Global groups pay a heavy price for China’s slowdown

Simply sign up to the US & Canadian companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Markets around the world have been roiled this month by uncertainty about China’s economic growth and the ineffective reaction by local authorities to the turmoil.

While traders have taken most of the pain so far, there is a wider — more insidious — impact that is spreading to companies far behind China’s shores.

With the country’s economy growing at its slowest pace since 1990, according to official statistics released on Tuesday, some industries, including mining and cars, are far more exposed to the slowdown than others.

However, few are likely to escape some reshaping of their future prospects as a result.

Outside Asia, Latin America is particularly vulnerable with 10 per cent of its exports headed for China, and Europe will feel the pinch more than the US.

“China has set off a major correction and it is going to snowball,” warned Andrew Roberts, head of credit at Royal Bank of Scotland, in a recent note.

Turbulent financial markets rarely have a direct impact on the corporate sector in China because local companies largely do not fund themselves there.

But the perception that the market turmoil is beyond the control or influence of the Chinese authorities will, say analysts, influence confidence and, thus, future decisions over when and where to invest.

“What we are finding out in recent weeks is the indirect impact which goes via the confidence effect,” says Marie Diron, an analyst at Moody’s, the credit rating agency.

Market performance also reflects more profound concerns about China’s future growth. It is no longer a matter of debate whether the economy is slowing, but of measuring its effects.

China consumes about 50 per cent of some raw materials, and so far, its economic slowdown has therefore had the most acute impact on commodity-related sectors. For many companies, the most immediate effect is on demand. But the over-exuberant investment that has characterised many commodity sectors, as well as the shipping industry, will take years, not months, to unwind.

“For the over-invested global industries, there is a real supply imbalance, much of it relating to China in steel, metals and mining, oil, and both container and bulk shipping,” says Paul Watters of Standard & Poor’s.

The regional impact is also broad. Europe’s direct trade exposure to China is moderate but, if re-exports are included, says UBS, the exposure is almost doubled. China buys about 8 per cent of the EU’s exports, with Germany’s share by far the highest, followed by Finland, Austria and France.

Germany’s auto companies derive between 15 and 30 per cent of operating earnings and cash flow from Chinese sales. Analysts also warn that the impact on manufacturers and suppliers is obscured by the number of joint ventures through which western companies operate.

“Lots of European and US suppliers are operating in China via JVs so the impact may be diffused or delayed,” says Ms Diron.

Specific companies are also paying the penalty — even if only temporary — of their big bets on China. Global Counsel, the political consultancy, estimates that half Volkswagen’s revenues are derived from the country. Cognac producers have also been hit by the Chinese government’s anti-extravagance campaign. According to UBS, Rémy Martin earns a bit less than a third of its operating profit in China, while Pernod Ricard has about 12 per cent.

There are also broader ripple effects. As China’s economy falters, so do those of its neighbours and trading partners, in addition to its suppliers. The most affected sectors in the region are oil, gas and chemicals, analysts suggest, but slowing Chinese GDP is also likely to reduce disposable income and thus, for example, affect demand for air travel and hotel rooms.

For many western companies China and the emerging markets in general have been a focus for investment in recent years — the one bright spot in a slow-growing world.

For Gareth Williams, an S&P analyst, the argument for investing in China has not been diluted by recent events. “It changes the balance of which industries, and makes [the decision] more complex,” he says. “But China is still growing at a relatively fast rate.”

Podcast

How fast is China really growing?

George Magnus, senior economic adviser to UBS, discusses how reliable China’s data are and what country’s leaders need to do to reassure investors

Other analysts concur that the gloom may be exaggerated. Lower oil and commodity prices, mainly driven by events in China, have helped many companies globally, particularly in Europe and the US. Meanwhile, China’s transition towards an economy more driven by domestic demand will not help mining companies — but it may help retailers.

“China’s transition towards an economy more driven by domestic demand should benefit consumer companies everywhere,” says Nick Nelson at UBS.

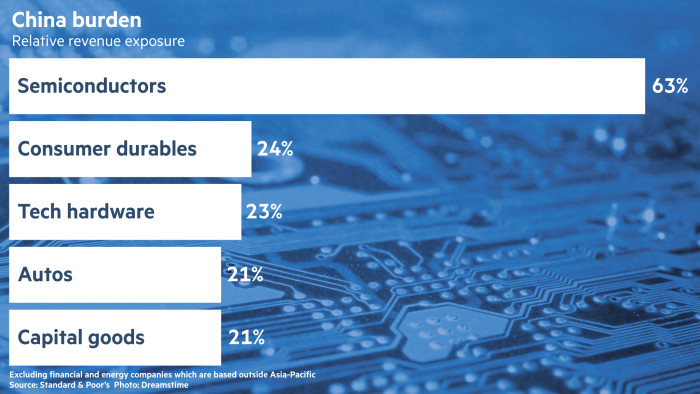

If commodities have been the hardest hit so far, other global industries are also highly exposed. Semiconductors, autos, consumer durables, technology hardware and capital goods are all feeling the pinch.

Semiconductor makers

At Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s annual results presentation last week, executives of the world’s biggest chip foundry came in for heavy questioning. The cause for concern: last month’s announcement of a $3bn investment in Nanjing, to capitalise on “the rapid growth of the Chinese semiconductor market”, writes Simon Mundy.

Chinese manufacturers accounted for nearly all the 48 per cent increase in semiconductor sales from 2009 to 2014. Semiconductor demand for non-Chinese companies, meanwhile, was shored up by surging demand for their electronic devices in the country — notably smartphones, for which it is now by far the biggest market.

But that growth in Chinese demand slowed markedly last year, casting a shadow over prospects for the global semiconductor industry. The biggest factor was a sharp contraction in the growth of the country’s smartphone market: having grown at a double- or triple-digit pace for five years, Chinese smartphone shipments may have grown by as little as 1.2 per cent in 2015 according to IDC, the research group.

This is largely a result of an increasingly saturated market. But Steven Pelayo, an analyst at HSBC, said the slowdown has been much faster than anticipated, suggesting a link to China’s broader economic deceleration.

“It really started in the fourth quarter of 2014 . . . by last July, semiconductor companies realised they were swimming in excess inventory,” he said. Memory chip “prices were falling apart for much of last year”.

Jian-Hong Lin, an analyst at Trendforce, added that slowing demand for high-end mobile phones contributed to the pressure on the industry. The market share of premium smartphones, which have the most valuable semiconductor content, fell from 18 to 16 per cent last year.

Despite this tailing off, demand for semiconductor-powered products is substantial. Chip imports amounted to $241bn in 2014, more than any other category including oil. The government is pursuing a Rmb1tn ($152bn) investment plan to strengthen domestic production capacity.

“Even though the environment may not be as good as before, China’s investment in semiconductors will continue,” said Mr Lin. “And every semiconductor company is still focused on China. They want to keep their position in the market there.”

Carmakers

Over the past decade, China provided sunny skies for the world’s automakers, as the likes of Audi, Porsche, BMW and Mercedes-Benz became used to selling lots of cars and charging large sums for them, writes Andy Sharman.

But clouds rolled in last year and foreign brands across the price spectrum felt the impact.

A crackdown on ostentation hit the likes of Bentley and Rolls-Royce, whose sales fell dramatically in China last year. Big fluctuations in the stock market diverted money away from car purchases, according to the local industry association, and overseas car marques were buffeted by a shift in consumer taste towards domestic brands and their cheap and cheerful sport utility vehicles.

Meanwhile, the slowdown in the wider economy put the brakes on overall car sales, and registrations fell for three consecutive months between June and August, sharpening fears of oversupply and price wars.

Then the Chinese government stepped in. Beijing halved the vehicle tax on cars with engines of 1.6 litres or smaller — a category that accounts for about 70 per cent of new vehicle sales in the country. That stopped the rot and car sales returned to solid growth from October.

The tax cut is due to run until the end of 2016, but analysts remain cautious. Their fears are less about sales growth than about the returns that can be expected by Volkswagen and General Motors, who each rely on China for more than a third of their operating profits.

Robin Zhu, analyst at Bernstein Research, says the retail prices are still headed downward for cars in China, with intense competition, dealer “overcrowding” and a boom in budget SUVs.

Tough new emissions rules due in 2017 will increase the costs for manufacturers selling in the country.

Contrary to the argument made by many auto executives, Mr Zhu sees little room for expansion in lower-tier urban areas, saying that most brands already sell vehicles in China’s “credible cities”.

Besides, he adds, auto stimulus rarely ends in long-term growth. “In most cases there is strong growth during the stimulus, but a meaningful pullback once the programme ends,” he says.

Luxury goods industry

One in three luxury goods are bought by the Chinese, a figure that makes the industry especially sensitive to developments within China. The economic slowdown and the government crackdown on corruption have hit luxury goods companies hard, writes Scheherazade Daneshkhu.

Hugo Boss pointed to “continued challenges” last week as it reported a double-digit decline in annual sales in China — its most profitable market. The company has suffered from overexpansion in the country and its stores are not all in the best locations, according to analysts at HSBC.

But Cartier-owner Richemont and the UK’s Burberry were more upbeat last week in quarterly trading updates.

The Swiss group said the rate of sales growth in mainland China had “continued to improve”, while Burberry said it was too soon to say whether its rise in mainland sales was the start of a sustained recovery.

The recent stock market turmoil in China “affects sentiment”, says Carol Fairweather, Burberry finance director, “so we focus on marketing innovatively. We can’t control what’s happening in the wider macro situation.”

Most Chinese luxury purchases are made abroad — as much as 80 per cent, according to Bain, the consultancy. But tourism patterns are shifting, with fewer Chinese visiting Hong Kong, where some feel unwelcome, while more are beginning to favour Japan. Burberry’s sales in Hong Kong dropped 20 per cent in the last quarter compared with the same period in 2014.

The terrorist attacks in Paris in November put many Chinese tourists off visiting the French capital, with both Burberry and Richemont reporting a fall in sales in the aftermath.

Claudia d’Arpizio, partner at Bain, says that even with a flattening economy, the desire for luxury goods among Chinese consumers remains strong. “Now the real question is profitability,” she says. “Brands have opened stores rapidly, sometimes choosing the wrong locations and many of them are in the process of resizing in terms of location and format.”

As China shifts from an export-led economy to one focused on consumption, Luca Solca, analyst at Exane BNP Paribas, sees new potential problems emerging. “The most important risk for luxury at the moment, in our view, is of declining import duties being replaced by higher luxury taxes. Bashing the rich sells well to the broader public and diverts attention away from the economy’s poor performance,” he says.

Global miners

The consequences of China’s slowdown for the mining sector have been direct and brutal, writes James Wilson.

The country rose from being an insignificant market to account for more than half of global demand for some commodities. As supply lagged behind, the resulting high prices sucked miners into a “supercycle” of ambitious investment.

Now global groups such as Rio Tinto, Vale and BHP Billiton are confronting much more subdued Chinese demand — just as many of the mines built during the boom years have begun producing for global markets.

The slowdown has been particularly hard on producers of commodities such as iron ore and coal, which were poured into building China’s cities, power plants and railway lines.

“Not only is China’s economic growth more modest, it has shifted emphasis from metals-intensive sectors — like infrastructure and construction — to consumer spending,” Sam Walsh, Rio’s chief executive, told staff as he announced a pay freeze this month.

BHP, the world’s largest miner by market capitalisation, says it no longer expects to invest in iron ore or coal.

If China’s consumer market starts growing rapidly again, some metals and minerals should benefit. Copper, for example, is used in cars and electrical goods. But in the meantime, large copper miners such as Glencore and Freeport-McMoRan are struggling. Diamond miners including De Beers, owned by Anglo American, have been caught out by slowing growth, which has cut the number of jewellery store openings in China and left the industry overstocked.

At the moment there is no market that can replace China, so groups are having to contemplate closing unprofitable mines to cut supply. But shutting down sites can be expensive, so there is a scramble to cut costs or sell off mines instead.

In the short term, both asset sales and cost cuts keep more mines in business, exacerbating the oversupply problem and putting more pressure on prices. But in the long term, miners’ desire to curb spending may lead to under-investment in production — and start another of the industry’s inevitable cycles.

Comments