Danny Boyle on why art is a human right

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Earlier this year, a tropical typhoon called Dineo touched down on the coast of Mozambique, transforming the surrounding region into something like the set of a climate change thriller. Arriving in the normally drought-sick Free State, a South African farming province, I find it dotted with patches of green, while nonplussed cows slosh through the mud. In the middle of all this, a remote community called Rammulotsi is playing host to the Oscar-winning film director Danny Boyle. He stands in a neatly swept church hall, bending over tables to examine dozens and dozens of children’s drawings.

Boyle is tall and lean, and moves with the same antic energy that distinguishes his work. “Aren’t these drawings wonderful?” he asks of no one in particular. The 60-year-old Mancunian peers at colourful renderings of Rammulotsi life: a dog loping across a street; a teetering shack; kids stuffed into a minibus taxi. His visit has been organised by a UK-based creative arts charity called Dramatic Need, for which Boyle has served as a trustee since 2007. Their flagship Piet Patsa Community Arts Centre, located on a farm about 10 miles away, is in the market for some new decor and the best drawings, as picked by the world-famous director, will soon constitute a giant, wraparound mural.

“They’re building f***ing walls everywhere,” Boyle says, his nose almost touching the images. “And artists paint them.”

Boyle has been shooting movies and mounting theatre productions since the 1980s. He started out at the BBC, hit the zeitgeist on the head with the dyspeptic caper film Shallow Grave in 1994, followed it up with the generation-defining Trainspotting, and has remained devoted to genre- and medium-hopping ever since — Mumbai urchins made good in Slumdog Millionaire; the Aaron Sorkin-penned jabberfest Steve Jobs; the London Olympics opening ceremony, Isles of Wonder, a popular culture obstacle course through British history. In the coming months, he will direct a new TV series called Trust , about the 1970s kidnapping of John Paul Getty III and starring Donald Sutherland and Hilary Swank.

Since the mid-oughts, Dramatic Need has, among other things, served as something of a reset button for Boyle’s agile mind. This trip to South Africa has a specific goal: he will listen to personal monologues written by local children, and help choose a selection to be adapted by leading playwrights and performed in New York. According to their press material, the charity’s mandate is to use art and drama to help “vulnerable children regain hope and self-belief in the face of conflict, trauma and hardship”. About 5,500 kids have passed through their programmes in South Africa and Rwanda — not a huge number, but nonetheless significant given the lack of extracurricular (or even curricular) activity in many of their communities.

All of these children were subject to the aftershocks of their countries’ terrible histories, and no matter how many times people are asked to forgive and forget, trauma works its way into everyday life with remarkable persistence. In after-school and weekend classes run by the charity, the kids are encouraged by local tutors to free associate and to play — to write, to draw, to act, to sing, to thump joyfully on marimbas.

Every Rammulotsi kid has a story, many of them nightmarish, and Dramatic Need’s core belief is that by sharing these stories, healing can begin. Children in the drama programmes craft monologues from the raw material of their experiences. As a means of fundraising, the New Zealand-born, UK-based founder and CEO Amber Sainsbury, a former actor, leans on her industry connections to massage the monologues into honed pieces of dramaturgy.

Playwrights and screenwriters including Tom Stoppard, Lynn Nottage and Neil LaBute have all obliged in the past, and their interpretations have been performed on stage by actors for whom Oscar nominations are commonplace. Not just any stage, mind you: The Children’s Monologues was first produced at the Old Vic in 2010, and then again at the Royal Court in 2015. (There were simultaneous performances by the children in Rammulotsi, and by local actors in Johannesburg.) This year’s event, scheduled for November, will raise funds both for Dramatic Need and for the production’s New York venue, Carnegie Hall. Charlize Theron, Trevor Noah, Susan Sarandon, Daniel Kaluuya and Ewan McGregor, to name a few, are currently attached to star.

Boyle’s job is to serve as the in-house directorial talent. “Amber got in touch wanting to get this up,” he says. “I liked her, it sounded interesting and I wanted to support her. But it is a chain of belief with stuff like this. It’s like the film work — it starts with an idea, and then you have to start evangelising, bringing others on. Because it’s so easy to be cynical.”

***

Certainly cynicism has become a default cultural setting, one that Boyle has most recently explored in his Trainspotting sequel. But he also directed the kid-friendly Millions and the chop-off-an-arm-to-live 127 Hours, to say nothing of the Olympic Games opening ceremony, all of which are odes to the enduring loftiness of the human spirit. His involvement in Dramatic Need squares with this impulse, and South Africa happened to function as something of a catalyst for how he sees these things. “I grew up in the time of the great anti-apartheid protests,” he tells me. “Back when it dominated the news. It was basically the only thing on TV.” The country’s recent narrative arc — from Nelson Mandela walking free from prison to the grim rot of Jacob Zuma’s current presidency — hasn’t soured Boyle on Dramatic Need, or on the complex outcomes of development aid in general. Rather, the reverse is true.

“You know, I sort of cut my political teeth in Northern Ireland in the mid-1980s, when I was dispatched by the BBC to produce television dramas,” he says. Like most people at the time, he was drawn immediately to the Troubles. “Back in those days, I had everything figured out from a Marxist dialectical point of view — it was just a class issue, right?” He guffaws. “Um, that thinking didn’t last long. It was one of the very very big turning points in my life, because I just couldn’t see how people could change the situation.” As a means of expressing his despair, he produced Alan Clarke’s Elephant (1989) — a virtually wordless catalogue of 18 local murders that contained no backstories, no music and no ostensible hope.

But while Elephant at first seems almost nightmarishly nihilistic, the film is in fact hopeful — implicit in its structure is a plea for the killing to stop. “And a few years later, people got together and sorted it out,” says Boyle. “I mean, not entirely successfully, but it was a huge improvement.”

Indeed, by the time the press had crowned Boyle as British film’s new enfant terrible, many of the 20th-century’s bogeymen had made a run for it: the Soviet Union, the Khmer Rouge, apartheid. But now, according to Boyle, the old walls are being erected again. “It seems obvious that culture, art, is a human right,” he says. “I know it sounds pretentious, but we’re storytellers. And there’s something wonderful about that, when everyone is building barriers.”

It is essentially humanising, he contends, to link the experiences of a child in Rammulotsi with, say, Benedict Cumberbatch (who took part in Dramatic Need performances in 2010 and 2015) on a London stage. And for Boyle, the fact that this is undertaken by aid-dispatching “bleeding hearts” isn’t a drawback, but the entire point. “There’s something about the guilt trip of aid that keeps a channel open in you,” he observes. “The danger of success, be it personal or be it with your country’s economy, is that it leaves you insulated. Clearly there are huge reservoirs of problems here in Rammulotsi — huge amounts of violence and sexual violence. The arts allow you not to understand them necessarily, but to channel them. You can look at them. You can see them. Rather than have them just swallow you.”

Boyle sniffs from a combination of jet lag and flu. “I truly believe art is transformative,” he says. “I really do believe that.”

***

On his first day in the township, Boyle stands with Sainsbury and several others at the back of the church hall as the children stream in. The programme is a busy one — local kids will produce a series of theatrical and musical performances, and then read their monologues. This time, the best stories will be repurposed by a number of South African playwrights, and then make the journey to New York City.

I sit alongside a sweet-faced 14-year-old named Nthabeleng Radebe, a Dramatic Need student for the past three years. She wears a school uniform of sharp green and yellow, and tells me that she’d initially been reluctant to sign up. Her friends had encouraged her to do so. “No one judged you,” she says of the programme. “You are you. Some people are harsh to others about their backstories. But not here.”

Radebe’s story wouldn’t be out of place anywhere. Her father abandoned the family when she was a toddler, and she’s had only intermittent contact since. But the pain and heartbreak she channels in telling it, the unvarnished sadness, make an old story fresh again.

The plays that follow, each about 10 minutes long, depict incidents that no child should ever witness. The first concerns a fight outside a tavern so violent that Boyle gasps audibly. The second is about a teenager who goes off to a party, and returns home with morning sickness. Cut to her schoolmates mocking her distended belly in class.

Many of the monologues are weaponised tales of hell on earth. In 2015, a teenager named Goodness Ramahlade related a story of being sexually abused by an uncle, later read on stage in London by Game of Thrones star Kit Harington. Now, she asks why her relationship with another woman deserves such hostility. “Why is my love considered a sin?” This is followed by a brutal tale of child sexual abuse and gang rape — a story that could, frankly, send a Carnegie Hall audience screaming into the Midtown drizzle. Suicide, gangsterism, loan sharking, stabbing, shooting, rape — we spend the afternoon in the middle of it all, the children coughing up for each other the violence of their circumstances. It is all insanely moving, when it isn’t profoundly disturbing.

“What I liked about it,” Boyle later tells me, “is that it was theirs. It wasn’t white people dictating to them. It didn’t feel at a tangent to them. Sometimes I think I should just give it all to Médecins Sans Frontières. Poof! The whole lot of money,” he says. “And then you see something like this.”

***

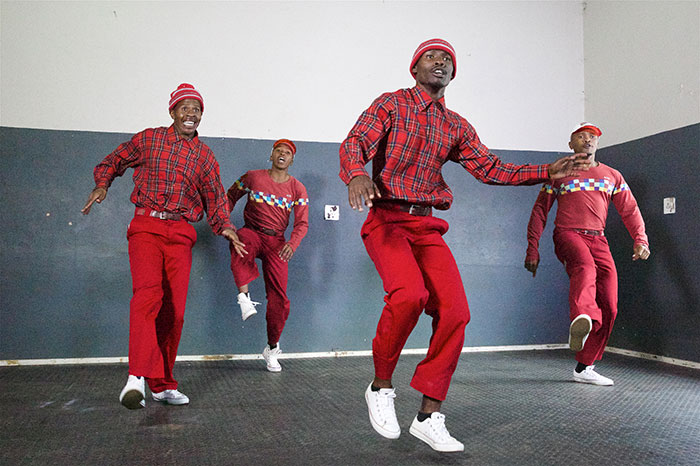

Head south-east out of Johannesburg towards the sprawling township of Vosloorus, cut north into a neighbouring township, and you will find the Katlehong Arts Centre. Several days after the Rammulotsi performances, Dramatic Need, with assorted hangers-on, arrives in convoy, dodging traffic and rain squalls. They have come to find an opening act for the Carnegie Hall performance, a quest that will take the form of a talent show. It has been decided that a distinctly South African art form is required to link the country to the monologues, and the best out of eight pantsula dance crews will be sent to New York.

Part break-dance, part mime, part duck-like waddle, pantsula is a dance that rose out of the townships during apartheid. The practice has since become professionalised, and crews of four now compete across the country. This particular contest has been organised by the Impilo Mapantsula association’s Sicelo Malume Ka Xaba, a veteran pantsula dancer who introduces Boyle as “the biggest director in the world”. At which Boyle, to his credit, shakes his head and hands in a reasonable approximation of a pantsula move.

Xaba and his team have set up a judges’ panel and a sound system, and in a low-rent version of South Africa’s Got Talent, we watch the crews battle it out: the at times joyous, at times achingly sad experience of township life expressed through four bodies moving in unison, but not perfect unison.

“It’s so good,” says Boyle. “It’s just beautiful.”

The past several days have been a gruelling tour of South African misery, interspersed with moments of superb artistic expression. If Boyle had any misgivings about what a British charity was doing exporting local children’s monologues to New York City, they have long dissipated.

“How can you turn your back on people in order to make the point about what governments need to do in the long term?” he asked me, earlier. “It’s very difficult, isn’t it? There are extraordinary people doing this kind of work, and those things are driven by empathy. And if you eradicate empathy, you get very soon to a Soviet-style command economy — where it’s like, there’ll be casualties along the way, but you’ll have this monolithic system in place.”

For Boyle, institutions like Dramatic Need don’t replace the state, so much as help nudge the formation of a functional society forwards. And he doesn’t have to look far from home for historical confirmation. “The philanthropists who preceded the establishment of the welfare state — and here, I can only speak about the system in Britain, because it’s the one I know most intimately — the Victorian philanthropists, those that built the Peabody estates: they were trying to create some kind of safety net to actually look after people in this mad scramble that was the industrial revolution. They were the vanguard of it, and you wouldn’t criticise them — they feel like a very natural, pre-political example of empathy working alongside an emerging society.”

After the pantsula crews have run through their routines, I encounter Boyle in the men’s toilets. The surroundings don’t seem to bother him — he wants to relate to me an experience from the previous day, when a star named Chi Mhende from South Africa’s long-runnning TV soap Generations had come to address a group of kids from Dramatic Need’s programme. Mhende, a woman, is famous for playing a male character, and her fluidity has become something of a South African cultural touchstone.

“She was amazing with them,” says Boyle, his eyes welling up with tears. “She asked the kids to find something good to say about themselves. It’s a tough question for anyone, but the boys . . . ” he trails off. “Then she said, with incredible empathy, ‘Black man, you have it the worst, because everyone is after you.’”

For Boyle, the pantsula dancing is a last confirmation that art offers freedom, not only from the tyranny of others, but also from the tyranny of the self. “The number of things that connect people, and treat people as equal, are very very rare,” he had told me earlier. We walk back into the last of Dineo’s rainstorms, the cyclone all but having worn itself out.

Richard Poplak is a South African journalist

‘The Children’s Monologues’, directed by Danny Boyle, is at New York’s Carnegie Hall on November 13. To find out more, go to dramaticneed.org

Photographs: Lisa King

Comments