The Ukrainian artists making work as acts of resistance

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Although Russia invaded Ukraine only a month ago, it has already produced artistic responses that show both steely determination and a particular sense of desperate irony, which characterises Ukrainian society, in the face of a dirty and dishonourable war.

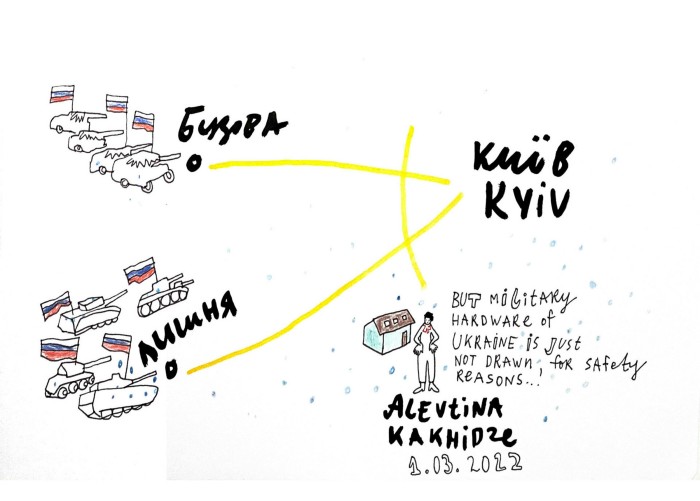

In a visual diary artist she publishes on Instagram, Alevtina Kakhidze has been depicting her everyday experiences and thoughts on military aggression since Russia escalated its preparations for war. In one entry shortly before the invasion, the artist — who has been featured at the Whitechapel Gallery and the Manifesta biennial — portrayed herself between gifts of arms and good wishes from friendly nations and a battery of Russian weapons.

Two weeks later, Kakhidze, who is based in Kyiv but originally from the occupied Donetsk region, drew herself and her home by the intersection of routes taken by the Russian tanks in their attempt to seize the Ukrainian capital.

“Ukraine Will Resist”, a recent painting on paper by the Lviv-based artist who works under the alias Kinder Album, depicts the war between Ukraine and Russia as a confrontation between humanity and machinery, nature and artificiality, vulnerability and strength — where the former wins. Ukrainian people are shown nude, but in a great collective effort to resist. Russia is a lonely armoured tank that fails to proceed because of the (deceptively) fragile human force it confronts.

But it is not only in the past month that Ukrainians have been making work about war and its many ramifications. Since 2014, when Donbas and Crimea were occupied by Russia, the country’s artists have been more political and engaged with documenting the war’s impact, changing their focus to resistance and art activism as they address issues of identity and opposition to the invasion. They have become more concerned about the topics of trauma, contested memory, displacement and violence. Kinder Album has exhibited work about the war in international shows such as Between Fire and Fire in Vienna in 2019.

Kakhidze, who has strongly spoken out against Russian aggression since 2014, says her art’s concerns shifted. “If before the war started I criticised the society of consumption, after 2014, I completely changed the focus. Unprotected shop displays in the windows became for me a sign of peaceful life.”

A plethora of Ukrainian artists have been dealing with the topics of humanity and bodily experience as resistance to war and the vision of Russia as a repression-machine. For example, in the project Demarcation Line, Vlada Ralko depicted the struggle over the line between occupied and non-occupied territories as a tension between an almost nude woman, standing for Ukraine, shedding light on a two-faced military figure enveloped in darkness and attempting to protect his ambiguous monstrosity with his uniform.

Her new work, “Dove of Peace Rapes a City”, mixing drawing and painting on paper, reflects the full-scale invasion, converting the same double-headed monster into Russia’s coat of arms, only with skulls instead of eagles, as it shells a Ukrainian city. Ralko says: “I have nothing to say about this situation, except I have a demand to close the sky and to send humanitarian missions to Ukraine . . . This is not a computer game; we are alive people, and we need not only a symbolic support but a real one.”

Similarly, in her 2020 project President of Crimea, which anticipated recent events, Maria Kulikovska cast iron bells with a police stick as the clapper. The casts were of the female members of her family: the bells merged her with her grandmother, her with her mother and her with herself. This was responding to how she could not visit her family and hometown in Crimea because of fears for her life after her art activism.

One day before the full-scale invasion, she made an unfinished resin cast of herself filled with bullets as a premonition. Now, Kulikovska has become a refugee again and has had to face the horrors of the war with her six-month-old baby, spending several days in a parking lot to avoid shelling, then “from time to time running up to the 21st floor to eat and bathe the child before the shelling would start again”. She has now left the country.

The war has brought new names to the surface as young artists’ initiatives become visible. Work by Kateryna Lysovenko is one of these fresh views, grasping the confusion of the first days of the invasion — she made it in one of Kyiv’s bomb shelters. The direct, naive message of the painting depicting a mother and a child making obscene gestures is the ultimate expression of the determination of Ukrainians to resist. The work merges the Christian symbolism of the Madonna and child with the female figure from “Liberty Leading the People” by Delacroix, embracing both humility and the strength of civilian resistance. Her work has recently been shown as a projection in Vienna.

Rather than depicting materiel or might, a new series of charcoal drawings by Nikita Kadan, The Shadow on the Ground, focuses on the fate of Russian soldiers who came to Ukraine for war but now face an eternity there. Kadan traces the moment of death when individuals become nothing more than a shadow, unnamed and unremembered, consumed by the Ukrainian soil, as a result of their own dehumanising actions.

As many artists are in bomb shelters or refugee conditions their production has slowed, and the broader artistic community is focusing on how to preserve newly created works that have mostly been shown on social media. The NGO Museum of Contemporary Art and the film-maker Zhanna Ozirna are among several groups that have launched initiatives to create archives of Ukrainian wartime art to give them the permanence their media lack.

The urgency of Ukrainian artists’ message is already reaching other shores. In Turin at the Castello di Rivoli museum, Kadan and Giulia Colletti have curated a show of film and moving-image work by Ukrainian artists, including some now in besieged cities and others who have fled. In a sign of the seriousness with which the art world is treating this, Kadan, who is in Kyiv, launched the project in conversation with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, who curated Documenta 13.

Art can neither prevent a humanitarian catastrophe nor shield civilians from the continuous shelling by Russian planes and rockets. It is, however, capable of making the crimes of the war visible, speaking loudly about them to the global community and raising the public’s spirit in the gloomiest moments.

Comments