Gavin Turk: ‘We are what we throw away’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The laureate of waste – not the most exalted of titles, but I’m sure Gavin Turk won’t mind me calling him just that. Since he emerged in the early 1990s – a leading light among the group that became known as the YBAs – waste, and what it says about mankind, has been an enduring obsession in his work.

He has displayed black bin bags, apple cores, flat tyres, cardboard boxes, spent matches and discarded sleeping bags – all playful but also charged trompe l’oeils, cast in bronze and intricately painted to look like the real thing. There have been loving recreations of discarded Skips crisp packets painted on brown paper bags, mobiles made from old car wheels, wire and scaffold poles, and masticated chewing gum-shaped cufflinks in resin and 24ct gold.

His subject matter may often be the worthless detritus of everyday life, but he has made a good living out of it – a paradox that he is more than happy to acknowledge when talking to me about his latest exhibition, Letting Go, at Reflex Amsterdam. “It is a commercial exhibition in a commercial gallery. And, obviously, in a perfect world artists probably want to show in museums and places where, in theory, no one is talking about money.” He pauses. “Not that money isn’t super important…” As to what waste signifies to him – it’s pure portraiture. “We are what we throw away. If the secret services or whatever are trying to make a portrait of someone, they go through their rubbish and can learn everything about them.”

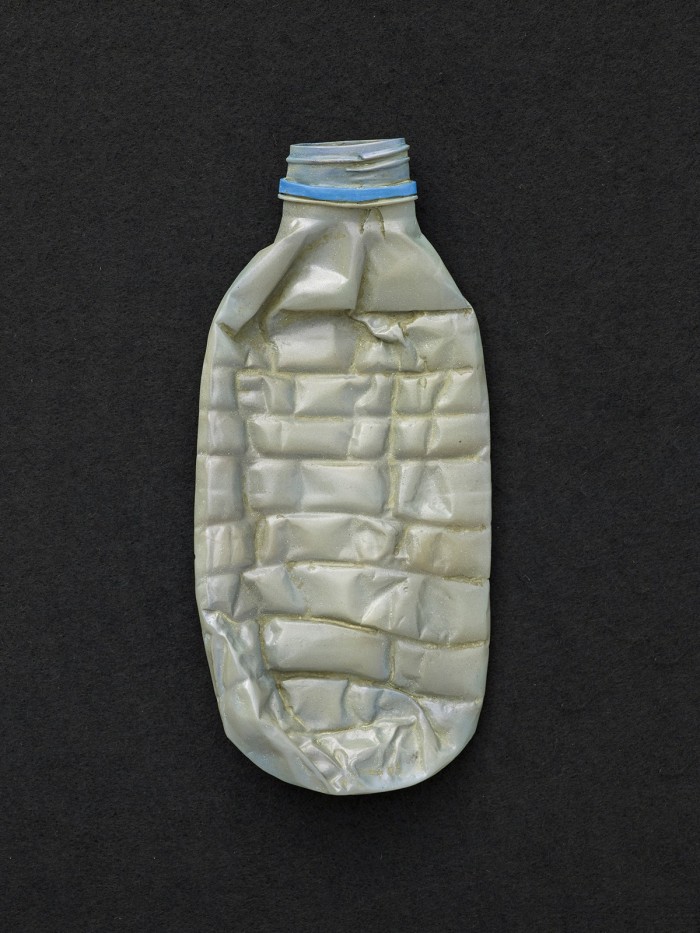

In this show he fixes his gaze on the single-use plastic water bottle, once so chic that it was carried down the catwalk by supermodels in the 1980s, now one of the most reviled, least eco-friendly objects on the planet. It’s estimated that the UK uses around 13 billion plastic bottles each year, of which just over 50 per cent are recycled. “It’s almost like now that plastic has fully taken over and become ubiquitous, we’ve realised that we don’t need it and don’t want it,” he says. “The water bottle is incredibly powerful because it contains this stuff – water – into which the plastic is now starting to leak back as microplastics, breaking the water. There is a sort of strange, slightly scary loop that we’ve found ourselves in.”

The works he has created for the exhibition have an uneasy beauty. He’s returned again to casting in bronze, making extraordinarily lifelike sculptures of bottles that he picked up from the streets, flattened and twisted by the tread of human feet or the wheels of vehicles. “Making a squashed bottle in bronze and painting it to try to look transparent is kind of a crazy idea,” he admits. “I think I quite enjoyed the impossibility of it. Why would you even dream it, that you could paint a transparent bottle?” There are also silkscreens and acrylics showing his trademark bin bag, and watercolours of squashed bottles, which – and I never imagined writing such a sentence about a representation of a crushed plastic bottle – are loaded with lyricism and pathos. Given the destructive effect such bottles are having on the environment, I wonder how Turk is able to find beauty in them. “If you look at them and start to think about them, register them, you’ll see the different kinds of transparency are very carefully controlled by the drinks manufacturers. You’ve got sort of curved lines and lots of things that seem semi-structural but are also very aesthetic. There’s the history of water, man and drinking there. There is a sort of museological feeling to these things, which I think you don’t really get when it doesn’t get re-presented to you. The re-presentation of these bottles will give people a kind of pang of the sense of the aesthetic beauty of the bottles.”

It’s not quite what I’d expected, considering the take‑me-or-leave me, punky attitude that aspects of his biography suggest. He famously epatéed the Royal College of Art in his postgraduate show by offering up a whitewashed studio with a blue heritage plaque reading “Gavin Turk worked here, 1989-91”. The College refused to present him with a degree, but, still, what chutzpah. He turned up to the private view of Charles Saatchi’s now-legendary Sensation show dressed as a homeless person, reeking of days of unwashedness and cigarette butts. One of his seminal pieces represents him as a waxwork dressed like Sid Vicious, and last year he was one of 82 protesters arrested at the demonstration by the environmental campaign group Extinction Rebellion that blocked five London bridges. I was expecting more of an agitprop firebrand.

It’s all very well pondering the museological beauty of squashed plastic water bottles and reflecting on how “taking part in making art is about the conversation, the discourse”, but should his new exhibition also be seen as a call to arms to the environmental and climate-change cause? Is it informed by the same mindset of taking direct – albeit non-violent – action that saw him arrested?

He pauses. “I guess that there is this curious thing with me and my art and my life. I think back in the 1990s I had this slight split. There was this artist called Gavin Turk and there was just me personally. I had a different signature for my artist name and I think there was a small divide between me, Gavin Turk, and an artist called Gavin Turk. I think that my involvement with Extinction Rebellion [which aims to compel governments to take action against climate change] is kind of my private Gavin Turk, and at the same time my private Gavin Turk is going to try to push and exert as much energy as he can on my artistic Gavin Turk. Since getting involved with Extinction Rebellion I’m now not flying, which is really difficult because suddenly America is a long way away and that is where the most prolific, verdant artwork is. I am now also thinking, ‘Can I stop driving my car?’ What do you do?”

Among the other things Turk is worrying about: the money being spent on the Spider-Man computer game his son is working on (it could be “spent on trying to be a little bit more problem-solving in the world”), overpopulation (“basically for every one when I was born 50 years ago there’s now two, and everybody wants to live the biggest life that they can”) and climate-change deniers (“before, there was always a sort of sense that somehow the truth or the good would come out anyway, but now . . . ”).

If this all makes him sound like a hand-wringing pessimist, nothing could be further from the truth. He’s full of twinkly, slightly madcap, macabre musings on where humankind’s salvation might lie. This on overpopulation: “I also fear that the rollout of 5G will lead to some kind of magnetic radiation scandal. Everyone is so exposed to short-wave radio frequencies that they’ll end up becoming sterile. Maybe that will help.” Cue that wild laugh. This on how to turn plastic back into oil: “I did start thinking that if stuff can come back to life through pressure, then maybe it’s just an energy problem – we can’t generate enough energy to put the plastic under enough pressure that it just returns to oil.” And there’s no question that the act of creating works of art remains an enormous joy to him despite being “surrounded by a slightly end of the world scenario”.

I finish by asking him about WH Auden’s line “poetry makes nothing happen”. Does Turk believe that’s true of art? “I don’t know if it can change anything. I think that it’s an account and record of where we’re at and what we’re doing. It can be something incredibly enjoyable and it can be a platform or a place to hold a discussion and to give some visual presence to where we are, what’s around. Think of cavemen painting in their caves. They were probably dreamers. They were probably not the ones at the front of the pack hunting the bison or whatever it is. They were just hanging out in the cave dreaming and being the ones who were writing their stories on the wall. Did it change anything because they wrote that there, because they drew those pictures? I don’t know.”

Letting Go is at Reflex Amsterdam (reflexamsterdam.com) from 19 October to 6 December 6 2019.

Comments