A potential solution to one of the most difficult issues in Brexit is hardly a dead cert

Simply sign up to the Trade disputes myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

FT premium subscribers can click here to receive Trade Secrets by email.

Hello from Brussels. Some intriguing goings-on in the drama of Big Phil Goes To Geneva, Or Does He? EU trade commissioner Phil Hogan has signalled an ambition to be the WTO director-general, but his exploratory manoeuvres weren’t exactly conducted with military precision. First the US, and then the EU’s member states, have declined to guarantee him the support that he wanted at this stage. He has the nomination from his home government in Ireland and was planning formally to announce yesterday, but is now giving it some more thought.

Here’s the problem. The DG race might stretch past the September target date to much later in the year. In that case, EU commission president Ursula von der Leyen would very likely appoint a replacement trade commissioner. You can’t have such a senior post in effect vacant while its holder is out campaigning for another position, not with more potential tariff aggro from the US to deal with. So does Hogan want to give up one of the EU’s plum jobs for the uncertainty of a WTO DG race he might not win? If it were us, we’d stick rather than twist, but to be honest no one comes to us for job advice, or not for a second time. Anyway, Brussels’ own Hamlet on the Hudson (Hamlet-sur-Senne, we guess) will probably make his mind up by the end of the week, so keep an eye out.

In the meantime, one person who definitely wants to be DG is the Korean trade minister, Yoo Myung-hee, who was nominated yesterday. She’s apparently well-liked on the circuit and particularly in Washington. But given the close security links between the US and South Korea, any Korean candidate will have to overcome suspicion in Beijing that they are basically an American patsy.

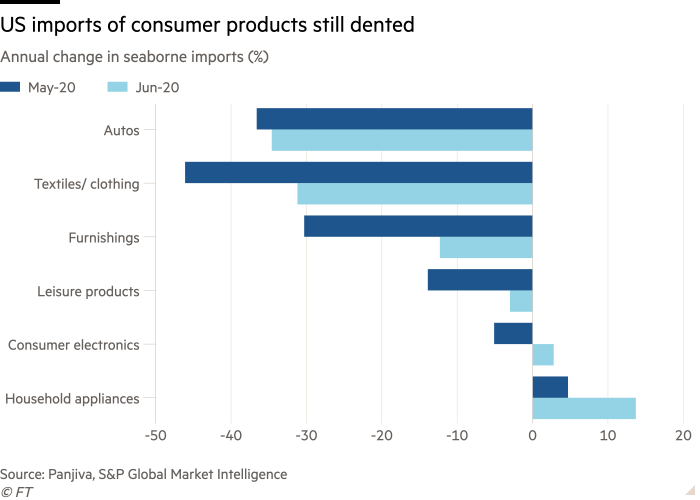

Anyway, today’s main piece is on how a tricky issue in Brexit is part of a wider problem with expecting arbitration to fix trade disputes. Tall Tales of Trade is a “told-you-so” on the UK finding preferential trade agreement negotiations harder than they look. Our chart of the day looks at the ongoing slump in most consumer product imports in the US.

Don’t forget to click here if you’d like to receive Trade Secrets every Monday to Thursday. And we want to hear from you. Send any thoughts to trade.secrets@ft.com or email me at alan.beattie@ft.com.

A scrappy grudge match looks for a level playing field

Brexit talks, currently enjoying an unusually constructive ambience but no actual progress, start again this week, and with them an attempt to solve one of the trickier sticking points. It goes like this: the EU wants the UK to sign up to “level playing field” (LPF) provisions designed to stop its companies undercutting their EU competitors with weaker rules on the environment, labour rights and state aid.

It’s the last of these that’s causing the biggest problem, especially since Covid-19 has massively increased governments’ willingness to intervene in their economies. If you take all this reshoring and industrial policy stuff seriously, that’s not just a short-term phenomenon.

The UK points out (correctly) it’s been a relatively parsimonious user of state aid in the past, and can we dial down the Gosplan-upon-Thames paranoia please? The EU counters (less obviously correctly) there’s no guarantee that will continue in the future. To be fair, it’s certainly true that both the current Tory government and the Labour opposition, even minus reflex nationaliser Jeremy Corbyn as leader, sound a lot more interventionist than governments of both parties since before Thatcher. But it would be a big break with precedent.

The UK government’s apparent new plan to resolve this problem was floated in that noted journal of technical policy analysis, the Spectator magazine. Britain would have the right to diverge on LPF issues, but the EU could apply tariffs in response to restore a balance of competitiveness. The EU might have to take it to some kind of arbitration first, similar to the WTO/preferential trade agreement model. Or it could be done unilaterally, with Brussels imposing duties as it does with antidumping and antisubsidy actions, presumably subject to dispute settlement afterwards. (Recall the classic gag by the American comedian Emo Phillips: “I asked God for a bike, but I know God doesn’t work that way. So I stole a bike and asked for forgiveness.”)

This mechanism has the advantage of speed, particularly if it can indeed be used like trade defence measures, and the ability finely to calibrate a response. Essentially it will give structure to working out an understanding over trade-offs, either explicitly discussed ex ante or emerging ex post. “You want to do X? It will cost you Y.”

The problem, though, is one typical of trade dispute settlements. It requires a certain level of common approach and trust. The system might be able to cope with a limited and carefully calibrated degree of divergence — an increase in tariffs of a few percentage points on the exports of British steel, for example, in return for cutting them a bit of slack on carbon targets.

But what if the UK really wants to march off in the direction of massive deregulation of environmental standards or huge trade-distorting government subsidies? Enthusiasm for those is not unknown on the right of the Conservatives or the left of the Labour party respectively. You can imagine a state of permanent resentment and litigation — and uncertainty for business — as the EU continues to crank up the cost of divergence and the UK tries to litigate to stop it or ploughs on regardless.

As we have discovered with China in the WTO, trying to use trade rules and dispute settlement fundamentally to alter the economic direction of a partner country is extremely hard. Trade deals, even with a unilateral tariff mechanism, are never going to be as swift and binding as the rules of the Single Market. (From the UK’s view, that’s kind of the point.) Dispute settlement is really there to fix difficult cases by arbitration within an agreed framework, not really to establish basic principles through case law. If the UK and EU try the latter there are going to be some fun discussions about the role of precedent in trade arbitration, as there have been with the US criticisms of the WTO.

And there we have it. A potential solution to one of the most difficult issues in Brexit. But one that presupposes that the mutual antagonism and accusations of bad faith over the past few years are temporary and reflect a tough exit negotiation rather than being a permanently poisoned relationship. It’s not exactly a dead cert, is it?

Charted waters

The US economy may be opening up, but demand for consumer products was still very low in the first half of June, with cars and clothing imports down by a third from the same time last year — only a slightly less steep annual fall than for the month of May. There was some uptick in household appliances and consumer electronics though, where imports were actually higher in the first half of the month on an annual basis.

Tall Tales of Trade

This is more a “told you so” rather than an attempt to expose a new myth to derision, but there’s no point being right if you can’t be smug about it occasionally. Remember two weeks ago we cast doubt on the UK’s assertions that its bilateral PTA with Japan was going to be a bold step beyond the EU’s existing deal? The great Robin Harding, regular Trade Secrets contributor and massive econ-brain, this week revealed Japan wants a deal with the UK in just six weeks to get it through the Japanese parliament by the end of the year. That very likely means no new agricultural market access for the UK, or any other fundamental changes. That’s the thing with needing to get trade deals with bigger partners done in a hurry with political pride hanging on them: you more or less let the other side dictate the deal.

Don’t miss

Can the EU’s carbon border tax work for farming? The theory may be sound but applying it to agriculture will be hard, writes Alan Beattie in an FT special report on sustainable food and agriculture.

Read more

British manufacturers have raised fears the UK will be flooded with cheap, poorer quality goods if Washington forces companies to submit to US standards as part of the negotiations on a US-UK trade deal.

Read more

India is delaying the clearance of Chinese imports a week after 20 of its soldiers were killed in a border clash with People’s Liberation Army troops — a move that has infuriated business groups.

Read more

Tokyo talk

The best trade stories from the Nikkei Asian Review

South Korean trade minister Yoo Myung-hee, who announced her bid yesterday for director-general of the World Trade Organization, said her candidacy would not affect South Korea’s export control dispute with Japan.

Read moreNikkei Asian Review takes a look at how Trump’s fixation with China undermined the US coronavirus effort, with the White House shutting out the world’s largest supplier as hospitals scrambled for medical gear.

Read more

Comments