Jaffa’s emerging designers add urban cool to ancient city

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

For much of the past century Jaffa has been overshadowed by its younger and louder neighbour, Tel Aviv. It wasn’t always so; Jaffa was once an important port and trading post controlled by the Crusaders and then the Ottomans, and in 1891 it housed the first railway station in the Middle East. Yet after 1909, when Tel Aviv was founded just to the north, Jaffa fell out of favour. As many Bauhaus-style buildings went up in Israel’s “white city”, Jaffa became a crime-ridden industrial district where few people chose to live.

Now Tel Aviv’s poor relation is enjoying a renaissance. “In the past 10 years, Jaffa’s design scene has developed significantly,” says Maya Dvash, curator of the Design Museum Holon, south of Jaffa. Designed by Ron Arad and opened in 2010, the museum is currently showing a retrospective of Japanese designer Oki Sato, founder of design studio Nendo (running until October 29). “When we first thought of establishing the museum, investors could see a reason for investing in art but not design. This is partly because the design market in Israel is relatively small and few people invest in it. Fifteen years ago, there were no design shops in Jaffa but now there’s a growing number.”

In the 1990s, artists and designers moved to Jaffa because it was cheap and offered big spaces, says Rona Meyuchas-Koblenz, founder of Tel Aviv design studio Kukka. Those who settled in Jaffa, particularly in the hip, bohemian Noga district in the north, did not mind its ramshackle buildings. “Noga has the right ready-made architecture for us — old workshops useful for carrying large equipment in and out,” says furniture maker Gilad Shahar, who co-founded his Noga-based workshop and gallery Craft & Bloom in 2015.

Saga is one of the new design shops in Jaffa. Founded by Lior Yamin last year, its high-ceilinged, raw concrete walls provide a neutral backdrop for the eclectic work of the 80 Israeli, mainly Jaffa-based designers he represents. The longer established Elemento was opened by designer Yossy Goldberg in Tel Aviv in 1998 and moved to Jaffa 10 years later. It sells furniture and lighting — including Mika Barr’s cloud-shaped lights — in a large space with vaulted ceilings and alcoves lined with retro wallpapers. “Our pieces blend modern, high-quality materials, such as woods, metals and richly patterned textiles, all with a 1960s and 1970s-inspired aesthetic,” says Goldberg.

Israeli design benefits from the country’s design schools, including Shenkar College of Engineering, Design and Art, just north of Jaffa; Holon Institute of Technology; and Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. In a sign that the scene is coming of age, the first Israel Design Week was held in Tel Aviv last February. Attended by 30,000 people, it showcased work by local designers and architects. Tel Aviv also plays host to Fresh Paint, an annual contemporary design and art fair.

Other factors lie behind Jaffa’s transformation. In the past decade, the municipality of Tel Aviv has invested more than 1bn shekels ($266m) in renovating Jaffa’s main sites and streets. Developers are overhauling old buildings and prestigious architecture has been created, including the 2008 Peace Peres House by Italian architects Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas. Next year the W Tel Aviv-Jaffa Hotel and Residences, designed by Ramy Gill and John Pawson, will open in Old Jaffa, a world heritage site. Boutique hotel Market House, which incorporates the ruins of a Byzantine church, opened in 2014 near Jaffa Flea Market, itself a trendy hang-out filled with vintage furniture shops, fashion boutiques and independent cafés.

Yet, with familiar irony, the artists and designers who helped make Jaffa desirable look set to be priced out of it. In north Jaffa and the Flea Market area, property prices have climbed 250 per cent in eight years, more than anywhere in Tel Aviv, according to research by Haaretz, an Israeli newspaper. At the top end of the market buyers pay Shk50,000 ($13,200) a square metre — hardly affordable for up-and-coming creatives.

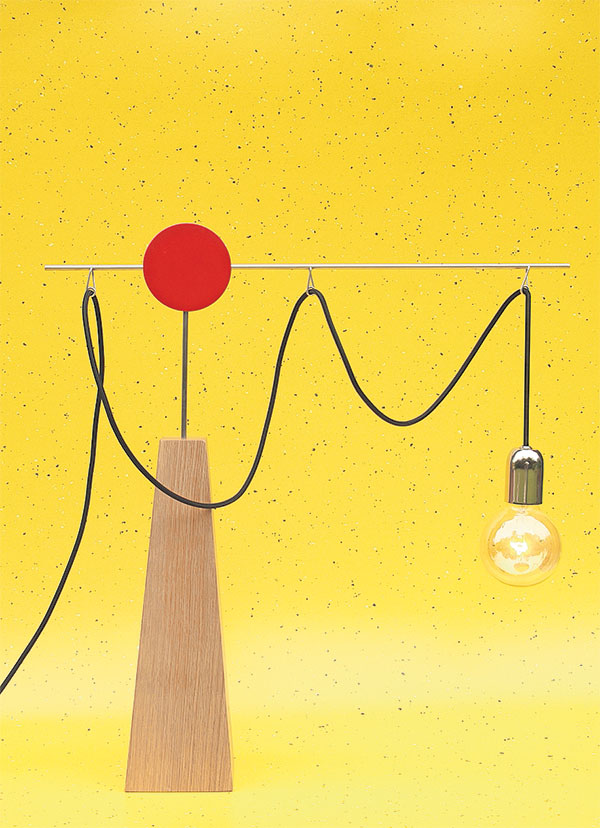

Local designers face other difficulties. “In Israel, unlike in Italy, say, there isn’t a big infrastructure of workshops specialising in crafts like cabinet-making or glassblowing,” says designer Asaf Weinbroom. His handmade lighting, fashioned out of wood, copper and glass — which often incorporates mechanisms that allow the lamps to swing like a pendulum or, thanks to devices such as ratchets and pulleys, be lowered or raised — is stocked by Saga. “This has led to a culture of self-sufficient designer-makers.” Weinbroom’s studio makes most of the components of his designs. According to Michal Mayo, a business consultant to mainly Tel Aviv-based clients in the design world, this is compounded by the fact that in Israel there are few financial incentives for starting a design studio. “Governmental bodies and non-profit organisations tend to invest in high-tech and science industries,” he says. “Also, there are limited suppliers of materials as demand for design is small.”

One reason Yamin decided to set up Saga was to give the local scene a boost. “I could see that many designers here needed a platform to sell their products,” he says. “My customers are mainly Israeli, but Tel Aviv’s designers usually want to sell their work abroad. They often exhibit at the Milan furniture fair.” Hilla Shamia, whose work he sells, has exhibited at Milan, Fresh Paint and at the London Design Festival. She is best known for her wood casting tables made by casting molten aluminium or brass on to uneven planks, creating their base and legs. The molten metal seeps into the cracks and chars its edges, making each table a one-off. Kukka launched two tables, called ABCD and O, made of dichroic glass and quartz, at the Milan fair this year.

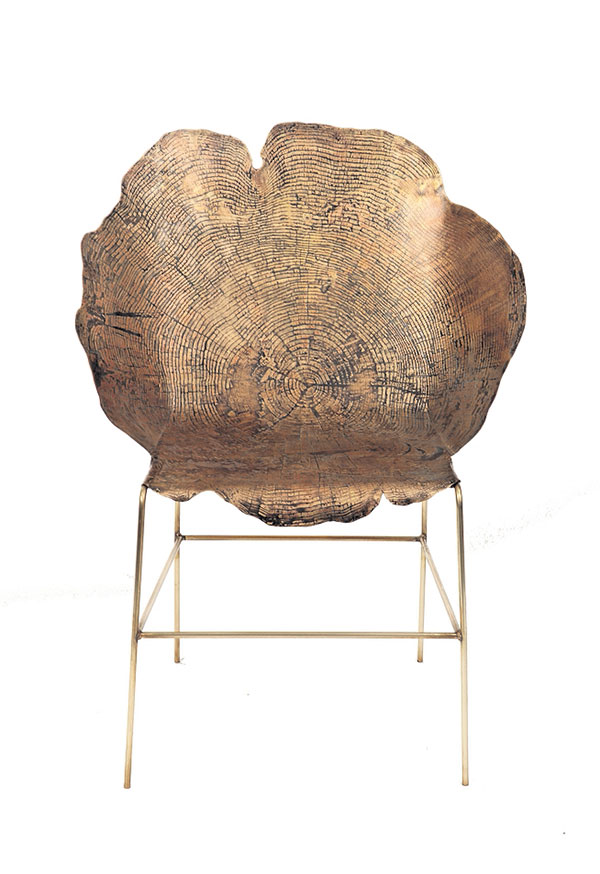

Another Saga protégée, Sharon Sides, is also fascinated by woodgrain. Her limited-edition Stumps collection is produced by photo-etching the ring patterns of tree trunks on to sheets of brass. The sheets are cut to make table tops or shaped to form chair seats. Meanwhile, Itay Ohaly creates vases covered with layers of paint in different colours, culminating in a black layer, which he scratches with abstract doodles to reveal different hues.

Ariel Zuckerman’s Street Capture collection of sideboards and tables also plays with chance. He fixed wooden boards to the walls of streets near his studio in Noga in an open invitation to graffiti artists. Once happy with how they looked, he removed the boards and converted them into one-off pieces. Another of his designs, Knitted Lights — illuminated orbs suspended in knitted tubes — is available from online gallery Matter of Stuff. Zuckerman says that Jaffa’s design shops, Design Museum Holon and the Fresh Paint fair help to “develop the country’s design market”.

Maya Dvash is also optimistic: “Designers are benefiting from the current globalisation of Israeli design. Although many designers live here, their work is successfully exported.” Some believe Israel doesn’t have a cohesive design identity because it is a relatively new country. Yet arguably this allows for greater creative freedom. “We always say our design is based on improvisation since we don’t have a long-established design tradition,” says Dvash. “This means we aren’t obliged to work in any particular way.”

Photographs: Alamy; Uzi Porat

Comments