Environmentalists split on how to push clean energy’s next phase

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Environmentalists have won the battle of a generation: after years of campaigning, they have largely persuaded the world that man-made climate change is real and that fossil fuels are to blame.

Remaining sceptics — chief among them US president Donald Trump — are outnumbered even in their own countries. Instead, most governments, energy companies, investors and others are beginning the pivot towards supporting low-carbon energy sources.

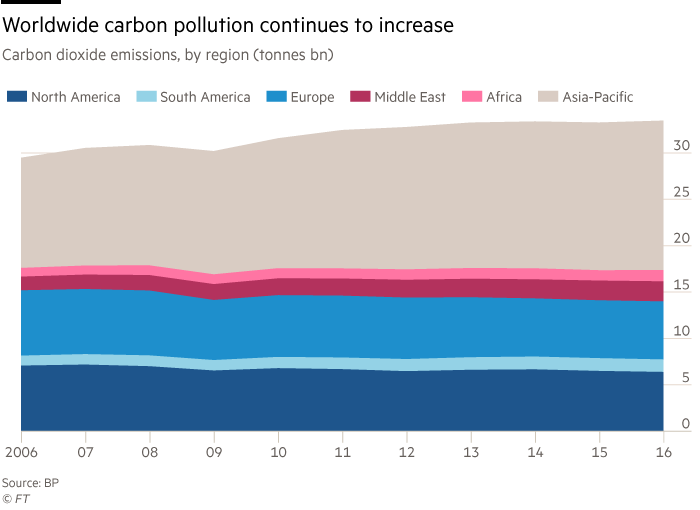

That poses a fresh challenge for environmentalists: though transition is under way, scientists say only more action than is planned will avoid the catastrophic effects of unabated global warming. Campaigners are divided on the tactics to achieve this.

At one end are grassroots groups such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, which are well known for protests that aim to obstruct polluters and mobilise public opinion.

They have no plans to abandon such tactics, even as one-time foes including oil majors slowly begin to address their contribution to climate change. This month, Greenpeace protesters dangled from a Canadian bridge for 38 hours to block an oil sands tanker.

“Those bold statements are needed more than ever,” says Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International, “because we’re in a climate crisis and it’s very clear that the pace of change is not adequate enough.”

There is also a new breed of campaigners who prefer to exert pressure inside boardrooms. These groups, including activist shareholders, investors and analysts, say there is a pragmatic case against continued investment in coal, oil and gas.

Among them is Carbon Tracker Initiative, an early pioneer in arguing the risks and rewards for investors. Founded nine years ago by sustainable investment analyst Mark Campanale with philanthropic funding, the think-tank spent several years telling investors that many of their fossil fuel assets would become “unburnable” in a low-carbon economy.

At first it was largely ignored. Then Bank of England Governor Mark Carney echoed Carbon Tracker’s warnings in a speech in 2015, and concerns about stranded assets entered the mainstream. Mr Carney’s call added momentum to a debate on where investment in future energy supplies should fall.

Fossil fuel companies now risk wasting nearly $1.6tn on oil, gas and coal projects if international efforts intensify to limit global temperature rises, according to a March estimate by Carbon Tracker.

Such numbers help the think-tank and others argue that “not only do these projects not make climate sense, but they don’t make financial sense either”, says Anthony Hobley, Carbon Tracker’s chief executive.

Such economic arguments fit well with the grassroots pressure from other campaign groups, he says. “If you have the two sides acting as a pincer movement, then the companies have nowhere to go. The two now really need to be working in conjunction.”

This joined-up campaign strategy is having some political and business effect: France and the UK are among governments urging financial institutions and companies to disclose the risks of climate change to their businesses.

European and US oil and gas groups including Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Total, ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil have responded to pressure by saying they will report on the potential impact of their activities on climate change. Shell also set a goal to halve the carbon emitted from the products it sells, while BP aims to keep them steady until 2025.

At the same time, a separate divestment campaign driven by grassroots groups has gained strong public traction. Norway decided to divest from coal in 2015 and is considering extending the policy to oil and gas even though its large sovereign wealth fund is based on exports of the fuels.

Ireland is expected to finalise a bill this year that would make it the first country to sell all its publicly controlled fossil fuel investments. The commitment comes months after the country’s Climate Change Advisory Council warned that Ireland was on track to miss its EU 2020 commitments to reduce carbon emissions.

Hundreds of cities, churches, universities, pension funds and others have also committed to some form of divestment.

350.org, one leading divestment campaign group, says the strategy is successful because it takes money directly out of fossil fuel production. The investors that have pledged some form of sell-off hold a combined $6.16tn of assets, says 350.org. Still, it is hard to calculate the value of their planned divestments and timelines for the sales are often vague.

Critics argue that while divestment campaigns generate publicity around the threats of climate change, their long-term effects are limited. Selling off shares in coal, oil and gas companies may merely shift them to investors that are unconstrained by divestment mandates and less concerned about environmental effects.

In addition, while divestment campaigns may limit the activities of western companies, they are unlikely to curtail the production and future investment plans of large state-owned oil, gas and coal producers that dominate world output.

Instead, governments, investors and businesses need to push money directly into clean energy to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, says Robert Pollin, co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. They can do this by setting policies such as commitments to use 100 per cent renewable energy by a certain date.

Such pressure could also be more effective than lobbying oil and gas producers to change gradually, Mr Pollin adds.

“Fossil fuel companies are going to have to basically be eliminated over time,” he says. “We need to be directly focused on making these markets contract — not the stock markets, but the goods markets.”

Explore the rest of our stories on Citizens and Consumers

- Indonesia sticks with coal to meet energy demand

- Mexico City seeks fix for transport pollution

- Pakistan pivots to coal to close energy gap

- China pollution obsession spawns global industry

- Carbon pricing taxes US politicians and theorists

- FT readers say carbon pricing key to energy debate

- Energy, emissions and personal responsibility

Comments