Ecuador: a rainforest hotel

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

High above Ecuador’s cloud forest, I have a toucanet’s view of the jungle. I’m sitting on a two-person “sky-bike”, suspended from a cable, being pedalled by my guide Robby Delgado. Sometimes we soar above the canopy, sometimes we gaze down into a river-filled gorge, hundreds of metres below us, and sometimes the cable takes us in and out of the trees – just like a bird. Delgado can stop if we need to inspect a leaf, an insect, a bird’s nest. He can backpedal if he thinks we’ve missed something. We have extraordinary, intimate views of the inner forest – something few ever get to see.

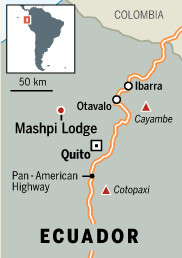

This is what Roque Sevilla, former mayor of Ecuador’s capital Quito, dreamt of when he wondered “what it must be like to fly like a bird”. The sky-bikes are his stroke of genius. They were inspired by a sketch he had seen in an old copy of Popular Mechanics and are designed to give visitors to Mashpi Lodge, the eco-hotel that he and some like-minded friends have built in the middle of 3,200 acres of protected forest, an experience that they’ll remember forever.

He hasn’t stopped there. Coming next – as soon as the paperwork is signed off – is a gondola, which you won’t have to pedal, but where you will sit as it moves at one metre per second over a different part of the forest. It will take some 30 minutes to cover 2km. In one direction you will travel high over the top of the forest, and in the other the gondola will go among the trees like a hunting hawk – each time giving a rare insight into this green and verdant forest.

All this is what makes a stay at the 22-bedroom eco-lodge so special. Tell your friends you are off to Ecuador and the betting is that they’ll assume you’re heading to the Galápagos, Darwin’s fabled islands. But few know that high up in the Mindo cloud forests – where the moist air from the Pacific hits the Andes – there is another magical place, one that is just as full of natural wonders and has only recently been opened up for travellers to explore.

Mashpi Lodge, which has won awards for its design by architect Alfredo Ribadeneira, is built almost entirely from steel and glass so that, as Sevilla puts it, “nature can be the star”. The rooms are large, airy and comfortable, the food plentiful, the thread counts on the sheets high and the showers full of power – but what makes it truly mesmerising is that wherever you turn there is the forest pressing up against the glass. Sevilla insists that this is much more than a hotel: “It is a vital linchpin for the preservation of this precious place.” The hotel and tourists provide work for the local population, who once had to chop down trees to live and who now have another source of income.

Sevilla started the project 11 years ago when he discovered that this paradise – with nearly 500 different birds, hundreds of rare orchids and many undocumented spiders, reptiles, plants and fauna – was being destroyed to make way for farming and building. More than 80 per cent of primary forests like this had already vanished, so he and some friends bought the land, originally just to preserve it. But then came the idea of tourism and they parachuted in Ribadeneira’s minimalist, transparent masterpiece so that visitors could view the jungle while “cocooned in luxury, safe from pumas, snakes, bugs and spiders”.

It is surrounded by a strange and sodden wilderness. The green-clad land rises and falls, as hills give way to deep ravines and gorges. With six metres of rainfall a year, all day long the skies are grey and the water drips. But there is a mysterious beauty in the changing patterns of the swirling clouds, in the way the lichen and liverwort festoon themselves round the trees, in the drama of the gigantic ferns and bromeliads, in the way the water drops off the leaves.

To the uninitiated, it looks like a vast, soggy forest where little moves and nothing happens, but a guide like Delgado, who knows the jungle intimately, opens up a new and fascinating world. With him, I tramp through mud, clad in rubber boots and a poncho (all supplied by the lodge), learning that most things here are “very small, very timid, very exquisite”. There are 19 types of hummingbird spinning round the lodge’s feeding station. There are 35 endemic birds, of which we spot just a few – though we hear them all the time, we catch only fleeting glimpses. But sometimes we see a pale-mandibled aricari with its huge curving beak, a moss-backed tanager or a rosy-faced parrot. Forest eagles and hawks, I learn, have stockier wings so that they can manoeuvre within the canopy and, from the butterfly pavilion where giant owl butterflies swoop around like bats, we look over the canopy and spot a swallow-tailed kite and a couple of hawks.

Delgado points out a walking palm tree, which puts out roots to enable itself to move nearer better light – an extraordinary adaptation since a mere three per cent of sunlight reaches the forest floor. For those who think all this sounds a little tame, he points out the dendrobatid frog – one drop of its sweat is enough to kill and its poison is used to tip the blow-darts used by indigenous tribes. Then there is the cyanide millipede, which, when threatened, emits a blast of cyanide – not enough to kill you but not something you’d want to smell very often. The 17 cameras dotted around the grounds reveal that there are pumas and ocelots, tayras (a bit like a terrestrial otter) and civets, but they are shy and difficult to spot.

At Mashpi one sees that in Ecuador the natural world is still revered. The mountains, rivers and waters were the churches of the Andean peoples. Volcanoes are gods and have a gender, and worship of the sun was everywhere. Today the rights of nature – Pachamama – are enshrined in the constitution and any citizen can petition on its behalf. And, since the natural world is what Mashpi is all about, there is no point in going if it doesn’t interest you. It is a special and different experience, but it isn’t for everybody.

For Sevilla and Delgado, though, Mashpi’s importance goes way beyond tourism. “We are helping”, says Delgado, “to protect a place with an incredible biological importance. Today about 60 per cent of new medicines come from plants. As a medicinal laboratory, it is vital …it is a heritage for all of mankind.” So there is a research station where resident biologist Carlos Morochz discovers new things almost every day. As the local wildlife recovers from the trauma of the hotel’s construction, spiders, orchids, frogs and birds emerge that need to be documented and studied.

For most tourists, three days in the cloud forest at Mashpi will be enough. After that, you may need to do a little sun worshipping of your own. I followed my stay at Mashpi with a visit to Hacienda Zuleta, near Ibarra, where guests get a real feeling for the history and lives of an Ecuadorean family – albeit of an extraordinarily privileged sort. Owned by the Galo Plaza family, often dubbed the Kennedys of Ecuador, it is run today by Fernando Polanco, whose grandfather and great-grandfather were both presidents of the country. The original house and stables were built in 1575 (the conquistadors arrived in 1532 and by 1565 most of the land had already been divided up) and the Galo Plaza family bought it in 1898.

In a staggeringly beautiful valley, surrounded by mountains and with views of the Cayambe volcano, the hacienda has 15 bedrooms. You can browse through the Galo Plazas’ library, hike up to a condor conservation project, ride Zuleteño horses (a fine crossbreed of Andalucian, English and Quarter stock), explore pre-Inca ruins and burial sites, and then slip back for seriously good food and Polanco’s entertaining tales of life in Ecuador. It’s worth it for the beauty of the drive from Mashpi alone – all around, the Andes soar above valleys with dramatic volcanoes (Imbabura, Cotacachi and Mojanda) thrusting their heads above the skyline. You should stop off in Otavalo, where you can buy textiles and leather work at the marketplace, and, more importantly, glimpse the life and culture of the indigenous Otavalan people.

Finally, back in Quito, I stayed at Casa Gangotena, a charming 31-bedroom hotel fashioned out of what was once an Italianate mansion overlooking Plaza San Francisco. It’s in the city’s old centre, which is being re-gentrified but not too much so. Behind the hotel are artisanal shops, food markets, dressmakers, museums and Spanish-built churches. Here you are surrounded by authentic Quito life – a perfect way to bookend an Ecuadorean journey.

——————————————-

Details

Lucia van der Post was a guest of Cazenove and Loyd. It offers a week’s trip from £2,610 per person, including two nights at Casa Gangotena in Quito, three nights at Mashpi Lodge (activities and full-board included), two nights at Hacienda Zuleta (full-board) and private transfers. Return flights from London to Quito cost from £750

Comments