Demographic time-bomb: Finland sends a warning to Europe

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In a new building wedged between the sea and a power station in north-west Helsinki, a closely watched experiment in elderly care is taking place. A group of about 30 people aged over 60 are eating dinner at a housing development called Kotisatama, whose facilities include two saunas, a roof terrace and an exercise room for circuit training and pilates.

But there are no staff. Kotisatama is a community house in which both single elderly people and couples live together and share the chores. “The main purpose of this house is to keep us active,” says Leena Vahtera, a 72-year-old resident and chair of the project. “This is not a nursing home.”

Her husband died in 2007 while her two sons have their own families. “I didn’t want to be a burden to them. I saw how my own mother was so lonely. We are sure that the state can’t provide the services that old people may need one day. We want to make decisions on our own lives,” she says.

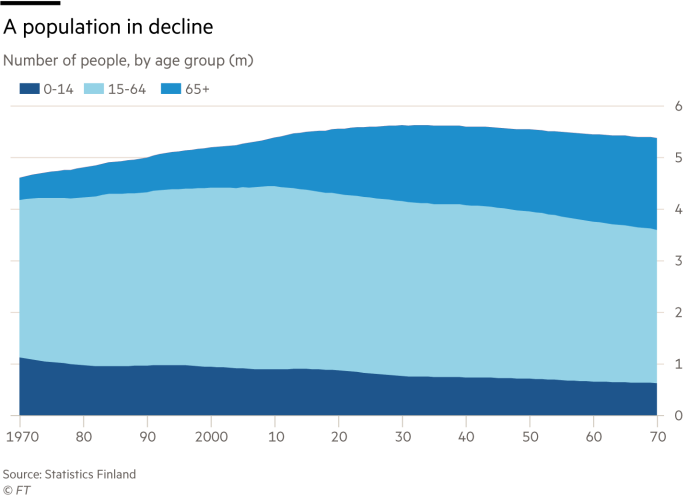

The Kotisatama development is attracting a lot of attention because Ms Vahtera is part of one of the most rapidly ageing populations in the world. Among rich, industrialised countries only Japan and South Korea have had larger increases in recent years than Finland. While people over 85 represented just 1.5 per cent of the population in 2000, today they are 2.7 per cent, and by 2070 are expected to be close to 9 per cent.

Finland has been discussing what to do about its demographic problems for almost two decades, pushing reforms of its healthcare, local government, social care and pensions system. “Finland is a rational country. It’s something we have taken very seriously and we have looked decades forward — something not done in most countries,” says Ilkka Kaukoranta, chief economist at SAK, Finland’s trade union confederation.

Yet finding answers has proved nigh on impossible. Finland’s three-party coalition government collapsed last month over its failure to pass landmark healthcare and local government reforms before an election on April 14. The only long-term issue related to demographic trends that has been addressed in two decades of trying has been pension reform.

For Europe, Finland may be a warning about the intractable political problems that lie ahead. Its population is ageing faster than any other European country, although Germany and Italy will have bigger peaks of older people later on this century. The lesson from Finland may be that trying to make health and elderly care costs sustainable involves the types of political choices few governments are willing to make, raising questions about long-term economic growth and the health of public finances for increasingly cash-strapped governments across Europe.

While parts of the rest of Europe face what researchers at the Robert Schuman Foundation have called “demographic suicide”, the lessons from the Finnish experience are complex. Breaking the omertà around ageing — as the foundation argued for — has not particularly helped in Finland. “In European terms we have been preparing early but only a little has been done,” says Marja Vaarama, a professor of social work at the University of Eastern Finland.

Join the Europe Talks project

The Financial Times is collaborating with 16 news organisations for an experiment called Europe Talks, where we connect thousands of Europeans for face-to-face conversations across borders. Would you like to be involved?

The country is a vivid demonstration that demographic change forces hard choices between politically unpalatable reforms and potentially deep belt-tightening. As a senior eurozone official remarked at the height of the 2010-11 sovereign debt crisis involving Greece, Spain, Portugal and others: “If I want to get really depressed, I think about what we’re not talking about at all — the ticking demographic time-bomb.”

“It’s very demanding and very tough to do. There are so many practical problems to be solved. Europe is going to be even messier,” says Timo Soini, the outgoing foreign minister, speaking before the government’s collapse. Another top Finnish policymaker is blunter: “This is a serious blow to our credibility as a reforming nation. But if we can’t do it, what hope have the rest?”

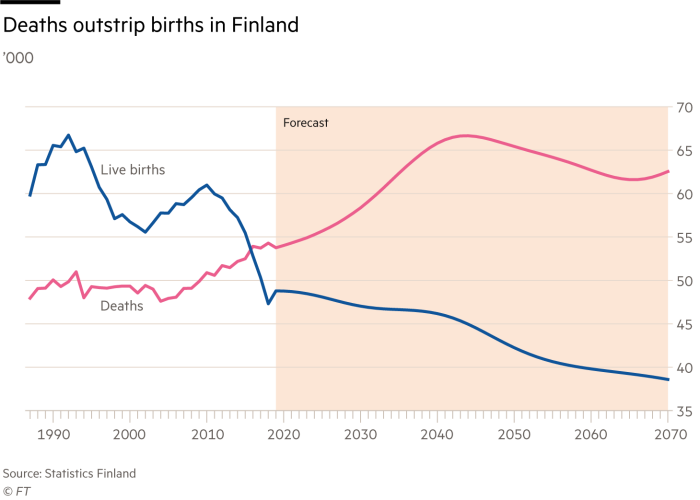

Finland’s ageing population results from the baby boom that followed the 1939-40 Winter war with the Soviet Union and the second world war. Life expectancy has steadily risen and now lies at about 79 for newborn boys and 84 for girls. Over 65s passed the under 14s as a bigger age group a few years ago and by 2070 they are expected to be about a third of the population — compared to just over half for people of working age and about 10 per cent children.

“This is the main engine to the structural imbalance of our economy and our public finances,” says Kai Mykkanen, Finland’s interior minister. In recent years, Finland has started to calculate its so-called sustainability gap — the long-term difference between government spending and income that will be aggravated by an ageing population. For now, it is about 4 per cent of gross domestic product.

Successive governments in Helsinki have tried to narrow this gap with a broad array of policy proposals. Major reforms of the pensions system were passed in 2001 and again in 2014, and most experts now think it is on a solid financial footing.

But reforming health and social care has proved far more difficult, defeating each of the last three governments. Part of the problem is that health and social care are the responsibility of municipalities and these range massively in size, from the largest — Helsinki — with more than 600,000 inhabitants to the smallest with just 92. Providing a full range of services is increasingly difficult for many of the smaller municipalities and waiting times are often long.

The current government tried to combine a shake-up in local government with the health and social care reform package. The problem was that the two main parties in the coalition come from completely different constituencies. The Centre party of prime minister Juha Sipila draws its support from predominantly rural areas while the National Coalition party of finance minister Petteri Orpo are more focused on the big cities.

Healthcare experts suggested having five or six regions, centred around Finland’s biggest cities. But this was anathema to the Centre party, which instead proposed 18 newly formed counties.

It is a painful lesson for the rest of Europe as political fragmentation is increasing across the continent, making government formation in many countries highly difficult and complicating the chances of changing such sensitive policy areas as healthcare. “It’s hard to do reforms with multi-party governments,” says economist Olli Karkkainen.

The final reform proposal was highly complex and ended up drawing opposition from many quarters including complaints that it went against Finland’s constitution. The reform ran out of time before parliament was dissolved for the national elections. The Centre party in particular is expected to be heavily punished in the polls, in large part due to resentment over the healthcare issue.

The next government in Helsinki is expected to make another attempt at reforming health and social care, perhaps by breaking it up into its individual parts to try to make it more manageable. But a three- or four-party coalition is likely to be needed, complicating matters further. All this could weigh on Finland’s public finances, with credit rating agencies warning they may take negative action if reforms do not materialise.

Economists at the Finnish central bank looked into the similarities between their country and Japan — with Finland’s population in 15 years’ time expected to look like Japan’s today — and concluded: “If decisions on reforming the structures of the economy are postponed far into the future, in the light of Japan’s experiences this may result in reduced growth and employment, with consequent high costs.”

Beyond the pure politics and economics, experts in Finland say the debate on ageing needs to be rethought. Prof Vaarama says that it is wrong to classify all people aged over 65 as “old”. She argues true old age starts at 80-85. Before that, people could still be working and be consumers in the new so-called “silver economy”. “Society doesn’t yet understand what longevity is. We should look at how we can benefit from this population,” she adds.

Finland has switched from prioritising institutional care of the elderly to trying to keep them at home for as long as possible. Prof Vaarama says this is good but only if they get sufficient care: “There are a lot of complaints that they do not have enough personnel, they just do 15 minute visits.” She adds that simple policies such as better physiotherapy at home could keep couples together and stave off loneliness, which is becoming an increasing problem.

That was the thinking behind Kotisatama, where 83 people — with a median age of 72 — live in 63 apartments. There are 18 couples, four single men and the rest are single women. Each week, groups of six take turns to cook and clean.

“It keeps our heads and legs in good condition. It’s better to get old together,” says Ms Vahtera. She adds that the residents are well aware that resources are limited at both local and national government levels: “In the long term, buildings like this save them money.”

Juha Metso is a former doctor and now head of social and health services in Espoo, a city just west of Helsinki that is home to big companies, such as Nokia and Angry Birds maker Rovio Entertainment. Espoo’s The population aged over 75 is growing at about 5 per cent a year .

But Mr Metso says he does not see an ageing population as “a problem”. “It’s a joyful result of better living conditions, services, better nutrition. The older people in Espoo are VIP citizens and we need to take care of them,” he adds.

He argues that municipalities need to adapt to the needs of citizens, offering more home services — including being available 24 hours a day — as well as more meeting places for the elderly such as in libraries. “The current discussion is more about change than how do we create better health,” he says.

One example he cites is elderly women who suffer hip fractures. By operating faster and starting rehab straight away, Espoo managed to cut their hospital time by a third and reduce the death rate by 6-7 per cent. The reduced need for beds — 45 — was equivalent to a new maternity ward.

Seen from the cities, the solution is clear. Both Mr Metso and Kari Nenonen, the former mayor of neighbouring Vantaa, say services need to be combined in rural areas, with smaller hospitals being closed. “You would have to travel further to get functioning services,” says Mr Metso.

But the political trouble of such a solution is easy to see just across the border from Finland. A maternity ward was closed two years ago in Solleftea in northern Sweden, forcing expectant mothers to drive 100km to the nearest alternative. A year later, support for the ruling Social Democrats was decimated in the town. “This is the problem: we know what needs to be done but doing it means you will probably not get re-elected,” says one Finnish policymaker.

Coalition-building: new government will have to engage with True Finns

Finland’s elections on April 14 are likely to be one of the more extreme examples of a European trend towards political fragmentation. As many as five parties could score about 15 per cent or higher.

The opposition Social Democrats lead the polls, benefiting from their ideological difference to the most rightwing government to rule Finland for decades. The Centre party of prime minister Juha Sipila are set to be the big losers of the vote, losing about a third of their support.

The wild card is the populist party True Finns. They entered government for the first time in 2015 but ended up breaking in two. Their government ministers all formed a new party, Blue Reform, which is set to sink without trace at these elections. But buoyed by the fallout from a sex abuse scandal in the Arctic involving several immigrants, the more hardline version of True Finns has gained support and could finish in second or third place.

One dilemma for the other parties is whether to exclude True Finns from power as has been done with the Sweden Democrats next door. But Finland has a tradition “of co-opting difficult politicians”, according to Risto Penttila, a businessman turned candidate for the centre-right National Coalition party.

He says the election is a peculiar one because it is not about “debating the really important issues”, pointing to foreign policy, Europe and to some extent the economy. Instead, much of the debate has revolved around the True Finns and its opposition to immigration and climate change measures. Meanwhile the collapse of the healthcare reform overshadowed any credit the government could take for reviving what was a moribund economy when it took over in 2015.

Letter in response to this article:

Finland’s high taxes are sapping its birth rate / From Toni Malminen and Binga Tupamäki

Comments