A guide to the Fed’s rate rise dilemma

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When in July Janet Yellen last spoke publicly, she sounded like a Federal Reserve chair who was ready to take action. America was on course for higher interest rates this year, in a move that would underscore the country’s recovery from the trauma of the great recession, she told Congress.

Since then international factors have intervened to make the outcome of Thursday’s meeting far more clouded. Futures prices suggest odds of just 25 per cent on a quarter-point rate increase, as investors argue that last month’s violent moves in financial markets, a sharply higher dollar, weak inflation and wage numbers and worries about a Chinese slowdown will convince the FOMC to do nothing.

So what could convince the Fed to raise rates?

The case hangs heavily on the domestic US economy, which is outshining its overseas partners. The Fed has set itself twin tests of seeing continued improvement in the jobs market and having confidence in inflation returning to target before it starts to lift rates.

The jobs side of the equation is unequivocally strong. The labour market is at full employment, judged by the Fed’s own estimates, with unemployment closing in on 5 per cent — the bottom end of the Fed’s estimate for the long-term jobless rate of 5-5.2 per cent.

The Fed thinks unemployment is the best single indicator of labour market slack — and slack is fast disappearing. Wages and inflation may not be that far away from picking up, according to the Fed’s economic models, and that means interest rates need to start rising.

While inflation and wages have remained low, Ms Yellen has said she does not need to see them accelerate in order to be confident that inflation is heading back to 2 per cent.

Why do traders think the Fed will stay on hold?

Given multiple uncertainties, both domestic and foreign, the “wait and see” option is undoubtedly attractive to some Fed officials.

Recent market developments including the fall in equity prices, rise in the dollar and widening of credit spreads have led to a tightening of financial conditions that could drag on US growth and the country’s doggedly sluggish inflation.

Tighter financial conditions were enough to stop the Fed from tapering its bond purchases back in September 2013. They could be enough to swing the debate.

The most powerful central bank in the world is considering whether to raise its record low interest rates for the first time in nearly a decade. Even before the US Federal Reserve makes a move, the effects are reverberating throughout the global economy. Our project explores how.

What is more, Beijing’s mismanagement of its exchange rate policy and stock market interventions have fanned worries that China is facing a serious economic slowdown.

This has already led to lower commodity prices, which could weigh further on US inflation, as — crucially — could the dollar’s strength. On top of this, Ms Yellen has suggested in the past that she would take notice if market-implied inflation expectations sank — something that has happened in recent weeks.

As an ancillary issue, the US government could soon be heading for a shutdown as Republicans threaten to block public funding. Shutdown worries weighed on FOMC deliberations in September 2013, although in the event the US economy did not suffer badly.

What messages are likely to come from the FOMC?

After weeks of muddy signalling, investors will welcome some clarity about the committee’s intentions.

The two most likely outcomes are: (1) that the Fed leaves rates on hold while keeping a rate rise on the table in 2015; or (2) that it raises rates but emphasises how gradual subsequent tightening will be.

In the first scenario — a “hawkish hold” in market lexicon — the FOMC would keep rates at near-zero but signal that a possible move in October or (more likely) December remains on the cards.

The second scenario — a “dovish hike” — involves lifting rates by a quarter-point but suggesting that no more moves will come in 2015, and that subsequent increases will be very gradual.

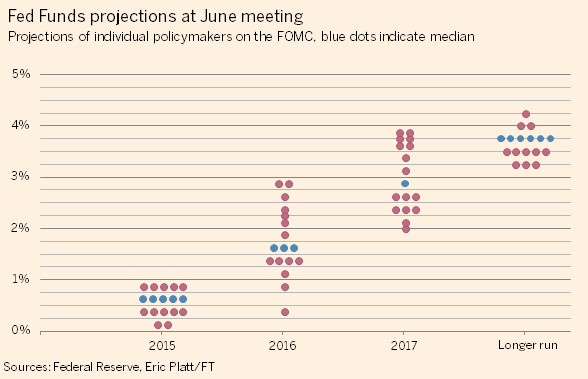

This could be signalled via the so-called “dot plot” showing Fed policymakers’ interest rate expectations, coupled with soothing language from the Fed chair at Thursday’s press conference.

Growth figures for 2015 may be bumped up a little following a run of strong data, while the run-up in the dollar since June may hit GDP growth in 2016, pulling Fed policymakers’ median estimates down to 2.4 per cent growth, according to JPMorgan Chase.

Unemployment figures should be stronger across the Fed’s forecast horizon, given the rapid pace of job market gains, while core inflation may be a tad softer next year because of the dollar.

The critical forecasts to watch are Fed policymakers’ interest rate projections. In their June forecasts, only two officials expected to wait until 2016 before raising rates.

If the Fed stays on hold and that number swells to four or more it would send a dovish signal, as would sharp reductions in interest rate predictions further down the line. Policymakers’ expectation for the longer-run interest rate is widely expected to be shaved back a little, from 3.75 per cent to 3.5 per cent.

How would markets react to a move?

Fed officials have done relatively little in recent weeks to prepare the markets for a September hike. This is partly because the central bank wants to avoid explicitly pre-committing itself on rate policy (although that has not stopped Ms Yellen from suggesting there will be a rate rise in 2015).

However, the Fed also does not like to shock markets with an unexpected rise. Larry Summers, the former Treasury secretary, pointed out this week that the last time the Fed lifted rates when market odds were as low as they are today was 1994, when there was a nasty rout in the bond markets.

That said, the Fed does not want to be dictated to by markets. And what matters more than the quarter-point move is the subsequent trajectory of interest rates.

If the Fed hikes but indicates that the subsequent path of tightening will be very shallow, this should ease nerves. And there may be some relief among some investors that the uncertainty surrounding the timing of the Fed’s first rate rise has finally been dispelled.

Comments