The grant that recognises the value of museums

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Each year since 2012, the Tefaf Museum Restoration Fund has awarded €50,000 in grants to international museums for conservation and research projects. This year, the money goes to two institutions — London’s Victoria & Albert Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

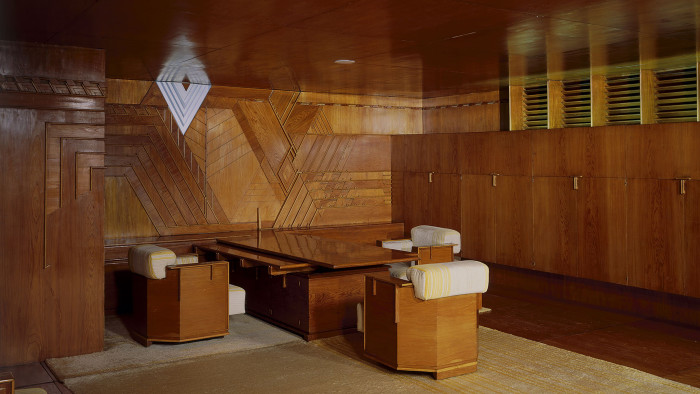

In London, the V&A is undertaking the restoration of an interior by the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959). LACMA is undertaking the conservation of a recently acquired “Pietá” by Melchor Pérez Holguín (c1660-c1732), the most important Bolivian painter of the Spanish colonial period.

The diversity of the grants show something of the fund’s intentions: they try to spread the awards around different disciplines. Past projects include the 2014 Egyptian coffin project, which focused on coffins and mummy boards in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (National Museum of Antiquities), Leiden; the 2017 project to restore “Judith with the Head of Holofernes” (c1570) by Titian at the Detroit Institute of Arts; and the 2018 project to restore the baroque Capula das Albertas of the Order of the Discalced Carmelites, now part of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon.

Since its beginnings 32 years ago, Tefaf has attracted directors and curators from the world’s top museums looking to buy for their collections. The Restoration Fund, provided by the fair’s organising non-profit body, the European Fine Art Foundation, is a way of recognising museums’ value as clients and the scholarship that they provide to the art trade.

Institutions are invited to present projects to an independent panel of judges, currently comprising a dealer, a former museum director and three conservators or scientists. So far only Europeans and Americans have applied — this year there were 21 — but the panel’s chair, Rachel Kaminsky, says she hopes for applications from Asia and Africa.

This year’s winning projects are both, in their different ways, transformative. The Kaufmann Office has been in store for most of the time since it was presented to the V&A museum by Edgar J. Kaufmann, Jr in 1974, but when cleaning and remedial work is complete it will be one of the highlights of the new V&A East in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. The office is the most complete and original Wright interior to survive outside America. The commission was completed in 1937, and together with one of Wright’s most famous buildings, Fallingwater (for Kaufmann Sr, his patron) revived the architect’s career after the Great Depression.

Kaufmann (1885-1955) owned the principal department store in Pittsburgh, a monumental classical building by Benno Janssen, where his original office was furnished “like an old country house in Normandy”. His son, an aspiring artist and architect who had been a paying apprentice with Wright, persuaded him to commission a much more daring design for a new office.

This L-shaped room occupied a glass-windowed corner of the building’s 10th floor, and every detail was designed by Wright. It is a paean to plywood. Swamp cypress plywood is employed for the interior walls, floor, ceiling and furniture, and the light from the two exterior sides was filtered through louvres, also plywood. The room is 8ft high, and the ceiling, walls and floor are constructed of 4ft square panels, the measurements dictated by the US standard dimensions for plywood sheets.

Wright insisted that decoration should be integral to surfaces, and thus the main feature is an Art Deco-like geometric mural composed of strips of the same swamp cypress, incorporating a triangular light fixture set flush to the wood. Below is a shelf which extends to form the top of the desk. This desk consists of two overlapping surfaces that cantilever into the room like Fallingwater over its waterfall. Rugs and fabrics for seat coverings were by Wright together with Loja Saarinen.

After his father’s death, Kaufmann Jr wrote to Sir John Pope-Hennessy, then Director of the V&A, in November 1973, about the planned gift: “May I say that I am very proud, as well as pleased, that this good example of Wright’s mature art will be visible in Europe under the aegis of the institution that led the scholarly and popular revaluations of the arts of design . . . Wright’s work could not have found a safer or a more suitable haven.”

Yet the office did not achieve a settled home in the public gaze. It was displayed in the museum’s main entrance for several months before being placed in store, and not shown again until 1990 when, on loan to Japan, it was seen by over 150,000 people. Back in London, it was installed in the V&A’s Henry Cole Wing, but remained on view only until 2005. It has survived its travels surprisingly well; as Christopher Wilk, Keeper of Furniture at the museum and biographer of Wright, points out: “plywood is remarkably durable.” At V&A East, the installation will be permanently on view for the first time.

The grant to LACMA should prove equally significant. For the last 15 years, the museum has been building a collection of South American art from the Spanish colonial period, and the Holguín is the first work by a Bolivian to be acquired. Ilona Katzew, head of Latin American art, has said that when the painting was offered to her last year, she was astounded by its power. It had obvious conservation problems, notably “its abraded surface, yellowing varnish, some minor paint losses, and its need for cleaning and the integration of the various pictorial elements. Knowing that this would be an extraordinary project for our team of conservators, I persuaded the vendor to sell us the picture ‘as is’.”

Although Holguín is recognised as one of the most distinct artistic personalities from the colonial period in South America, little is known about his painting methods. Thanks to the Tefaf grant, a thorough scientific analysis and restoration will be undertaken, which should produce valuable information about Holguín’s technique, use of pigments and pictorial choices.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our culture podcast, Culture Call, where editors Gris and Lilah dig into the trends shaping life in the 2020s, interview the people breaking new ground and bring you behind the scenes of FT Life & Arts journalism. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Comments