Multi-ethnic UK town turns away from EU over migration

Satvinder was born in India, arrived in Britain at the age of three and has run a shop in West Bromwich for decades.

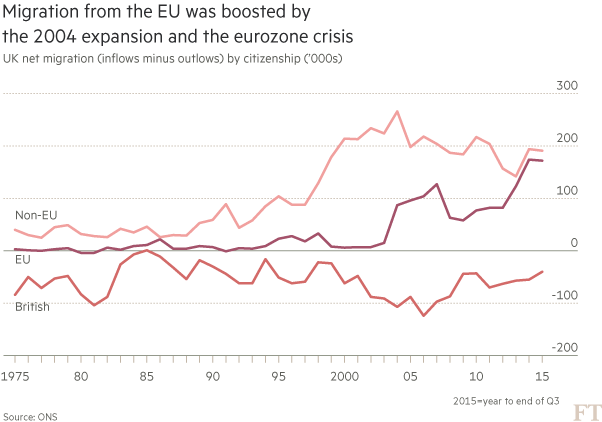

But he, like many others in this former industrial powerhouse, has little sympathy for more recent arrivals, whose rising numbers have gone hand-in-hand with a backlash against the EU.

“They’ve never paid into the system,” the quiet middle-aged man says of migrants from the bloc. “When my father came, he never claimed a penny in benefits. If he was out of a job one week, he was in a job the next week.”

Most economists say that EU migrants contribute more in taxes and national insurance than they take in benefits, but many voters register mounting concern at the economic and cultural impact of new arrivals.

Sandwell, the borough of which the town forms part, has experienced many previous waves of immigration since the 1960s. Yet it is one of the 10 most Eurosceptic areas in England and Wales, according to YouGov, the pollster.

Peter Durnell, local chairman of the UK Independence party, says migration is set to be the big issue in the June 23 In-Out referendum in British membership. “It’s the emotive one,” he says. “It strikes a chord.”

As of 2013, the last year for which full data exists, there were 6,000 Polish nationals in Sandwell, roughly on a par with the local Indian population. Since then, central Europeans have kept coming to a town already suffering from social and economic strains.

“At the moment I feel we’re being abused,” said Octavia Carrasca, a Sandwell resident originally from St Lucia, as she waits at a bus stop along a high street lined with half a dozen central European shops. “People are coming here and they’re getting things I never got.”

Such views have set much of the context for the EU referendum, but do not necessarily dictate voting intentions.

While the Leave campaign for the UK argues Britain could introduce restrictions on EU immigration without forfeiting access to the bloc’s single market, officials in Brussels and national capitals insist that no such arrangement is on offer if the UK breaks away.

“Attitudes towards immigration are the reason we’re having the referendum,” said John Curtice, senior research fellow at NatCen Social Research. “Attitudes towards the economy are what will decide the outcome.”

One challenge for the campaign for Britain to remain in the EU is that few residents in towns such as West Bromwich appear to associate the bloc either with concrete achievement or their own identity.

“I wasn’t born in Europe; I was born here — in West Bromwich,” said Irene Hooper, a retired secretary. “They want us to lose our identity, and it’s wrong.”

Maurice Evans, a greengrocer, complains that all the EU has ever done “is impose regulations”, adding: “Why are we so afraid of standing on our own two feet?”

The Black Country flag; a paean to the region’s industrial past, designed in 2012, is more often visible than the EU’s own starred offering. “The European flag is way down on the list,” said Keith Johnson, who has decided to vote Leave in June. “I’m not a European.”

Sandwell qualifies as one of the most deprived areas in the UK, according to the Office for National Statistics. The closure of nearby coal mines and steel factories hit the region in the 1980s; today, more than 6,000 families are on the waiting list for social housing.

The area remains strongly identified with the opposition Labour party: the party holds 71 of 72 council seats and all three of the main parliamentary constituencies.

The only non-Labour councillor is from Ukip, which won its first council seat in 2014, taking a white working class area that previously voted for the far-right British National party. The party is now looking to broaden its support.

————————-

UK’s EU referendum: full coverage and analysis

View the FT’s comprehensive guide to the vote on whether Britain should stay in Europe, with all the latest news, analysis and commentary from both sides of the debate. See more

————————-

“The core problem we’ve got is this racist tag,” said Mr Durnell, Ukip’s chairman, who argues that even first and second-generation immigrants are wary of new arrivals. “The Sikh community is a really big opportunity for us.”

Nigel Farage, Ukip’s leader, has said he will continue focusing on immigration, even though others in his party want a more upbeat economic message.

But misgivings about the EU go farther than Ukip.

Darren Cooper, the Labour leader of the town council, describes himself as “a bit Eurosceptic” and recently argued that Sandwell should not take any more asylum seekers until wealthier boroughs took their share.

Immigration “does put pressure on local schools, on local health services”, he said. “[But] what I’m worried about is that [the referendum] doesn’t become a vote on Europe; it becomes a vote on whether or not we have migrants . . . We’ve always had migrants, and they’ve integrated.”

Comments