Africa: can João Lourenço cure Angola of its crony capitalism?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Not far from the flashy skyscrapers of downtown Luanda, the capital of one of Africa’s supposedly richest countries, is a public morgue. Celestino Chivava, who worked in the Angolan oil industry until he lost his job after the price collapse of 2014, describes how families wash the bodies of their loved ones on a slab outside.

“They put perfume in the mouth to stop the corpse smelling,” he says of the capital’s do-it-yourself funeral services. “Sometimes, when the electricity goes off, the bodies get stuck together and the families have to pull them apart.”

Oil-rich Angola is the third-biggest economy in sub-Saharan Africa, but it is also one of the most unequal, with a gulf separating a rich, politically connected elite from the mass of the 30m population. After the devastating civil war, which ended in 2002, its oil-fuelled economy, boosted by huge investment in infrastructure from China, became one of the fastest-growing in the world, piling on near-double digit growth over the course of more than a decade.

But the southern African country also became one of the continent’s most corrupt, a crony capitalist state in which proximity to the ruling People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, led for 38 years by President José Eduardo dos Santos, was the single biggest factor in personal enrichment. In a 2011 audit, the IMF identified a $32bn discrepancy linked largely to “quasi-fiscal operations” by state oil company Sonangol that did not appear in official budget accounts.

While a wealthy elite prospered, living a glamorous lifestyle on Luanda’s Riviera-style Atlantic coast or snapping up property and assets in Portugal, the former colonial power, the majority of Angolans live on less than $2 a day. Social indicators, from life expectancy to child mortality, are significantly worse than they should be for a country of Angola’s supposed wealth.

Now there is a hint of change. Angola has a new president, handpicked to succeed Mr dos Santos, who relinquished the party chairmanship last year after giving up the presidency in 2017. Many had expected João Lourenço, a former defence minister and MPLA stalwart, to continue as usual, protecting his benefactor, preserving the supremacy of the party and maintaining Angola’s tight links with China.

To their surprise, Mr Lourenço, universally known as “JLO”, has set about dismantling at least part of his predecessor’s legacy. The president has spoken of the need to help the poor in what analysts see as an attempt to shore up the MPLA’s legitimacy against an opposition Unita party that has steadily improved its electoral performance.

More concretely, Mr Lourenço has waged a public war on corruption that has ensnared some of the former president’s children, including one of his sons, José Filomeno dos Santos, who had been put in control of the country’s $5bn sovereign wealth fund towards the end of his father’s tenure. José Filomeno was detained last year for alleged embezzlement, but released this March, without charge, after authorities said they had recovered control over several billion dollars belonging to the fund.

While some see Mr Lourenço’s actions as a Xi Jinping-style anti-corruption drive designed to consolidate power — or even a vendetta against his former patron — others have glimpsed a chance for Angola to correct its course.

“So far, it’s more of a vendetta and less of a systemic clean-up, though I’m not closing the file on future progress,” says Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, an Angola expert at Oxford university.

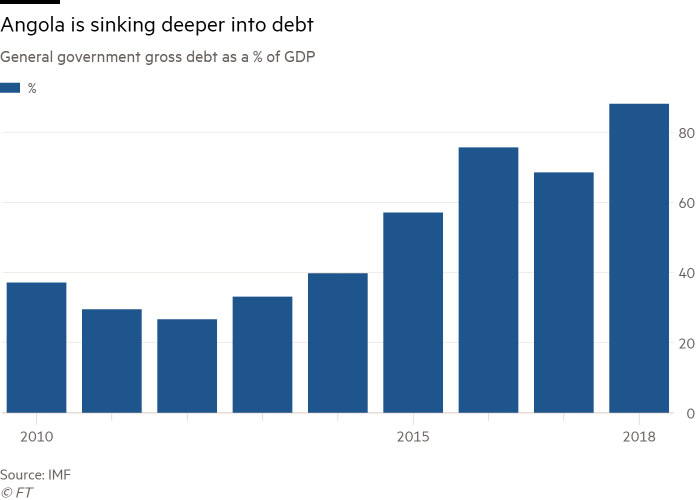

Mr Lourenço has already signed a $3.7bn credit facility with the IMF, the biggest ever such arrangement made by an African country and one that will open up one of the continent’s most opaque regimes to wider scrutiny. As part of the agreement, it has promised to cease the oil-for-infrastructure contracts with China that paid for a massive postwar reconstruction boom, but left the country heavily indebted . Angola’s ratio of debt to gross domestic product is close to 100 per cent, a serious restraint on its room for budgetary manoeuvre.

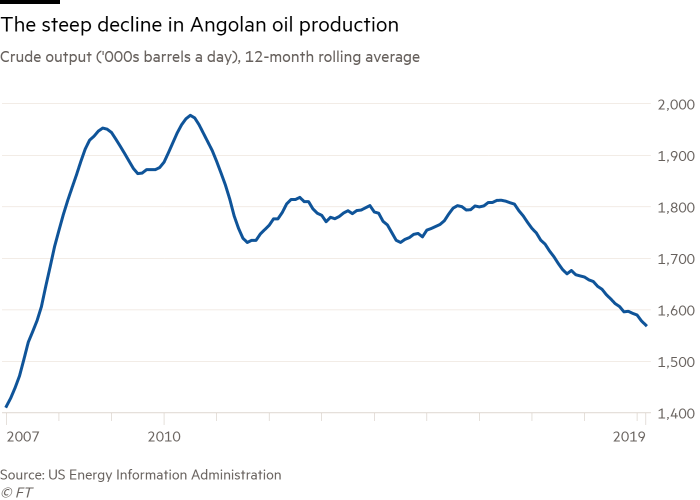

The new president has also made sweeping changes to the oil industry in an effort to revive production that has fallen from a peak of 1.9m barrels a day a decade ago to 1.4m b/d. The idea is to use tax breaks and other incentives to persuade oil majors such as Total of France and Eni of Italy to pump more from existing wells and to entice others to explore for new reserves.

As part of that reorganisation, Mr Lourenço sacked Isabel dos Santos, the richest woman in Africa and the most successful of the former president’s offspring, as head of Sonangol. The state-owned company has now been split into two, clipping its previous status as both industry regulator and operator.

Oil accounts for 95 per cent of the country’s foreign revenue, making Angola possibly the most commodity-dependent country in Africa. But lower prices and falling production have squeezed the state’s coffers and plunged the economy into a four-year recession.

In spite of its plentiful water and abundant arable land, Angola imports almost everything from tinned carrots to lettuce flown in from Lisbon. Many farmers abandoned land during the civil war and the oil economy pushed the kwanza, the currency, to unrealistic levels, making it uneconomic for businesses or farmers to produce even the most rudimentary items. Until a massive devaluation of the kwanza of 85 per cent last year, the elite simply imported everything they needed, from diesel to champagne.

Mr Lourenço is not the first to press for economic diversification. But with dwindling oil reserves, high indebtedness and a political imperative to enact social change, advisers say he has little option but to restructure the economy and make it more attractive for foreign investors.

To add to the impression of change, the president has cultivated a more modest and open public image. Unlike his predecessor, Mr Lourenço has insisted that his face does not appear on banknotes.

“This is a historic moment for the country,” says Ricardo Viegas d’Abreu, transport minister and a former economic adviser to Mr Lourenço. “We have reached a stage where we can’t continue having public expenditure as the main driver of growth.”

Mr Viegas grasps the magnitude of the task, particularly given what he alleges was the massive scale of corruption in the last years of the dos Santos administration. He adds : “Every stone you turn, you don’t find a pearl, you find a snake.”

Yet the president, insists Mr Viegas, knows that a new economy can be built only on what he calls “a legal framework [of], reasonable [minimal] levels of corruption for a developing country and rights, like freedom of speech”. Those, he says, “are the building blocks, but they are not that easy to put on the ground. Lourenço has shown the courage to move us in that direction.”

At the central bank, an opulent colonial-style structure with Portuguese murals decorating its domed entrance, José de Lima Massano, the governor, echoes the positive narrative. “The country is on the move. Things are really changing and changing fast,” he says, pointing to evidence from a drive to weed out undercapitalised banks to a new investment law allowing foreigners to enter Angola without a local partner.

The central bank has long been associated with weak supervision — including lax oversight of anti-money laundering regulations — and poor control of financial institutions, which have often been treated as personal piggy banks by those with political connections.

Mr Massano has shut several banks and instituted an auction process designed to clean up a less-than-transparent system for allocating scarce dollars. He has also stepped up the rhetoric against money laundering.

Only by cleaning up their image, he says of local banks, will they be able to repair relations with US counterparts, which have severed so-called correspondent-banking relations with Angola, worsening the dollar crisis.

“The fight against corruption by Joao Lourenço is very good news,” says Mr Massano. “One of the risks to those correspondent banks is that illicit money might go through their accounts, so no one dares do anything.”

The central bank moved to address the underlying shortage of dollars itself, a bane of investors trying to do business in Angola, by allowing the market to determine a more realistic exchange rate. “The currency was fixed to the US dollar,” he says. “It was not sustainable and we had to do something.”

Rafael Marques de Morais, an investigative journalist and notable thorn in the side of the ruling elite, acknowledges real change under the new presidency. For one thing, he says, the surveillance equipment outside his home has gone.

Although the Lourenço administration has moved swiftly against parts of the old regime, he says, others tainted by corruption have remained close to power. An amnesty on laundered money deposited abroad resulted in no meaningful return of illicit funds, he adds.

Defenders of Mr Lourenço say that, given the small size of the Angolan elite, the president has little option but to recycle educated technocrats. He has drawn a line under past misdeeds, goes the explanation, but will not tolerate new ones.

Mr Marques has a simpler interpretation. “If you surround yourself with sharks it’s because you like sharks,” he says. “If I had to summarise what’s happening in the country I would say the president came in with very good intentions, unprecedented political goodwill — and a total lack of vision on how to proceed.”

One incident that has raised eyebrows involves Manuel Vicente, a former vice-president accused of corruption and money laundering by Portuguese prosecutors. Mr Lourenço pressed hard for a trial in Angola, rather than Portugal, accusing Lisbon of interfering in its sovereignty. Since Mr Vicente’s release by Portuguese authorities last May, no trial has taken place.

A recent auction for a fourth telecoms licence — including mobile, fixed-line and pay-TV services — has also raised questions over the extent of the reform. It attracted the interest of foreign companies hitherto excluded from a market that has been dominated by Unitel, a private company until recently chaired by Ms dos Santos, who owns 25 per cent, with a further 25 per cent held by Sonangol.

The licence was won by Telstar, a company with a limited record but controlled by a recently promoted general. The arrangement, which some considered had all the hallmarks of a cosy deal from the past, was annulled in April by Mr Lourenço “to ensure a clean and transparent procedure”.

Another example of alleged business as usual has been raised by Africa Growth Corporation, a US company which provides affordable housing. AGC claims that property it developed was illegally expropriated in 2017 by a well-connected general. Although a court ruled in its favour in November of that year, says Scott Mortman, AGC’s executive chair, the Angolan police never enforced the order, obliging his company to seek compensation. Mr Mortman says the government this year finally agreed to pay $47.5m, but has since reneged on the deal, something denied by Angolan authorities.

Mr Mortman says that US companies should not do business with Angola until the issue is resolved.

Angolan officials, asked whether the incident taints the country’s claim to be a reformed investment destination, told the Financial Times the case was a private matter that no longer involved the state. “The courts have retrieved the property,” says Mr Massano at the central bank . “If they [AGC] want to sell it they have to sit down with someone who wants to buy.”

While Angola’s pitch as a safe haven for foreign investment is still a work-in-progress, the economy continues to suffer. GDP is predicted by the IMF to grow by less than 0.5 per cent this year.

A well-placed member of the elite, who spoke on condition of anonymity, says of the president’s reforms: “We are not feeling it yet. People have no food, no money, no jobs.”

Mr Marques says the problems run deeper than failing to rekindle a stalled economy and that Mr Lourenço needs to choose between preserving an MPLA that is perceived as corrupt to its core or dismantling its structures in pursuit of more fundamental reform. “The ruling [MPLA] was essentially the hotbed of those who plundered the country and those people have not been removed,” he says. The president, he adds, has “made a fundamental error” in not taking on the MPLA more aggressively.

“He cannot be a reformist,” says Mr Marques, “by saving the party and throwing breadcrumbs and false promises to the people.”

Comments