Lunch with the FT: Ron Perelman

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

He has accumulated five marriages, eight children, a $12bn-$14bn fortune and countless legal bills from run-ins with family members, business associates and regulators. So it’s not a surprise that Ron Perelman collects restaurants, too. The pugnacious dealmaker has invested in establishments from Graydon Carter’s Monkey Bar in Midtown Manhattan to Harlem’s fashionable Red Rooster. He once fought to close the bistro Le Bilboquet because of “illegal” outdoor tables on his block, only to fund its move to a larger venue two streets away.

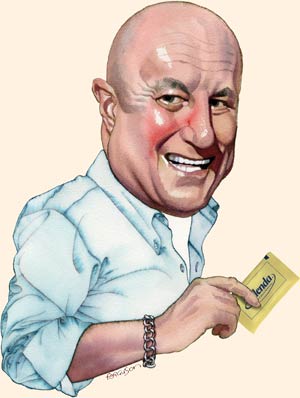

Perelman, one of the “barbarians” of the 1980s junk bond-fuelled takeover boom, has no stake in Michael White’s celebrated Italian seafood restaurant Marea but seems at home here. Maybe because he is a regular or maybe because its laminated wooden walls make the place shine like a billionaire’s well-polished yacht: it’s midday on a Friday and the 70-year-old looks ready to head for what he describes as his “little boat in the Mediterranean”, the 257ft yacht C². His pale blue shirtsleeves are rolled up, two buttons are opened to reveal a white undershirt and faint stubble spreads from his scalp to his chin. When I arrive he is at a corner table, watching the summer crowd walking along Central Park South with the wide, easy smile familiar from gossip column photographs.

Perelman’s diverse holding company, MacAndrews & Forbes, unites businesses selling mulch, military vehicles and scratch cards. He is also the controlling shareholder of the cosmetics giant Revlon. He has few insights into how a place such as Marea wins two Michelin stars, though. “I’m not a real foodie,” he confesses. “I like the theatre of restaurants more than I care about the food.” He finances restaurants to support friends or to boost their local communities, he says, and in 2009 backed an East Hampton margarita joint called the Blue Parrot with art dealer Larry Gagosian, singer Jon Bon Jovi and actress Renée Zellweger even though he hates Mexican food. The chefs there serve him grilled fish instead.

He wastes little time with Marea’s menu, despite putting on spectacles with comically thick round green frames to consult it. (“I just figured, if you’re going to get reading glasses, get them as funky as possible.”) I am just thinking that the $45 “business lunch” seems modest by Manhattan standards when Perelman orders the Dover sole, which commands a $55 supplement. I ask whether he wants a starter and he orders a salad, though without conviction. I skip the $275 an ounce caviar and pick lettuce soup with crispy frog’s legs, followed by gnocchetti with shrimp and chillies. “So you’re not Jewish?” he asks, when I have made my non-kosher choices. I ask whether I will offend him by eating shellfish and he assures me I will not. He keeps kosher at home, he explains, choosing fish or simple pastas when he is out.

Perelman, who was born in North Carolina and raised in Pennsylvania, describes himself as “a very religious, committed Jew”. He says he did not have an Orthodox upbringing but resolved to bring up his own children in a more observant manner after a moving first trip to Israel at the age of 18. Jewish education has also been a focus of his philanthropy, which this year has featured a $25m gift to his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania, and a $100m donation for a new innovation centre at Columbia Business School.

Music is another focus and this weekend he is in Britain to support a Carnegie Hall initiative to create America’s first National Youth Orchestra. After two weeks of training in New York, 120 musicians aged 16 to 19 will perform this Sunday at the Proms in London’s Royal Albert Hall. Valery Gergiev is conducting, and the US violinist Joshua Bell appears as a soloist. “I love music, and I think music for kids is particularly powerful,” Perelman says. Did you play growing up? I ask. He says he has been “a frustrated drummer” since he was 13, and keeps sets in New York and at his Hamptons beach house, insisting that any band playing on his property let him join them. As a result he has accompanied Al Green and Billy Joel, performed a New York show with Jon Bon Jovi and played one song with Rod Stewart at Madison Square Garden. Not that frustrated, then.

Perelman has also spent a fortune on art by Richard Serra, Cy Twombly and Roy Lichtenstein. Last year he traded lawsuits with Gagosian, a longtime friend, over “Popeye”, a $4m Jeff Koons sculpture. (Perelman accused the powerful dealer of cheating, alleging he had hidden a contract entitling Koons to 70 per cent of the profit from any resale. Gagosian called Perelman a deadbeat and a bully. A weary judge urged the two sort out their differences “at a cocktail party in the Hamptons this summer” before she had to write a decision but this has not happened).

Yet music, says America’s 26th richest man, is the art form that means most to him. “I’ve never gotten to the point of seeing the beauty in words,” he says. His preference for melody over lyrics is such that though he bid for both Warner Music and EMI in the past two years, he had no interest in the publishing arms that represent songwriters. “I would love to own a record company one day just because I think it would be so much fun,” he says, “but I don’t know what’s left.”

Our starters arrive. Perelman’s bowl of baby lettuces and radicchio is decorated with a green smear I assume is dressing. In my bowl, three crisp fingertip-length sections of what must have been a small frog’s thigh are arranged with small cubes of melon. Two dark, round leaves float up as the waiter pours in the pale green soup, like tiny (frogless) lily pads.

Some in the record industry dismiss Perelman as a trophy hunter dazzled by rock stars. He says he was “emotionally attached” to the idea of buying Parlophone, the EMI label sold this year to Warner’s Len Blavatnik, but he remained realistic enough about music business economics to have bid lowly earnings multiples. Music will always be in demand, he says, because “it’s background while we eat, it’s a way to dance, it’s a way to make love”.

…

As Perelman’s salad is taken away, barely touched, I eat the last few spoonfuls of my chilled soup and ask about dealmaking. Past investments include the film processor Technicolor; Golden State Bancorp, America’s second largest savings bank; and New World Communications, whose Fox TV stations he sold to Rupert Murdoch in 1994 for $3.6bn. Only a few targets, such as Gillette in the late 1980s, have evaded him.

A generation ago, he explains, “what you had was a very lazy managerial elite”. The takeovers made possible by the easy financing of the 1970s and 1980s were “to the benefit of American enterprise”, he insists. But, after five post-crisis years of corporate belt-tightening, there are few easy pickings left. Most deals Perelman looks at now are small “bolt-ons” to businesses he already owns.

I observe that nobody now is writing books such as Barbarians at the Gate, the 1990 study of a ruthless leveraged buyout. Did dealmakers get dull? The chunky silver chains on his right wrist rattle as he taps a packet of Splenda sweetener on the table and answers: “At one point we were doing stuff that was new and different and unique. That’s not the case any more. The techie guys are doing that now, so they’re the ones getting the attention. What we’re doing is pretty mundane stuff. What the techie guys are doing is …change-the-world stuff.”

Perelman sounds more confident about his philanthropy changing the world than his businesses. Revlon has championed breast and ovarian cancer programmes and Perelman’s $2.4m gift funded the development of the breast cancer drug Herceptin. He also has high hopes for another breast cancer drug in development. If it works, “we’ll have almost single-handedly funded the end of breast cancer. That would be pretty cool, right?”

His sole arrives, accompanied by grilled asparagus spears and a charred lemon half. My gnocchetti are light, the flavour of the red shrimp clear through the spicy sauce. The conversation turns to Perelman’s fifth wife, psychiatrist Anna Chapman. “She is so fantastic,” he says, beaming, before giving me the 20-second version of his epic personal life. “I married [real estate heiress Faith Golding] very young, then I met Claudia [Cohen, a Page Six gossip columnist], who from the day I met her until the day she passed away was my best friend in the world, then I was with two …interesting women,” he says, smiling as he glosses over his marriages to political activist Patricia Duff and actress Ellen Barkin. “And then I met Anna.” The couple married in 2010.

Perelman, who has reportedly spent more than $138m on four divorce settlements, says he does not regret any of his marriages, “even though some were very, very difficult”. This does not quite capture the bitterness with which some of them ended. In 1997 he began a $15m child custody battle with Duff. Perelman – who says he had to decide whether to worry about the bad press or be a good father – won but hostilities flared again in 2008 resulting in a fresh settlement.

Yet, each time, he married again. In Anna’s case, he says, “she wanted children and I would not say no to a young woman who wanted children. I think if you’re going to have children you should be married.” So at 70 and with 10 grandchildren, Perelman now has two young boys under three years old. “The one-year-old slept with us last night. It’s such a treat. It’s such a miracle,” he beams, sounding more forgiving than I am after my bed is invaded by infants.

…

Doing business runs in the Perelman family. Raymond Perelman, the son of a Lithuanian immigrant who had founded American Paper Products in 1916, sounds like a prototype of his son, building the Philadelphia business into a paper, metals and freight group through acquisitions and an exacting approach to business and family. Perelman says his father, now approaching 96, “works every day and still has his eye on pretty girls”.

Ron was sweeping floors in his father’s factories, aged 12, and after university he became a foundry manager. By 34, he was chief operating officer but wanted the title of president, which his father would not give up. Perelman split from his father, turning to his first wife and a bank to fund his first acquisition. That deal gave him 40 per cent of a jewellery group trading far below book value. By splitting up the company and riding a rise in diamond and gold prices, he made his first independent fortune.

I finish my pasta and see that Perelman has eaten less than a quarter of his sole. Even so, when the waiter comes by, he says: “All done, thank you. Perfect!”

He orders an iced cappuccino and I ask for a macchiato before asking why he still works. “I work, like my father did before me, primarily for my family,” he says, but he adds that as he has grown more religious he has come to believe he has been blessed and has a duty to give something back.

Will he be working at 96? “I hope I’m doing it at 110,” he shoots back. His youngest son will be in his forties by then, and I ask whether he wants his children to work for him. “My [oldest] boys both worked for me. They didn’t like it,” he replies. “At first I was disappointed …but I grew to be happy that they’re happy.” One daughter is now looking at “technological add-ons” for his businesses, he adds.

He personally doesn’t use email, has no computer and sends no texts, he says, looking me in the eye as he adds that he prefers to look people in the eye. “You look around this restaurant and half the people are doing something except what they should be doing.” A glance at the number of iPhones being consulted by Marea’s well-heeled clientele confirms he has a point. How does he run his businesses without a constant stream of digital updates? “I have a lot of secretaries,” he says with a smile, before taking a call on his old Nokia telephone.

Why, I ask, does he keep ending up in court? Last month alone, Revlon and MacAndrews & Forbes made separate settlements with the SEC and the Justice Department respectively, while one subsidiary sued Michael Milken, who funded Perelman’s Revlon takeover. Last year he was involved in fighting Gagosian as well as Donald Drapkin, a business partner of 20 years.

Does he enjoy litigation? “I hate it,” he says. “I guess by the nature of my personality I have a hard time dealing with either being taken advantage of or being f***ed over. That is especially true when it’s being done by somebody close to me.” Only a fraction of his deals have ended in acrimony, he stresses. And the main downside he sees is the bad publicity. “I hate the press,” he says but he will take any opportunity to get his side of the story out, “which is why I’m sitting here with you”. Pleased to have been of service, I say, wryly. He chokes on his cappuccino.

After 90 minutes at Marea, business – or his yacht – is pressing and Perelman reaches for his glasses and University of Pennsylvania baseball cap and says goodbye. I notice that two coffee cream puffs sit untouched in the middle of the table, topped with brown sugar and a fleck of gold leaf. I pop one in my mouth as the waiter comes over and asks: “Is the cheque you or Mr Perelman?” I explain that I must pay, and he hands over the bill – $180 before the tip. The maître d’ follows, saying anxiously: “I’m going to get in trouble with Mr Perelman for letting you get the meal.” My guest is always a light eater, he confirms, lest I get any impression he did not enjoy his meal: “The fish was perfect, I can assure you.”

I eat the second cream puff. Maybe it will make amends for the wasted sole.

Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson is the FT’s media editor

——————————————-

Marea

240 Central Park South, New York

Iced Tea x2 $9.00

Prix Fixe x2 $90.00

Sole (supplement) $55.00

Macchiato $5.50

Iced cappuccino $6.00

Total (inc tax and service) $210.19

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Don’t invite people with poor manners to lunch / From Mr James Atkins

Comments