Latin America’s violent past in pictures

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

If what you want is certainty, words are easier to read than pictures. Photographs containing relevant words often fall short in visual mystery. Viewers naturally decipher a kind of internal caption, and then leave the picture – since they have every reason to think that having “got” the sense through the words, they’ve “got” the picture.

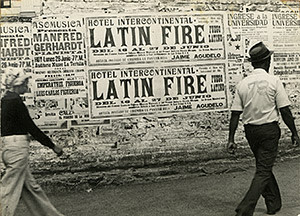

América Latina 1960-2013 is a magnificent, eye-opening and deeply moving exhibition but it never resolves that problem. There are more words in it than in any exhibition of photographs I have ever seen. Not in captions or accompanying texts, but within the pictures. Almost every body of work included is actively wordy.

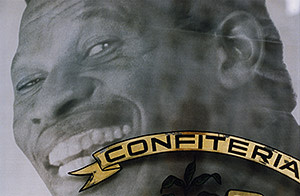

There are some images made with other things than words in which the photographic elements are really only illustration (the map-based works of Claudio Perna, for example). There are some texts written directly on the images (as the magnificent calligraphic screams of León Ferrari). There are far more texts found in the environment: graffiti and posters on urban walls, advertising, packaging. There are numbers of “extreme” words: a set of pictures by Rosângela Rennó mining a prison archive for studies of crude tattoos or an extraordinary 1970s video piece in which Letícia Parente made her comment on the commercialisation beginning then to gather pace in her country by stitching the words “Made in Brasil” into her own foot in black thread.

The curators don’t identify words-within-the-image as a specifically Latin American style of picture-making, but it is plainly the central current of the exhibition. This imposes a noticeable skew: in an exhibition of dozens of artists working across a very wide register (from performance to interventions in the landscape, to documentary and repurposing existing photographs and so on), made over 50 years across a huge geographical territory, we are invited to see only works in which overtly political or socio-political messages are dominant.

By extension, these are works in which the magical complexity of possible reactions to a photograph is diminished. There are many treatments of photographs here, but in few of them is the photograph itself the locus of wonder or delight. There is no place, for example, for the deeply non-verbal, almost mystical, religious imagery of the Guatemalan artist Luis González Palma. Nor, at the other end of the scale, is there any room for Enrique Metinides, the “Mexican Weegee”, whose cataloguing of death and disaster was non-judgmental and non-political.

Art in the Americas: eight-page supplement

● Art Basel Miami Beach and the new meaning of Latin America

● Whitechapel at Windsor, Florida: a new show of Jasper Johns

● For the love of bronze (and tin cans): the collection of Janine and J Tomilson Hill

● Miami’s new Pérez Museum opens its doors

Above: Lygia Clark’s ‘Bicho Pássaro do Espaco’ (1960)

The real subject of the exhibition is violence. The start date chosen for the show – 1960 – is not coincidental. The Cuban revolution against Batista took place in 1959, and Cuba has been the yardstick of a certain kind of radicalism ever since. A frightening map showing revolutions and counter-revolutions accompanies the show.

But violence is not only the overt political violence that seems to drive regime change in Latin America. There is also the violence of need, of the favelas and all the rough conditions associated with them. Or the violence of drugs, or of landholding and landowning abuses. Or the violence of race. There are many varieties of violence in Latin America, and even now, as many of its countries show faster growth and greater prosperity than many in Europe or Asia, that violence still seems close to the lives of the people.

Many of the stories told in this show are horrible. Take the series Gloria Evaporada, by Eduardo Villanes, which ironises savagely on the fact that the Peruvian authorities returned the ashes of the victims of the 1992 Cantuta massacre to their families in cardboard boxes which had contained Gloria evaporated milk. You don’t need to speak Spanish to understand the terrible pun. And it is not the pictures which tell the story. A man with his head in a cardboard box labelled Gloria means nothing until we read the facts behind it.

This is a good example of that word-leading element which occurs again and again in this exhibition. The pictures are rarely complete visual communications. They are elements of something else, either powerfully direct like a poster or a headline, or sometimes a more complex amalgam that can only be deciphered with contextual help or a glossary.

It turns out that the Argentine death squads who flew political opponents over the River Plate (during the military dictatorship 1976-83) to dump them alive out at sea consulted ecclesiastical authority to seek confirmation that their method of killing was Christian and non-violent. This is the subject of León Ferrari’s work. It’s madness, the very stuff of a certain kind of art. In the hands of a Zola or a Balzac, it would make a searing novel. It is in literature that such deep traumas of the continent have been most consistently explored, and a catalogue of stories of this kind make up the exhibition. They burn into the mind even in the comfortable surroundings of a contemporary art space in Paris’s 14th arrondissement. Only occasionally, though, are they told in a way rich in photography itself.

A heavily laden family group moves along a pavement in a suburban district. It’s not hard to imagine that everything they own is in their hands. They might be peasants, moving into the city as so many millions have done. We see them through the windshield of a police motorcycle, its lettering clearly legible even in reverse. We have, for a moment, authority’s point of view. A child of the family turns apprehensively; he knows that he is being watched.

This powerful little picture is less of a poster than many of the works in the show; it’s by Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, a highly distinguished photographer, and it really is a photograph, complete within itself. Yet even so, we could not understand it without the seven letters of POLICIA that take up nearly a quarter of the frame.

There’s a ton of thinking and reflection and history in this exhibition, which is thoughtfully divided into four meaty and helpful categories (Territory; The City; Informing/Resisting; and Memory & Identity). Some of the artists are very well known (Francis Alÿs, disappointing here, in a few reworked sketches of some of his walking pieces; Graciela Iturbide, not at all disappointing in her gut-wrenching revelation of the daily torture undergone by Frida Kahlo in the corsets and prostheses she had to wear after a road crash in 1925). Yet the general tenor is rough-and-ready: collage, handwritten messages, stencilling, photocopying. It’s like a huge student show, with the terrible urgency of the issues getting in the way of coolness. But the driving heat is formidably impressive.

It is a very odd thing, this: a photography exhibition in which photography is itself pretty consistently a secondary element. It takes time to see this show, time spent above all reading. But you come out of it profoundly moved by all those artists, raging in pictures.

——————————————-

América Latina 1960-2013, Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, Paris, until April 6 2014

Comments