Jasper Johns: ‘Regrets belong to everybody, don’t they?’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

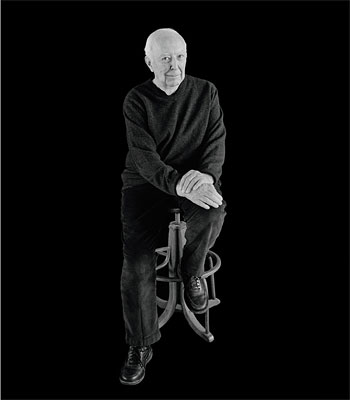

On a bright but raw January day in Sharon, Connecticut, Jasper Johns turns the ignition key in his green Gator golf cart, enclosed in Plexiglas for the winter. Nothing. “Frozen again,” he says in his deep, commanding voice. We climb out and, rather than trudging through the snow, drive a car from the Coach Barn, which houses his painting and printmaking studios, a short distance on his sprawling estate to the Blue Barn. Before he converted it into an elegant private gallery a couple of years ago so he wouldn’t have to upend his studios every time a curator came by for a look-see, the barn sheltered his collection of guinea fowl. The birds, he explains, had “disappeared. One was run over. A few were eaten by fox or coyote or whatever we have up here.” They’re particularly stupid, in his view, but he was fond of them nonetheless. “They made horrible sounds, which I love. They were beautiful birds.”

Today the serene views of New England hills gleaming white under a fresh coat of snow contrast sharply with the artworks lining the gallery walls: paintings and works on paper, predominantly in greys and blacks, all riffing on the same image of a man sitting, with one leg tucked under him, on an old-fashioned iron bed, clutching his head in his hand as if in despair. If there were any question as to the mental anguish portrayed here, Johns has stamped an emphatic “Regrets, Jasper Johns” on each piece. The series, the latest from the renowned but elusive artist, is also titled “Regrets”.

There is an introspective poignancy to the work, a declarative statement in the artist’s late period – he turns 84 in May. It may be viewed as a window to the artist’s own state of mind, a vigorous confrontation with the waning of life by a virtuoso painter and draughtsman. The impact is potent enough that when two curators from the Museum of Modern Art paid separate studio visits last summer, they both proposed putting it directly into a solo exhibition at the museum, bypassing the typical introductory show at Matthew Marks Gallery. “I hadn’t planned a showing,” says Johns, who has led me to a pair of black leather chairs in another room, opposite an enormous Bruce Nauman sculpture hanging from the ceiling. “I was just making new work.”

“Regrets” will have its public debut at MoMA on March 15 and is likely to spark the kind of debate that has long engulfed Johns. Since his breakthrough first solo show, at the Castelli Gallery in 1958, when he put forth a nervy rebuke to the ubiquitous Abstract Expressionism, he has never failed to command the art world’s attention, even when his idiosyncratic iconography felt to some like a wild-goose chase. These latest works hold enough potential allusions to a web of art world names – late great masters Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, one-time Johns intimate and peer Robert Rauschenberg, and Johns’ erstwhile assistant James Meyer – to keep postgrad students mired in dissertations for years to come.

Silver-haired, with rosy cheeks, Johns has perfected the trick of being simultaneously dour and disarmingly self-deprecating. Asked if he reads art criticism about himself, he replies with a subtle smile, “Has there been any lately?” Notoriously laconic, he is circumspect about any autobiographical component to “Regrets”; he has always subscribed to the Duchampian notion that viewers should complete an artwork by bringing their own meaning. Still, it is impossible to ignore the starting point for the series: early 2012, not long after he learnt that Meyer, who had served as his studio assistant for 27 years, had allegedly been stealing unfinished works and covertly selling them through a New York gallery. Johns was reportedly shaken by the betrayal. “Certainly not a pleasure,” he says of the ordeal. “But I can’t talk about it. I don’t want to talk about it. I don’t want to define it in any way.”

He is cagey about the new artworks’ connection to Meyer: “For me [the meaning] is within the picture. The word is in the picture. I think you’ll have to interpret that for yourself. It’s certainly in the painting, but so is the rest of the painting in the painting, and the image that’s in the painting. It’s not meant to be a sign of something not in the painting. Regrets belong to everybody, don’t they?”

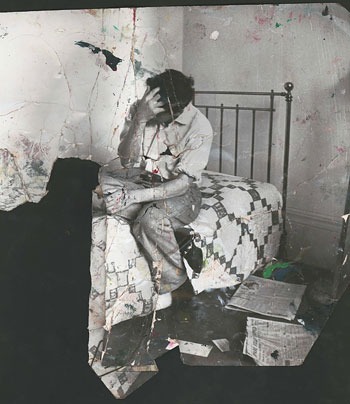

Johns began “Regrets” after he came across an old photograph in a 2012 auction catalogue from Christie’s, London – though he seems little concerned with the image’s context or provenance. “It was a sale of – who’s the other artist? Francis Bacon.” On the block was Bacon’s “Study for Self-Portrait” (1964) and the catalogue had published the source material, a portfolio of photographs found in Bacon’s studio after his death in 1992. Taken by the photographer John Deakin, the pictures were of Bacon’s friend and fellow artist Lucian Freud. Bacon had married Freud’s body with his own face in “Self-Portrait”. “This is the one that struck me,” Johns says, pointing to the image of Freud perched on the quilt-covered bed and hiding his face in his hand, newspapers at his feet. The photograph was paint-splattered and torn, with a large chunk of the lower left side missing altogether, and the creases and voids – the photograph as object – were as interesting to Johns as the image itself. “Bacon mistreated the photographs physically, is what it looks like,” Johns says. “I just saw that and it caught my eye.”

He began toying with the page from the catalogue almost immediately, ripping it out, tracing the silhouette, then copying that drawing on a photocopier. After filling in the space with coloured pencil, he glued it to a larger sheet of paper, making an abstract watercolour opposite the drawing. Explaining the reasons behind his methodology is difficult for him. “I saw it and wanted to do something,” he says, taking a sip of tea. “I don’t know how you go from there. You start thinking.”

The way he makes it sound, the faint stamp of “Regrets” in the upper right corner was almost a lark. He ordered the rubber stamp of his own handwriting years ago to use as an ironic reply to autograph-seekers, among others – invoking the word’s other meaning, polite refusal. “When people ask me to do things I don’t want to do, I stamp that,” he says with a big smile. “I don’t use it very often, but occasionally.”

He’d never before used it to make an artwork. Why now? “Well, it was right there in front of me,” near the copy machine, he says. “I assume I associated it with the image of [Freud].” On another drawing Johns wrote in pencil at the bottom, “Goya? Bats? Dreams?” The words are not a title, he says, “just notes of mine, association”.

It may be simply another coincidence that Bacon and Freud were once close friends but had a bitter break, mirroring the rupture between Johns and Rauschenberg more than half a century ago. Johns, though, insists any similarity is accidental. “I don’t know anything about their lives, so that wouldn’t be important to me,” he says.

Johns also claims never to have met either artist, though his friend Bill Katz, who was also close to Bacon (and who renovated the barns and Johns’ grand, stone house), recalls with a chuckle, “I remember introducing [Bacon and Johns] at lunch. When I tell Jasper things he thinks he doesn’t remember, he says, ‘Interesting if true’.”

Though Johns owns a small Freud painting, “a portrait of a poet”, he denies especially admiring either artist. “I don’t think it had anything to do with either of them,” he says before allowing, “You don’t know what happens in your unconscious.”

While Johns tends to lay plenty on his subconscious – an amusing irony in this case, considering Lucian’s grandfather was Sigmund – his long-time print collaborator Bill Goldston advises, “Jasper never does anything idly. There’s nothing in his work that isn’t considered.” Goldston, at Johns’ behest, made silkscreens of the “Regrets” stamp, complete with the artist’s written instruction, “Enlarge,” which also appears in the works. Though they have worked together for more than 40 years, Goldston knows better than to assume he comprehends the meaning behind Johns’ gestures. “It’s impossible to understand his motivation,” he says. “How can you possibly understand what he was thinking about Bacon in relation to Freud? I’m still working on the image and trying to understand how it’s broken up. The real fun is looking at the work and getting what you get.”

Whether rubbing and making lines with charcoal, painting with watercolour and dabbing pastel on heavily textured paper, or using India ink on mylar (polyester film) for a set of four drawings that break up the image in varying degrees, Johns offers a masterclass in technique. Despite the same starting point, each work is emphatically unique, a tour de force of experimentation. One of the paintings – in oil, not his signature encaustic made of pigmented hot wax – obscures Freud in a brooding palette of greys; in another, Freud is a jigsaw of cascading red, blue and yellow against a grey backdrop. Next to him, he outlined a small empty rectangle. Asked what it’s doing there, Johns shrugs his shoulders, smiles and takes a bite of a cookie. For all the influence he has wielded in contemporary art, he is also known, quite simply, as a first-rate paint handler. But Johns isn’t so sure. “I think it’s something I don’t know how to do,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t know what my limitations are and what the opposites of that are. I don’t know what my virtues and faults are.”

Showing the series in full, says Ann Temkin, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, opens a window to Johns’ creative process. “[It] gives viewers the opportunity to feel you are there in the studio and in the artist’s imagination,” she says. “He seems to have an urgency, which is thrilling to encounter. It’s very palpable when you look at these.”

Many of the works play with mirror images of the Freud portrait. “I don’t know why I decided to double it,” Johns says. “It’s curious because there’s one with it doubled one on top of the other – a completely different use of space. The others [opposite each other], I found it interesting – the forms, the negative space where he’d torn the picture.” Where the twin images adjoin, they form a skull, a reference to mortality that Johns claims is accidental.

…

As with most people who make it to their mid-eighties, many of Johns’ close friends from his formative years have died: the radical composer John Cage and his partner, the equally inventive choreographer Merce Cunningham; Leo Castelli, Johns’ dealer of 40 years; and Rauschenberg, the artist with whom Johns is inextricably linked. Together, the group formed a hub of creativity in the New York of the 1950s.

Johns had endured an epically painful childhood bouncing from one relative to another in South Carolina. “It had no stability at all,” he says. After his parents divorced when he was two, he was sent to his paternal grandfather. When I inquire if he grew up on a farm, Johns inexplicably laughs uproariously. “My grandfather didn’t live on a farm,” he says. “He had farms. He lived in town.” The farms, plural, were still set up like antebellum plantations, Johns recalls, each with a big house and a group of small structures where the black labourers lived. “I assume they had been slave quarters,” he says. “My best friend was a black boy who was the son of my grandfather’s overseer. That family lived in town, only about a block or two away from our house. His mother, I think, did our laundry.”

The disparities of the racially segregated South seeped into his consciousness over time. “I have one odd memory: we had a cook, a black woman named Donie, and I remember one afternoon going home with her to her house,” Johns recalls. “Donie made a cake when we got there, a coarse cake. When it was out of the oven, she cut it, gave me a piece. She had two children, and she gave them [a piece]. When I finished I asked for another piece. She said no, she had made it for her children; I had so much at home and she wasn’t going to give her children’s cake to me.” At the time, he felt wounded, since “she was somebody I trusted with my wellbeing. Only later I saw how touching her feelings were.”

When Johns was in third grade, his grandfather died. Johns stayed briefly with his mother and her new family before being sent to his paternal aunt, a schoolteacher who taught in a “two-room schoolhouse, but only one room was used. There were 12 to 13 children at most.” In high school he returned to his mother yet again.

In 1949, when he was 19, Johns dropped out of the University of South Carolina to move to New York, where he tried studying commercial art at Parsons School of Design. “When I came to New York, I was not adventurous. I had a kind of formless existence of always wanting to be an artist, but I had not much training,” he says. “I had no contact with people who were artists. That’s why meeting Bob Rauschenberg and John Cage and Merce Cunningham was so important to me. In my past I had no artists.”

He and Rauschenberg became exceptionally close, taking studios in the same building, making money by designing window displays together for Tiffany’s, and pushing one another artistically. They are frequently described as lovers. As recently as 2013, some critics scorned them – and MoMA, on the occasion of its show, “Johns and Rauschenberg” – for not being blunt about the nature of their relationship. When I asked him several years ago if he and Rauschenberg had been romantically involved, he retorted, “How is it relevant?” For Johns, who once said that while growing up he always felt like a guest in someone else’s house, what mattered was that he’d finally found “kin”.

It was one night during that period in the 1950s that Johns dreamt he was painting a flag. That dream led to “Flag”, a seminal painting of the Stars and Stripes that conflated image and object: was it a flag or a representation of a flag? Looking back, Johns isn’t sure if he realised how radical the piece was in the scope of contemporary art. “It was radical for me,” he says. “I had no interest or knowledge of what I was doing relative to anything else.” “Flag” helped confirm in his own mind that he was an artist. He destroyed his earlier work. “I did lots of other stuff, but it was done in a different spirit. It was done with the spirit that I wanted to be an artist, not that I was an artist.”

Next came paintings of other universally recognised symbols: targets, numbers, letters and, later, maps. One day when Castelli was visiting Rauschenberg, he saw Johns’ work and offered him a show then and there. It was an auspicious debut: MoMA bought an astounding three pieces. “For me it was unbelievable,” Johns recalls. “It was my first experience having a show. It was my first contact with people important in the art world.” Alfred Barr, MoMA’s influential first director, made the selections himself. “Alfred thought they might not last very long the way they were made” – with ephemeral materials such as newspaper encrusted in the paint – “but then he said something like, ‘We might not last very long either.’”

In 1961, after seven years, Johns and Rauschenberg had a falling out. Even after all this time, Johns does not have a neat explanation as to why. “I wonder if I know,” he says, before adding for good measure, “But I certainly don’t want to talk about it if I do.” He stretches in his chair, clasping his hands behind his head and crossing his legs at the ankles, defiantly silent.

Their split has repeatedly been described as bitter and total, with critics speculating that Johns’ painting “Liar”, for instance, was in reference to Rauschenberg. But Johns’ version of the aftermath is less dramatic. “Bob and I were not unfriendly,” he says. Neither were they friendly – he told me nine years ago that they saw each other “only by chance”. Perhaps they both mellowed with age. Johns did attend Rauschenberg’s memorial service in 2008. “Myths develop. I think people make things up,” he says. “There’s nothing I want to set straight about the record.” When he chooses to reveal something, one friend says, it’s in his art.

…

Johns retreated from New York to bucolic Sharon in the 1990s. Meyer, a painter whom Johns had hired in 1985 after he knocked on the door of Johns’ Manhattan studio, moved to the nearby town of Salisbury where he lived with his family. Sometime between 2006 and 2012, according to an indictment handed down last August, Meyer allegedly removed at least 22 unfinished artworks from Johns’ studio, where he was responsible for their safekeeping, and transported them to New York, where he sold them through an unnamed gallery, falsely claiming they were gifts. To prove their authenticity, he allegedly went so far as to create fictitious inventory numbers and produce fake pages for Johns’ ledger of completed artworks. The gallery sold the works for roughly $6.5m, $3.4m of which allegedly went to Meyer. If convicted of interstate transport of stolen property and wire fraud, Meyer could be sentenced to a maximum of 30 years in prison. Neither Meyer nor his lawyer responded to requests for comment. While friends of Johns say he was devastated by the alleged deception – one likens it to his parents’ virtual abandonment of him – they also hesitate to draw a straight line from the incident to “Regrets”, calling this too linear for such a complicated man.

For decades Johns also spent a good deal of time at his house on the Caribbean island of St Martin, but he has mostly stayed in Connecticut for the past few winters. “For some reason, the last time I worked there and finished something, I cleaned out the studio,” he says. “The only reason to go is to sit in the sunshine for a few days. That’s not very interesting to me.” He’s comfortable here, in the big stone house.

Even after 60 years of making art, though, Johns is still not entirely at ease with his practice. “I laboured over these a lot,” he says of “Regrets”. “Somehow what you end up with seems to be something you should have known was there to begin with, even though you had to work so hard to find it.”

That being an artist is still so arduous perplexes him. “I worry about the difficulty of making things, or the difficulty of knowing what to do,” he admits. “I may think, having been working at this all these years, why don’t I find it easy? Since it’s a relatively simple activity.”

——————————————-

‘Jasper Johns, Regrets’ opens at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, on March 15

To comment on this article, please email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments