Trend-following hedge funds struggle in topsy turvy year

Simply sign up to the Hedge funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

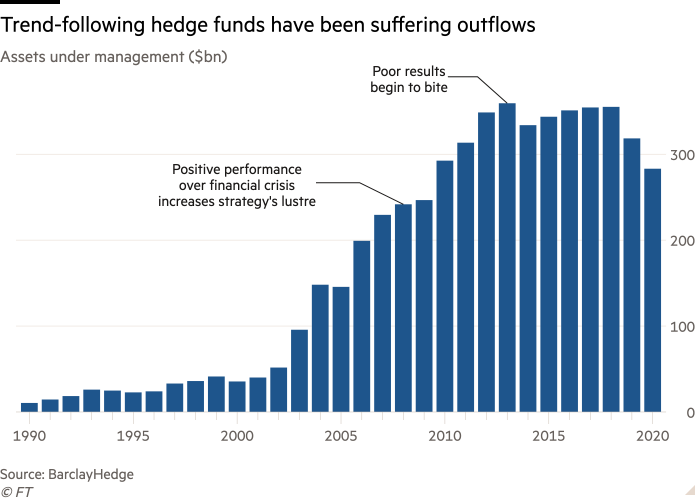

Savage stock market drops, soaring rallies and a frenzied retail trading boom. This should be a fertile environment for quantitative trend-following hedge funds. Instead, the $280bn industry has experienced widely diverging fortunes this year.

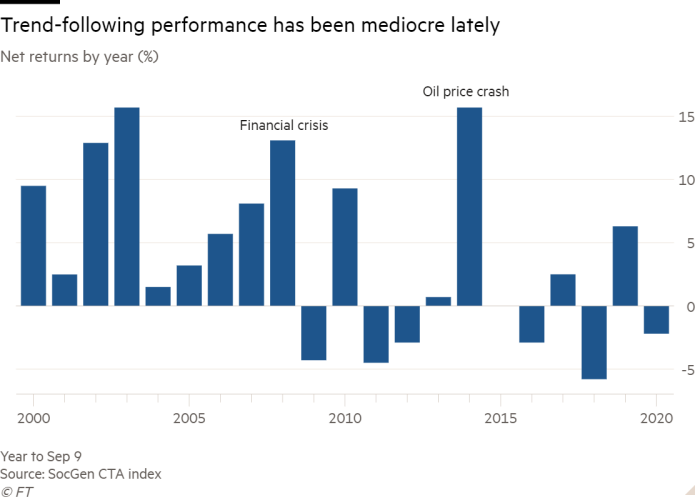

Société Générale’s index of commodity-trading advisers — a common regulatory designation for “quant” funds that specialise in riding market trends — is down 2.2 per cent this year. That is below the hedge fund industry’s average 2 per cent gain, according to HFR, and masks some stark differences between trend-followers.

This year has been a “crucible” for CTAs, according to Edward Raymond, head of UK portfolio management at Julius Baer. “It’s the anatomy of the downturn that matters,” he said. “Some did well and others did not, and we’ve seen a wide dispersion of performance this year.”

Aspect Capital, Millburn and Winton Group are down about 7 per cent, 12 per cent and 17 per cent respectively, according to numbers sent to investors and seen by the FT.

In contrast, Roy Niederhoffer’s Diversified Fund and the Tewksbury Investment Fund have gained roughly 44 per cent and 18 per cent. Man AHL’s trend funds are up 3 to 4 per cent, while other big players — such as AQR — have trodden water.

The disparity is partly explained by the swiftness and depth of the market drop and then recovery, as trend-followers naturally suffer to some degree in abrupt changes in market momentum.

Yet two factors have also stuck out: whether they branched out into other quant trading strategies, and whether funds reacted quickly to market moves or looked at longer-term patterns.

Although many hedge funds have been rattled this year, the performance of trend-followers is of particular importance. Since the financial crisis they have become popular among many pension funds, private banks and endowments as a kind of insurance policy against downturns — thanks to previous strong performances at times of turmoil, such as in 2008. Understanding the reasons for the mixed results of 2020 is therefore vital for many institutional investors.

“There’s always some dispersion in the industry, but there’s certainly an unusual amount of it this year,” said Sushil Wadhwani, the chief investment officer of QMA Wadhwani, a hedge fund group.

This is quite a shift from 2008, when most trend-following hedge funds profited from massive, sustained falls in stocks and oil, and a bond rally. The main differentiator was just how well they did. The SocGen CTA index climbed 13 per cent the year the financial crisis wracked markets.

But the aftermath was tougher. “Life began to get more difficult for us and all trend-followers when interest rates went to zero and volatility fell,” said David Gorton of DG Partners, which runs a trend-following fund in a joint venture with Brevan Howard, that is up 5.4 per cent this year.

The poor run meant some trend-followers started drifting from their core strategy in recent years, dabbling with new signals and techniques, according to Mr Gorton. That cost them when traditional trend-following enjoyed a renaissance and many other strategies struggled this year, he argued.

An example of the cost of this strategy drift is the woes of Winton, once one of the highest-profile trend-following hedge funds, which publicly shifted into other techniques such as trading based on macroeconomic data.

This year Winton’s main fund is down 17 per cent, while its smaller, purer trend-following fund is up about 3 per cent. “The things we’ve diversified into have done worse than trend-following. But I don’t necessarily think it shows I got it wrong,” said David Harding, Winton’s founder.

Some industry executives disagreed that adding alternative strategies has led to weak performance. Mr Wadhwani said his company has benefited hugely from non-trend strategies, such as incorporating a heavy dose of “macro” investing, through quicker and more accurate forecasts of economic growth and inflation rates. “It’s really what saved our fund” in the lean years, he said. QMAW’s Trend Plus Strategy is up 5.4 per cent this year.

Leda Braga, the head of Systematica — whose BlueTrend fund is up about 5 per cent this year — reckons a drift away from trend-following is likely a reason behind at least some of the muddled performance of many CTAs this year. But she argued that whether managers looked at market patterns over short or long time periods is also a major differentiator.

Inside ETFs

The FT has teamed up with ETF specialist TrackInsight to bring you independent and reliable data alongside our essential news and analysis of everything from market trends and new issues, to risk management and advice on constructing your portfolio. Find out more here

Most CTAs typically use strategies that last a few months. While some might only hold positions for a few days, this is territory that has become less profitable and dominated by other higher-speed hedge funds and market-makers.

Yet these faster-changing strategies usually “work well with a rapid fall in markets,” such as in 2020, said Sandy Rattray, chief investment officer at Man Group, which manages $108bn in assets.

This year’s volatile conditions underscore the need to continually improve on trend-following systems rather than drifting too far from the core strategy, according to Ms Braga.

“We don’t claim to have found the Holy Grail. We have to continually learn and adapt our algorithms to cope better, enrich our models and prepare them for regime changes,” she said.

Twitter: @robinwigg

Comments