The Diary: Simon Sebag Montefiore

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I’ve just spent weeks in Istanbul filming a TV series on its history. It’s amazing how being in the tombs, cisterns and tunnels of fallen empires makes one voraciously hungry for the present. At night, emerging from the sarcophagi of caesars and sultans, I embraced the deliciously cosmopolitan glamour of the modern megalopolis – cafés in Galata, speedboats rearing across the darkened Bosphorus, seafood restaurants in teeming fish markets.

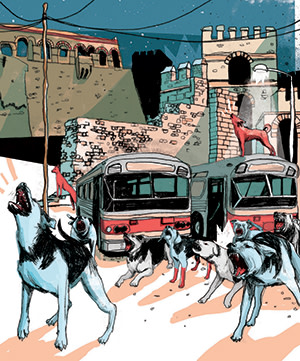

One of the joys of filming in Istanbul is finding the neglected jewels and forgotten places that tell the real secret life of a city. Many of the ancient Theodosian walls still survive, though far from the tourist routes, and we excitedly make our way there to find a twilight netherworld of shanty hovels, tramps and graveyards for old buses. Under the ancient arches, there is also a pound for abandoned dogs, from where hundreds of snarling, barefanged mongrels are howling. While we nervously debate whether or not to film there, the dogs make up our minds for us. Leaping out of arches, shacks and old buses, they form a pack and approach, growling, then suddenly give chase. In a terrifying scene, a cross between Mad Max, Cujo and 101 Dalmatians, I contemplate rabies or being torn apart and eaten. We just make it back to our van.

. . .

The most thrilling place we explored was a vast underground structure beneath the Hippodrome, the circus that lay at the centre of life in Constantinople. The stadium itself is long gone but this huge circular building can only be entered through a tiny locked door, has never been opened to the public and only rarely been filmed. Yet this place, the Sphendone, was where horses and charioteers were marshalled before they galloped up into the Hippodrome to race and die before the baying crowds.

Programme-makers seem to specialise in making me perform filthy and fearsome exploits underground, which I manfully try to resist. In Rome last year it was scaling down into the ancient sewers, the Cloaca Maxima, where I certainly experienced the stink of history. I had a tantrum but finally agreed to do it. Now this!

I enter the building fearfully. It is pitch-dark, muddy and rough. Pillars are crumbling, and off to every side are long dark galleries. I point my torch into the gloom. Suddenly we all freeze: a huge wild dog stands there staring at us with eyes like Cerberus’s, I break out into a sweat but it curls up, whines and then dies right there in this macabre place. Through the niches I see halls so big I can’t make out the bottom. I come to a doorway leading into a terrifying void. There are old steps with no banister between me and a gaping drop. Clinging to the wall, I creep down into this apparently bottomless space and finally discovers it’s filled with water. A flotilla of bats flutters round squealing, giving me such a shock I almost fall off, rats slither out of the water and pigeons beat the air with their wings high above. Finally I reach the bottom.

It was here, too, that in 695 the deposed Emperor Justinian II, one of the more grotesque heroes of my series, had his nose cut off and tongue amputated to prevent him ever reigning again – the now-forgotten punishments of rhinokopia and elinguation were gruesome rituals in the blend of vicious politics and silky ritual we still call “Byzantine”. But, like the villain of a horror film, Emperor Slitnose returned, wearing a bejewelled golden nose-mask, accompanied by a special translator to interpret his tyrannical tongueless gruntings. His reign of terror ended in 711 with his second fall: this time he lost more than his nose.

. . .

On Republic Day in modern Istanbul, there were photographs of Atatürk everywhere. Apart from his Valentino-esque matinee idol looks, I was struck by the sartorial splendour of Turkey’s first president: he seems never to have worn the same suit twice, appearing in everything from tweeds, pinstripes and knickerbockers to spats, tails and white flannels – and headwear including fezes, homburgs, trilbies, peaked caps and top hats.

Following the Taksim Square protests this year, the BBC was nervous about us being caught up in any demonstrations: when our director called the office on a bad line to check how many people had been killed in the Nika riots, the researcher in Manchester misheard, thought we were trapped in a murderous uprising and pressed the emergency button, calling the BBC’s security specialists to get us out. When we called back, we had to explain that the riots in question were 1,500 years ago.

. . .

My new novel, One Night in Winter, is a thriller-cum-love story based on a true case in the Russia of Stalin, who with his taste for gigantic projects and sporty spectaculars, would have approved of the country’s imminent Winter Olympics. He also loved Sochi, though given the ambiguous status of Stalin in Putinist Russia – he swings between respected Red Tsar and unmentionable monster – will visitors to the games be allowed to visit the house that made Sochi, at times, the secret capital of the Soviet empire?

After the war, Stalin spent months here each year, holidaying in this two-storey mansion, painted a grim camouflage green. Until the Olympics, it was Sochi’s main attraction; tourists could see Stalin’s camp bed, the desk with inkwells, his bulletproof sofa, swimming pool and billiard-room-cum-cinema – a feature of all his residences. Eerily, a life-sized waxwork of Stalin, uniformed and booted, sits behind the desk. I hope he’ll be taken out to watch the slalom.

——————————————-

The final part of ‘Byzantium: A Tale of Three Cities’ is on BBC4 on Thursday. ‘One Night in Winter’ (Century, RRP£16.99) is out now

Comments