Istanbul Biennial: best of times, worst of times

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When a country is in the throes of political crisis, what position should its cultural guardians take? To ignore the situation smacks of fiddling while Rome burns. To embrace it is to risk myriad ignominies.

Fulya Erdemci, the curator of this year’s Istanbul Biennial, chose the latter option. Her exhibition, entitled Mom, Am I a Barbarian?, took as its theme the role of public space in art and society. To encourage a rapport with Istanbul’s population, the Biennial would be free of charge and there would be displays in public spaces.

As such, it could not be more relevant to a city that has been rocked by civil protest all summer. Triggered by the government’s plans to develop areas such as Gezi Park that are dear to the city’s collective heart, the demonstrations ballooned into a discontent provoked by fears among secular Turks that the ruling AK party wished to Islamicise their culture. The government responded with tear gas and water cannons. Hundred of people were injured and several killed.

Erdemci and her team supported the protesters (her catalogue essay exalts “this feeling of incredible solidarity and joy”). Nevertheless, by the time the Biennial opened last week, questions that provoke controversy during peaceful times – who do you choose? whose money do you take? where do you install? – had became loaded with more tension than one exhibition could comfortably bear.

In truth, Erdemci made an effort to confront the complex systems of power that underpin the urban transformation that has radically altered Istanbul’s infrastructure. This spring, she instigated a public lecture programme with the aim of examining how “publicness can be reclaimed as an artistic and political tool in the context of global financial imperialism and local social fracture”.

Of course, without “global financial imperialism” the contemporary art world would struggle to keep its show on the road. Nowhere is this more true than in Istanbul, where the collecting habits of a handful of wealthy dynasties has fuelled an explosion in the art market that means the city hosts two contemporary art fairs (which have been battling it out in the courts), several hundred galleries and a clutch of privately owned museums. Inevitably, it is often the same families whose conglomerates profit from the modernisation of the city.

The Biennial does not escape association. Its chief sponsor is the Vehbi Koç Foundation, the cultural arm of one of Turkey’s largest conglomerates, Koç Holding. In truth Koç, which is ardently secular, has recently had government contracts cancelled and its rapport with the ruling AK party is fraught with tension.

Nevertheless, during the Biennial’s public programme, artists angered by the Koç connection disrupted a performance and filmed Erdemci’s reaction. Erdemci called the police and threatened to sue the film-maker, actions for which she later apologised.

Yet there is a sense that the Biennial’s reputation as a guardian of freedom has been compromised. Turkey under prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has done some appalling things but, during the Biennial’s opening week, it grated to hear rousing speeches about the artistic struggle for free expression at parties held in Istanbul’s most opulent homes, where the inhabitants enjoy wealth consolidated over decades of the brutal military-backed rule that preceded Erdogan’s victory.

Furthermore, this summer, film-maker and artist Kutlug Ataman alleged that art advisers to Omer Koç, one of Istanbul’s most important collectors and a vice-chairman of Koç Holding, had threatened to withdraw their patronage of his work because of a TV interview in which, in their opinion, he was insufficiently critical of Erdogan’s government. Koç instantly issued a denial.

Erdemci defends her sponsorship with Koç as “a device, a mechanism. [It’s like] you have a smartphone but maybe a child worker made them.”

Also problematic is her decision to abandon the plan to display art in public areas. “What does it mean to take permission from the same people who are suppressing [us]? This way, we are pointing out presence through absence,” is how she defended it to me. Yet the result is that her artists are now sheltered in the privately financed, non-profit cocoons of Arter and Salt, which are owned by the Vehbi Koç Foundation and banking dynasty Garanti respectively.

Inevitably, such a freighted back story threatens to crush the work itself. The Biennial’s main venue, the waterfront warehouse Antrepo, was particularly disappointing. The building is earmarked for demolition, a fate that should have made it ripe for a poignant swansong. But from the opening exhibit, a wrecking ball swinging against its façade that is the offering of Turkish artist Ayse Erkmen, a lack of imagination blighted the display. An uneasy cavern, Antrepo drowned the majority of work.

Art that blurs boundaries with social documentary can thrill but here the sheer number of complex, text-based projects rendered much of it flat, cold and overly analytical. From Gezi Park to Lima, New Jersey, Palestine and São Paulo, many pieces took the spectator on a world tour of urban change and its attendant social injustices. Yet the disconnected nature of the stories left the spectator bewildered rather than moved. Many artists deserved better. Consider, for example, the journey of the stone hand cast by Dutch duo Wouter Osterholt and Elke Uitentuis. The sculpture was inspired by the demolition, on the prime minister’s orders, of a statue in Kars, a city on Turkey’s Armenian border, that had been erected as a peace monument. Osterholt and Uitentuis wheeled their hand about Kars in a barrow, asking people for their opinions on the scandal, and casting their hands. These hands were installed on the site of the demolished sculpture, where they were instantly removed by police.

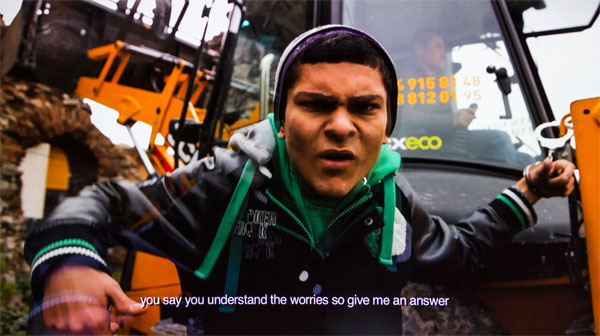

Also memorable was “Intensive Care” by Rietveld Landscape, a Dutch studio that had originally intended to install its work, a light that responds to human presence, in the Atatürk Cultural Centre in Taksim. Deprived of that chance, Rietveld simply scaled down its model and put it in a pitch-black space within Antrepo. After the cacophony of ideas outside, the quiet, poetic provocation of that flashing square stilled the mind and opened the imagination. Very different yet sharing the same potent immediacy was Halil Altindere’s film, Wonderland (2013), of Roma hip-hoppers voicing their lyrical fury at the destruction of their Istanbul neighbourhood.

Fortunately, the ratio of artists capable of conjuring poetry out of socio-politics increased at the show held in the Galata Greek Primary School.

Here, the outstanding piece was “I am the dog that was always here” (2013) by Berlin-based artist Annika Eriksson, a video of stray dogs exiled to the outskirts of Istanbul accompanied by a prophetic narrative – “They lived there and came and disappeared and now they are back”, “I can’t remember if those buildings are being constructed or taken down” – which captured the helplessness in the face of dispassionate power that has animated so much of modern Turkey’s history.

Artists who obliquely approached Erdemci’s theme mined deeper depths than their more literal peers. Elmgreen and Dragset, unable to realise a more ambitious public project, returned to a 2003 performance whereby young men sat at school desks writing their private diaries. To come upon these grave, silent scribes in a darkened room was to remember that without ethical public authority, private freedom is doomed. Upstairs, Argentine duo Martin Cordiano and Tomás Espina had recreated the replica of an immigrant’s apartment down to the Balzac novel on the table, the poster of Che Guevara and the crumpled National Geographic map on the wall. A clutch of broken objects – spectacles, crockery – betrayed the psychic fragmentation that is the price of exile.

Occasionally, a work breaks all the rules and triumphs anyway. The must-see of this exhibition was “Networks of Dispossession” on the top floor of the Greek school. A project by a collective of Istanbul artists led by Burak Arikan, it used a digital mapping programme to reveal the network of connections between state power and the business and media conglomerates – including Eczacibasi Holding, sponsors of the IKSV foundation that organises the Biennial – that are its partners in the development of the city.

These arid graphics brought to mind a line by the radical American poet Adrienne Rich, whose despair at the depredations wrought by capitalism on society drew her towards Marxist theoretics. “All kinds of language fly into poetry, like it or not.” Art’s battle to speak truth to power yet put bread on her makers’ tables is as old as civilisation. In Istanbul this year, it feels bloodier than ever.

Comments