Can protein help reverse memory loss?

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Everyone’s memory gets worse in old age, though the pace of decline varies between individuals. A few years ago many neuroscientists regarded age-related memory loss as an early manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease but that view is falling out of favour.

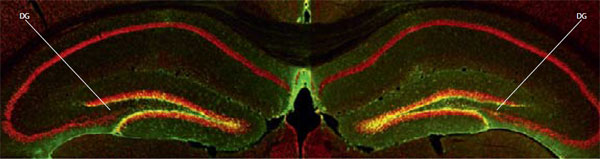

The strongest experimental evidence that age-related memory decline is a quite different condition has emerged from an ambitious study – using both postmortem human brains and living laboratory mice – at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, which is published in Science Translational Medicine. The research shows that a deficiency of the protein RbAp48 in the hippocampus is an important contributor to memory loss, which can be reversed – at least in mice.

“Our study provides compelling evidence that age-related memory loss is a syndrome in its own right, apart from Alzheimer’s,” says Eric Kandel, the project leader.

The Columbia scientists started by analysing the brains of people of different ages who were not suffering from neurological disease. They were looking for proteins that declined sharply with age in the dentate gyrus, a part of the hippocampus that plays a key role in memory. Having found RbAp48, they turned to mice experiments. When they genetically inhibited RbAp48 in the brains of healthy young animals, the scientists found memory loss similar to that in aged mice. When the inhibition was turned off, the young animals’ memory returned to normal. Then the scientists amplified the activity of RbAp48 in the dentate gyrus of old mice. “We were astonished that not only did this improve the mice’s performance on the memory tests, but their performance was comparable to that of young mice,” says Elias Pavlopoulos of Columbia.

“The fact that we were able to reverse age-related memory loss in mice is very encouraging,” says Kandel. “Of course, it’s possible that other changes in the dentate gyrus contribute to this form of memory loss. But at the very least it shows that this protein is a major factor, and it speaks to the fact that age-related memory loss is due to a functional change in neurons of some sort. Unlike with Alzheimer’s, there is no significant loss of neurons.” The next step will be to look for drugs that might enhance the activity of RbAp48 – and possibly fend off forgetfulness.

But, cautions Simon Ridley of Alzheimer’s Research UK, “People reaching older age may well have a combination of changes happening in the brain – both age-related and those involved in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Separating early changes in Alzheimer’s from age-related memory decline in the clinic still presents a challenge, but understanding more about the mechanisms of each process will drive progress in this area.”

——————————————-

Prepare for take-off

Analysis of fallout from the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in Iceland, which severely disrupted air travel in the spring of 2010, is clarifying scientists’ ideas about the way volcanic ash behaves in the atmosphere. The results will help aviation authorities to decide when it’s safe to fly after future eruptions.

The latest research, led by Bernard Grobety of the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, shows that the type of particle most likely to damage jet engines was the first to fall out of the Eyjafjallajökull ash plume. The Fribourg scientists analysed samples of the ash taken at different points on its journey across Europe, both in the air and on the ground. Their findings were presented at the Goldschmidt conference in Florence last week.

They found that crystalline particles fell out of the cloud more quickly than glassy particles of ash. “Since crystalline particles are harder and melt at higher temperatures, they are more harmful to jet engines than glassy particles,” says Grobety.

Much of the research since the Eyjafjallajökull eruption has treated the ash cloud as chemically homogenous, focusing on the concentration and the size of particles. The Fribourg research adds another layer of detail which could reduce the impact of any eruption still further.

“We’re already at the point where we can say that if the ash is at a certain concentration and a certain particle size, it poses no threat to aircraft,” says Grobety. “However, it’s possible that even at a higher concentration, if no crystalline particles are present, planes may still be safe to fly.”

——————————————-

The myth of marshmallows

Delaying gratification is hard – and becomes even harder if the desired object could be whipped away at any moment, writes Martha Gill. In 1972, in an experiment at Stanford University, 600 children were each handed a marshmallow and told that if they could go 15 minutes without eating it, they would then get two.

Those who waited went on to have greater success in life, and the test became an oft-cited classic (the Shrink and the Sage discussed it in the FT Weekend Magazine, August 24/25). If your child eats the first marshmallow, parents are told, you are in line for disappointment.

But perhaps we were too hasty. Researchers at the University of Rochester in the US looked again at the marshmallow experiment and found that if the adult conducting the test seems untrustworthy, even patient kids will not risk waiting for the second marshmallow. Refusing to delay gratification, it seems, can sometimes be the rational choice.

In the new version, before handing out the marshmallows one of two adults talked to the children. One promised art supplies which then never came. The other – more reliable – promised and then produced the supplies. This turned out to have a significant impact on the results. Over half the children who met the “reliable” adult managed to wait for the second marshmallow, but only one of 14 children in the “unreliable” group lasted the full 15 minutes.

“Kids are surprisingly capable of delaying gratification when they’re given evidence that doing so will pay off,” says Celeste Kidd, lead author of the study. “On the flip side, we also demonstrated that kids sensibly decide to indulge in an immediately available treat when the circumstance suggests waiting won’t get you anything better.”

Deep freeze

Using data from ice-penetrating radar, scientists at the University of Bristol have discovered a canyon – 750km long and up to 800m deep – beneath the Greenland ice cap.

More broadly, the authors suggest, living in an environment where adults are flaky may affect your ability to wait. Self-control is situational – the children were struggling not with appetite but with logic (is the second marshmallow really worth the wait?). But it is not just children: another recent study showed that it could be true for grown-ups too.

An online test conducted at the University of Colorado found that adults are less willing to wait for delayed rewards from someone untrustworthy, preferring a smaller, immediate pay-off. The authors wrote: “The struggles of certain populations, such as addicts, criminals and youth, might reflect their reduced ability to trust that rewards will be delivered.”

Says Kidd: “Together, the studies suggest that both little and grown-up humans consider the uncertainty involved in their current contexts – and that they use that information to make quite sensible decisions.”

The overturning of such a well-known study offers an interesting message, not only for parents but also for company leaders and politicians: U-turns, backtracking and sudden changes in rules come at a cost. And if your charges are eating their marshmallows too quickly, you might want to stop shaking your head over their lack of self-control and try being more reliable.

Comments