‘The Great War in Portraits’ at the National Portrait Gallery

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

If Britain had lost the first world war, would the art that emerged from it in this country have been better? The Great War in Portraits, the National Portrait Gallery’s intriguing but uneven new show, does not set out to ask this question, but its most theatrical encounter is between British conservatism and the German avant-garde.

The conclusion is stark: in wartime Berlin and the Weimar Republic, fear and the shock of defeat prompted a radicalism that no British artist between 1916 and 1933 dared risk.

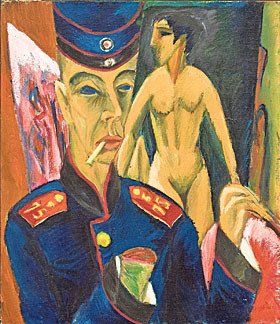

The greatest painting here is Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s “Self-portrait as a Soldier”, loaned from the US and a scintillating example of the nervous, sharp, satirical style that came to characterise Weimar Germany. In acrid, green-tinged flesh tones, Kirchner depicts his face as a primitivist mask with black, hollow eyes staring blankly. He turns away from both a slashed red painting, evocative of a wound, and a nude model waiting for him. He cannot paint her because his right hand is a bloody, gangrened stump.

Yet he has, of course, painted this picture of himself in his studio, wearing the dark blue uniform of the Mansfeld artillery regiment from which he was discharged following a breakdown. His imaginary amputation is symbolic and prophetic – an indictment of war, a herald of the psychological collapse of a nation.

Kirchner had never wanted to fight. His expressionist colleague Max Beckmann was initially more enthusiastic – “For me the war is a miracle, even if a rather uncomfortable one. My art can gorge itself here” – but he too had a nervous breakdown and was invalided out. In the lithograph series “Hell: The Way Home”, on display here, he developed his harsh, jagged, graphic postwar style, chronicling domestic turmoil following military surrender. In a self-portrait as a bony grotesque under a street lamp, he comes face to face with a hideously disfigured veteran amputee: mon semblable, mon frère.

A new visual language here evolves to convey distrust, disillusion, distortion, deformation: what curator Paul Moorhouse calls “a radically altered perception of mankind” in response to the trauma of the world’s first global and mechanised conflict. That trauma determined the course of German 20th-century art, sweeping up in its course even traditionalists such as the belated Prussian impressionist Lovis Corinth, who transformed his style into the agitated melancholy of expressionism, as in a fervent portrait here of his friend, the etcher Hermann Struck, as a weary soldier.

In British art, by contrast, radicalism turned tail. The NPG opens with Jacob Epstein’s truncated Vorticist sculpture “Rock Drill”. Created in 1913, it originally featured a barely human plaster form, his face a helmet, astride a real pneumatic drill – hard, relentless, outrageous in its phallic suggestiveness, a construction that Epstein described as “the armed sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into”: an elision of man and machine.

But in 1916, when the cost of mechanised warfare was clear, Epstein cut off the driller’s legs and hands, transforming him into a fragmented torso, cast in bronze – dismembered, defensive, a symbol of amputation rather than aggression: a revolutionary sculpture tamed.

Among British painters here, formal innovation is only apparent in Christopher Nevinson’s “La Mitrailleuse”, with its soldiers reduced to angular grey planes, fused with their machine guns, the fractured geometric composition asserting the loss of humanity and individuality on the killing fields. Painted in 1915, when Nevinson was a Red Cross orderly, it will, Walter Sickert wrote, “remain the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting”.

Neither Epstein nor Nevinson ever again approached the angry language of these futurist masterpieces. Nevinson, like Kirchner and Beckmann discharged from the army because of illness, returned to the front in 1917 as an official war artist. Now, though, he adopted a conventional realism in works such as “Paths of Glory”, which portrays two dead soldiers in a field of mud and barbed wire, and he dwindled into insignificance after 1918.

The most prominent official war artist was the Irish portraitist William Orpen, who had made a fortune flattering fashionable Edwardian society. Stirred by the fresh challenge – “I have never been so interested in my life” – he delivered sober, sympathetic likenesses, in a vigorous naturalistic style, of army leaders. A dejected Winston Churchill, shoulders bent forward to suggest the weight of regret, broods on his disgrace and resignation as First Lord of the Admiralty after his disastrous Dardanelles campaign. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig looks calm, controlled, but distant, removed from the violence on the front, which is evoked, not described, by background cloudy shapes imitating sky and smoke.

“Why waste your time painting me?” Haig asked Orpen. “Go and paint the men. They’re the fellows who are saving the world, and they’re getting killed every day.”

Little known today, Orpen’s meticulous attempts to capture man and moment are extensively revived here. Intellectually unexciting, they interest primarily as narrative, set in context with other material exploring the range of visual responses to the war from idealised formality – portraits of royalty and generals – to expressions of pain and moral protest.

Many of these are affecting, such as the pastels “Soldiers with Facial Wounds” by Henry Tonks, a reactionary Slade professor who had studied medicine before art, and between 1916 and 1918 provided diagrammatic drawings to surgeon Harold Gillies to assist with facial plastic surgery; accompanying photographs of the servicemen undergoing the reconstructive operations are horrific.

Further snapshots of war’s survivors and victims, famous and obscure, are grouped together as “The Valiant and the Damned” and include an unidentified Gurkha, an anonymous downcast German prisoner, flying ace Baron von Richthofen, and stony-faced Maria Bochkareva, a peasant who formed the 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death and was shot dead by the Bolsheviks.

As often at the National Portrait Gallery, this show struggles between two imperatives: documentary and aesthetic. Its competing strands – anecdotal accounts of individual wartime experiences on the one hand, the story of war’s impact on great painting on the other – never mesh. There are marvellous high points, yet the selection of works feels random; the exhibition provokes, yet fails to cohere conceptually or visually.

By the end, I wondered if that confusion was maybe the point: this war which determined 20th-century history was always too shocking and too complex for its participants to understand. The exhibition’s poster image is Orpen’s self-portrait as a bewildered figure huddled in scarf, helmet and trenchcoat, drawing with a gloved hand. While painting it, he wrote, “I work and work, but I don’t expect anything I do will be any good or is any good – the whole thing is so vast . . . ”

——————————————-

‘The Great War in Portraits’, National Portrait Gallery, London, to June 15, npg.org.uk

Comments