full of warm words of encouragement for Spanish investors in the UK — as was his Spanish counterpart Xiana Méndez.

The mood was positive and forward-looking, with a palpable desire not to slide back into more destabilising disputes, and yet there could be no avoiding the concerns among businesses that Brexit is far from ‘done’.

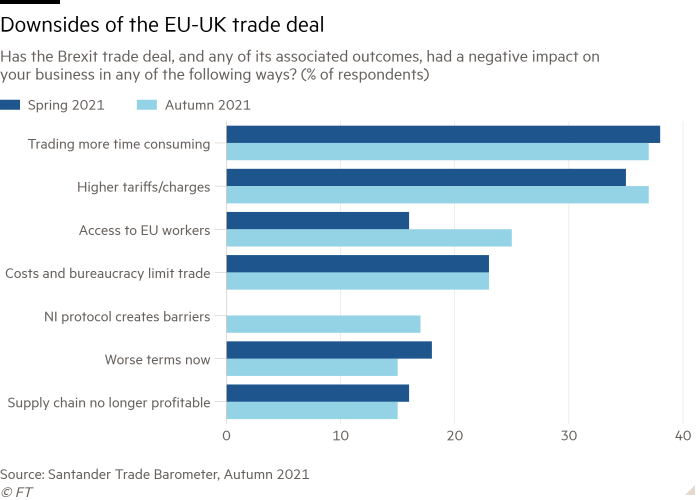

As the above chart shows, the challenges businesses are facing as a result of Brexit are not subsiding — labour shortages, bureaucratic costs and logistics are all still combining to crimp growth, profits and investment.

The event heard from a sobering panel of senior executives of four Spanish businesses — Santander Bank, Cellnex (mobile phone infrastructure), Exolum (liquid transport and storage) and Gestamp (car part maker) — who did not flinch about expressing their concerns.

It is not just a lack of UK workers that troubles them, but the cost and bureaucracy of bringing in high-skilled workers from Spain — which is the other, often under-reported side of the UK’s new immigration rules.

There was frustration but also real regret that so many decades of deep and fruitful co-operation between two close neighbours had appeared to count for nothing in the trade deal negotiated by the UK.

Senior and skilled Spanish workers now face a full-on third-country visa process which is costly, cumbersome and — according to the panellists — risks negatively influencing investment decisions over time.

What the executives wanted, first and foremost, was stability of decision making between governments, followed by greater efforts to reduce the barriers thrown up by the EU-UK trade deal.

Top of these was a desire to improve mobility provisions in the TCA; and more broadly to move on from confrontation to co-operation and try to deepen the recovery in investment already seen in 2020.

Surprise to report, no one could see the upside in an EU-UK trade war.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

Earlier this week I wrote an Article 16 explainer, on why it has become so controversial, how it could affect relations between London and Brussels more broadly and which parts of the protocol the UK want to change and why. Read it by clicking here.

In his column this week Martin Wolf writes about what he calls a “game of chicken” between the EU and the UK over the Northern Ireland protocol, which he predicts will end badly.

Not wanting to stoke EU-UK tensions further, the European Commission has agreed to give European banks and asset managers more time to access UK clearing houses for the trading of euro-denominated derivatives.

Comments