Is the future of car insurance at risk from fewer accidents?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A city-dweller stepping into the street to wave down a taxi is becoming a rarer sight, as ride-hailing platforms like Uber proliferate. But seeing a driver with their hands on the wheel may also become the exception.

Visions of driverless taxis roaming the streets took a step forward in April when Tesla’s chief executive Elon Musk said that he expected to launch such a fleet by the end of next year. The question of how these vehicles will be insured is, however, still up in the air.

The immediate problems are more financial than legal. The growth of technology in cars is creating a headache for insurance companies, which are finding that repairs are becoming more expensive.

According to claims data from US-based insurer Travelers, the cost of repairing the 2018 model of one popular sedan is up to three times higher than the 2017 model, because of collision avoidance technology in the newer model’s front grill and bumper.

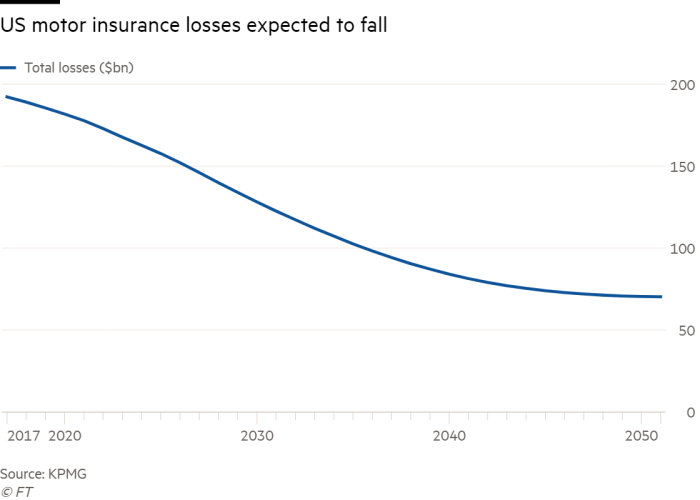

But over time, the rising cost of each repair should be more than offset by a lower number of accidents as cars become safer. KPMG has predicted that, in the US, total losses from auto accidents could decline by 63 per cent by 2050, wiping $122bn off the cost of claims.

This could present a long-term challenge to insurers: a structural decline in claims could feed through into lower premiums that they could charge.

Michael Klein, president of personal insurance at Travelers, says it is too early to say for sure whether accidents are becoming less common. “Commentary over the past six to 12 months suggests that improvements in safety features are starting to have an impact on frequency, but at the moment it is very hard to prove.”

There have been similar trends in other industries. “The parallel is aviation,” says Lex Baugh, chief executive of North America general insurance at AIG. “Automation has made air travel safer, so insurance premiums have been on a long-term decline in that sector. As auto catches up, we anticipate a safety dividend.”

Another fundamental question is who should have to pay the bill — and hence who should buy the insurance — when semi-autonomous or fully-autonomous vehicles are involved in accidents.

At the moment, insurance is bought by the owner or operator of a vehicle. Around the world, car insurance tends to be a personal policy because most accidents are caused by drivers.

When it comes to autonomous vehicles, that might change. “If we are talking about a car where something is wrong, the producer of the vehicle would be liable,” says Professor James Davey of the University of Southampton. “These look like product liability issues to me.”

That would change the nature of vehicle insurance. Rather than a personal policy, it would be a commercial product that manufacturers would have to buy. That could pose a bigger threat to the companies that specialise in selling personal vehicle insurance today.

Some insurance executives argue that it would be a mistake to turn vehicle insurance into a product liability. Mr Klein says that traditional personal policies will still be a far better way to protect vehicles, their drivers and third parties who might be involved in a collision.

“We think the existing mechanism is the most able to respond . . . If you look at product liability as the primary mechanism, it is not designed to respond to a situation where accidents are so frequent,” he says.

He argues that the roads will be filled with a mixture of autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles for years to come and that only traditional insurance will be able to deal with all the possible incidents that could arise.

Karl Gray, global head of motor and retail lines at insurer Zurich, says that governments and regulators agree with the industry’s stance. “[They] want a continuation of traditional insurance — they don’t want a situation where a third party cannot make a claim quickly.

“They want a primary insurer to cover the vehicle, and that insurer could then pursue a claim against the manufacturer.”

But not all insurers think that the current set-up can survive. Mr Baugh at AIG believes that insurance will have to evolve to deal with both autonomous vehicles and new ownership models such as car clubs.

“Responsibility may be better suited with the manufacturer or the provider of the transport,” he says. “We need to innovate to a different kind of solution — I don’t think you can think about it in terms of the sort of policies that are available today.”

It is not just the question of liability that needs to be resolved. Insurers also point out that access to data will be increasingly important when vehicles are on the roads. They are worried that, in some circumstances, they might not be able to get hold of the information they need.

“The data will be required to price the vehicle properly,” said Mr Gray. “Insurers that aren’t using the data will be at a disadvantage. It is crucial that insurers have access to the data.”

Mr Baugh says that it is important that lawmakers get to grips with all of the challenges: “The more clarity we can create from a legislative standpoint, the easier it is going to be for all parties. The struggle we have at the moment is that it is not even clear how the technology will be deployed.”

Comments